“Do you mind if we swing by the Starbucks drive-through before we go to the cemetery?” Bethany Cosentino asks, steering her Subaru into a wide Los Angeles intersection. “I’m a real chain girl, sorry.” She’s planned an afternoon field trip to Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, one of the city’s most iconic resting places for celebrities (Clark Gable, Michael Jackson, Elizabeth Taylor), captains of industry, and some 250,000 lesser-known Angelenos. But first, caffeine.

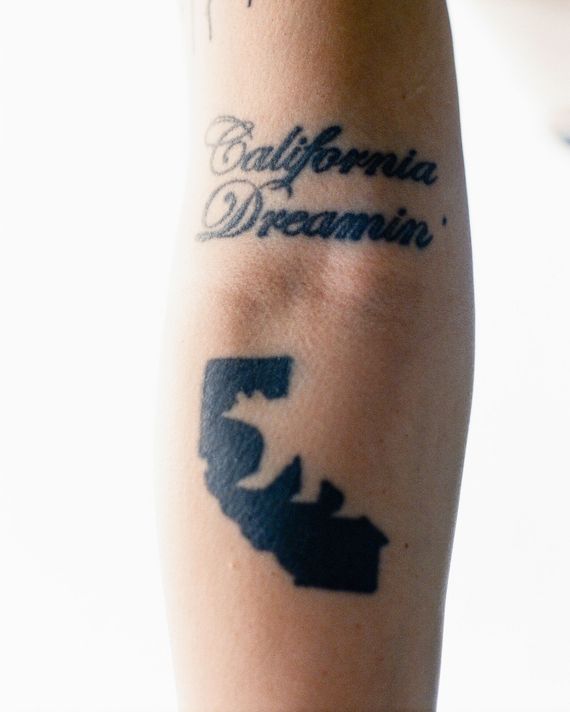

A deadpan, Ray-Banned queen of the mid-aughts indie scene who spent more than a decade with the sunny slack-rock duo Best Coast, Cosentino is probably still best known, she admits, as the “lazy, crazy baby who loves her cat and palm trees and weed.” By 26, she had landed on the cover of Spin magazine with then-boyfriend Nathan Williams of Wavves, opened stadium tours for Weezer and Green Day, and become a tattooed avatar of next-wave millennial feminism. In an age when a certain kind of casual bloggerati misogyny thrived, she also proved consistently unafraid of engaging onstage and online. (Those years of enduring tired girl-with-guitar critiques and an industry that all but sanctioned male sexual misbehavior culminated in a watershed 2017 op-ed for Billboard.)

Around the time of the band’s fourth album, 2020’s Always Tomorrow, though, the singer got sober and started exploring the “terrifying” idea of striking out on her own. The result is Natural Disaster (July 28) a dappled, jangly, and unabashedly sincere amalgam of ’70s AM-radio rock and peak-era Sheryl Crow filtered through a lens of lo-fi California cool.

These days, the cemetery — a verdant, hilly sprawl just up the road from the house she bought several years ago — is a place Cosentino goes regularly to reflect and ramble and sometimes just sit in her car, writing songs. “I used to be very afraid of death,” the 36-year-old Glendale native says, pulling into a parking spot. “But it’s become part of my practice of softening. That’s my emo reason for coming here.”

The Forest Lawn guest experience, it turns out, is more pastoral Disney dream of the afterlife — Walt, naturally, is also buried here — than Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride. Even under June-gloom skies, its vast acreage is dotted with fresh flowers and family members having makeshift picnics around the gravestones of loved ones; on one freshly tilled hillside, a stand of bright carnations spells out MR. JONEZ in jaunty block letters. As she wanders, Cosentino leads an informal tour, stopping by the on-site museum to admire an oil painting of one particularly beatific Jesus (“He’s, like, smizing”), saying hello to the property’s marauding gangs of geese (“I call them my cemetery puppies”), and moving unhurriedly through a maze of crypts, statuaries, and tucked-away small chapels.

Over the next several hours, she also roams easily and earnestly across her history: the winding journey of the now “indefinitely paused” Best Coast; her secret foray into solo-dom; her long-lens take on the indie-rock Me Too movement she helped foment. Most of all, she’s intent on showcasing the hard-won, well-therapized work of cracking “the Bethany that was behind 17 layers of glass.”

You didn’t announce the album until it was completed. Why keep it a secret?

I was 22 when Best Coast started, and I’ve always been a really forward-facing person. Very rarely do I hold back from my opinions, that’s for sure. [Laughs.] But I just felt like I was going through such an identity shift. I knew that what I was doing was going to be very different because I felt like a totally different person, and I didn’t want anybody to have access to that while I was still figuring it out. Because I have a very neurotic brain, the worst parts of me were like, People are just going to think I’m doing nothing with my life: “What does she do all day, sit on the couch?” I mean, the record’s inception was in 2020. It’s been a long hibernation. So when it came time to release it I was like, Oh my fucking God, can I just get this out of me already? [Laughs.] But I’m glad that I held it in. I think I would’ve been a lot more inclined to worry about what people were going to think if I had put it out early. That didn’t even cross my mind while I was making it — I don’t care, because guess what? No one knows that this is even real! So it was a cool experience of keeping my mouth shut for once.

Was there a moment when the idea of going out on your own crystallized?

It was 2020, after the last Best Coast record came out. We were on tour and COVID happened two weeks in. I always felt like if I was going to make a solo record and walk away from Best Coast, I needed to have a legit reason. And what better reason is there than the planet literally shuts down and everybody is sort of forced to go inward and reevaluate and ask themselves, What is it that I want out of life? I realized that I just don’t feel like that thing anymore. And if I don’t feel genuinely connected to something, I can’t fake it. I’m such a bad faker. Because of the slowness of the world, it gave me the opportunity to be like, Oh, I can actually do this. I got to just go be Bethany.

How did that conversation go with your bandmate, Bobb Bruno?

I brought Jersey Mike’s because Bobb and I love Jersey Mike’s. We had really been trying to get this tour back up and running, and it started to really feel like Always Tomorrow was light-years away. I felt so disconnected from it. I felt so disconnected from the person that I was when I made it. And so when I expressed that to him, he understood. He’s been my friend since I was 16. He’s a lot older than me, and he has always been a person in my corner. I had so much anxiety of He’s gonna be mad at me, he’s gonna think I’m abandoning him. And he was like, just consistently over and over, “I’m not mad at you.”

I don’t believe in the finality of things when it comes to creative projects. I don’t think that you have to end something definitively to go and do something else. It’s a pause. I’m going to go explore being a different person. And I can always return if I want to. I do see Best Coast at some point down the line doing an anniversary show. But as far as having that be the top priority of my artistic life, I just outgrew it. I don’t think it had anything to do with Bobb. Best Coast had always been my way of storytelling and my way of sort of walking through the world, and I felt I had reached a property line. So at the end of the day it was like, “This has nothing to do with you. This has nothing to do with the sonic sound of the band. This just has to do with me as an autonomous human being.” And he was like, “Yeah, you don’t need to keep explaining it to me. We’ve eaten the sandwiches, we’re done.” [Laughs.]

Maybe your creativity is just like a plant that needed to be repotted.

I literally 1 million percent made that analogy! Because I had a money plant in my house that was in desperate need of being repotted. I told my boyfriend, “I could think of Best Coast as my roots outgrew it and needed a bigger pot.” And he just kind of looked at me and was like [deadpan], “Totally, babe.” This is where the girl who took mushrooms for the first time connects to the universe. I’m sorry, I did mushrooms very late in life. [Laughs.]

What was the first song that you wrote for the record?

“It’s Fine.” I had seen something on the internet that really pissed me off, and I wanted to go on a tweet spree and just rip a person apart. And then I realized I actually don’t think I care. An old part of me wanted to create a problem and be dramatic and do the things I would’ve done when I was 22, 23, 24. But I walked over and I picked up the guitar in my living room instead.

At the time, I had been working with a different collaborator, Carlos de la Garza, who produced the last Best Coast record. He’s a close friend of mine. But it became very clear that the style of record that I was wanting to make, I needed to explore other options. And Butch Walker I knew from a million years ago because Best Coast almost made a record with him. He had a foot in alt country and Americana, which is where I kind of wanted to go. So I sent him “It’s Fine,” which was just a shitty demo on my iPhone. And he was like, “I took the liberty of putting a little bit of a track together. Is that okay with you?” He pushed PLAY and it was goosebumps all over my body. The version that’s on the record is the version from that day. It was lit.

Your lyrics are also different from your past material — songs like “Easy” and “It’s a Journey” engage with mental health and relationships and the growing pains of adulthood in really honest, unfiltered ways.

It’s interesting because I’ve made a career out of being so open and so vulnerable, but it’s always been sort of under the guise of this angsty I-don’t-care persona. It’s like, if I can share that I’m a really anxious person or I’m fucked up, that I’ve been in these toxic relationships, then somehow it makes me cool. If I share that I’m afraid of intimacy or I struggle with fear of death, then somehow I’m a little bitch. And I think that I had this real awakening within myself. Truly, a lot of it was connecting to my inner child. My parents were so protective and so loving and so supportive, but the flip side of that coin is I never got to fucking fall down and skin my knee and hurt myself because somebody was helicoptering over me so intensely. I was an only child, and my mom had a lot of miscarriages, so I was this child that she was told that she couldn’t have. Now that I’m 36 and thinking about having my own kid, I have a lot of compassion where I’m like, I get it.

But I realized that I don’t let people in in that way because I’m afraid that they’ll take all of me. Literally, I was the kid at Disneyland on the leash. No joke — there’s a picture of it on my fridge that I talk about in therapy. I couldn’t run free. And thinking back to what I was telling you about feeling like I had reached the property line with Best Coast, I had to release myself from the Disneyland leash. That’s a very heady, long-winded answer. But if people don’t get it, they just don’t get it. And that’s fine. I have to really, truly believe myself when I say it’s fine. It’s fine! Take your own fucking advice. [Laughs.]

Was the album always going to be named after the opening track, “Natural Disaster”?

Yeah. The song was very much inspired by the energy of 2020, when there was crazy political unrest and people were dying in massive amounts. I was going to Black Lives Matter protests here, and cop cars were on fire, and it felt like everything was collapsing and falling apart. It’s also 100 percent inspired by climate change, but fires and earthquakes are the natural disasters that I’m the most used to growing up here.

I feel like I had my own internal earthquake — like one piece of my core was up here [gestures to her solar plexus] and the rest of my core was down here [gestures to her knees]. And it was learning to let those two things exist. It was sort of a commentary on what do we do when the world around us is burning — we panic, and then we take that panic and we make something out of it.

For the recording process, you also ended up physically leaving the place you’re so identified with.

Yeah that’s the other thing is I made most of this record in Nashville. I’ve always been an L.A. girl, I would drive five minutes to go record in Eagle Rock. But I got on an airplane — literally got behind the wheel of a truck and was driving down dirt roads, waving hello to cows every morning going into the studio. It was a complete and utter rewrite of everything I’ve ever known.

You made a “Natural Disaster Inspo” playlist that has many of the patron saints of your new sound: Sheryl Crow, Indigo Girls, Counting Crows, Linda Ronstadt. Bonnie Raitt even gets a little namecheck on the song “Outta Time.” Was that direction always in you, waiting to get out?

I think some of that stuff was there at a surface level, or maybe an aesthetic level. When we made the second Best Coast record at Capitol Studios with Jon Brion, it was very different than the first record, which was made in like two weeks in a practice space in Echo Park. So Bobb and I were like, We wanna make our version of a Fleetwood Mac or an Eagles album or whatever. It didn’t land there, but those were definitely references that we would make in the studio a lot.

But I never would have referenced Bonnie Raitt in a Best Coast record, or any of the ‘90s country that I grew up listening to because my parents are from the Midwest. I knew all about Travis Tritt and George Strait and all these artists because of my grandmother. But I would never have walked into the studio in a Best Coast session and been like, “Let’s play ‘I’m Alright’ by Jo Dee Messina and find a way to weave it in!” The thing about Sheryl Crow is that she’s a master songwriter. You hear “Soak up the Sun” in every grocery store across the planet, and you walk out and it’s in your head all day long. And that’s because it’s a fucking fantastic melody and a great song.

Some of these songs are pretty stripped-bare ballads, like “I’ve Got News for You,” which reminded me a little bit of Crow’s “Strong Enough.”

That song was really scary because it is just piano and just my voice. And that one, we actually used the demo from the day that I wrote it. The next single is “Easy,” which is just a tried-and-true love song. I’ve never done anything like that before. So the real journey in the making of this record has been to allow myself to be corny at times. Those words would never have come out of my mouth before because I would’ve been too embarrassed. Now I’m just like, what do I have to lose? I’m in my mid-30s, I wear fucking Birkenstocks. Why not just let myself be who I feel authentically that I am?

You’ve always sung about your romantic life, but you do seem much more the main character now of your own songs.

Yeah, I don’t think I really realized how co-dependent I was. I would sort of proclaim that I was the main character to the world, but behind the scenes I was actually always trying to fix everybody else and never fix myself. I had to walk away from Best Coast [in part] because singing those songs was very painful for me — for the first time really hearing, No. 1, the pain that I was in, unbeknownst to me at the time. But No. 2, I’m tired of singing about these fucking guys; I’m tired of singing about this story. And then the realization that you’re the one that keeps doing it! Go talk about something else.

The relationship that I’m in now is the literal only healthy relationship I’ve ever been in in my entire life. And it’s terrifying. I always thought that the chaotic relationships were so hard, and I look back I’m like, Oh, that’s a walk in the park. When you’re screaming and yelling at somebody, it’s very unhealthy, but it’s also not real. I just didn’t have the capacity to walk away from those things because I was, you know, 25. And when you’re 25 and you’re not working on yourself, you’re just like, Oh, this is how it’s supposed to be. The pandemic was just the first time that I really ever got to zoom out and be like, what’s going on here? There’s a lot of shit that I thought I fixed, but I did not. I only scratched the surface, you know? That’s the thing that I’m starting to realize that annoys the shit out of me, is that it’s not a one and done. You have to consistently be working on these things until you end up at fucking Forest Lawn. [Laughs.]

A few years ago, you told the New York Times that you used to read every comment and every review. Have you been able to move past that?

I just know now that if I’m going to go hunting in the comments, my feelings are gonna get hurt. For example, when I announced this record and “It’s Fine” first came out, I was in Philly doing a promo thing and I was alone in my hotel room and I opened YouTube and I saw a comment that was like, “No thanks, this bubblegum pop isn’t for me. The cool thing about Best Coast was that they were different, this is Sheryl Crow shit.” I was like, “Well this is actually a compliment to me, so thank you!” Obviously, there is a side of me that wants to be liked and wants to do well because I’m human. A couple things that I saw on Twitter were like, “How could you do this to Bobb?” And I was like, Okay, you don’t even know the story. But I also just know that it’s self-harm if I go in the comment section, And then I have to remind myself that Kevin from New Jersey doesn’t matter. What matters is your real life. I’m mean enough to myself.

In the past few years we’ve seen a lot of reevaluations of how we treated certain female pop stars in the press and the public sphere — Britney, Janet, Alanis, Sinéad. When you look back at the aughts indie-rock scene and some of the ways that you were written or spoken about, does it seem crazy to you now?

I just think that the internet was different then, sort of close to an indie-rock TMZ. Like Hipster Runoff was a joke, right? But it was wildly hurtful. That shit fucked me up. Obviously I was in a relationship with somebody else who was a musician and we were an It couple or whatever you want to call it, but people talked about us in as close to a tabloid-y way as you could with indie rock. I was also very much reduced to several tropes — lazy, crazy, weed, cat. And I played the part because I was like, “I guess if this is what you say I am, then this is what I am.” I don’t know. I do think though that the blogosphere, which is the word that I think of when I think of that era, you just couldn’t get away with that shit now.

When you wrote that op-ed for Billboard, talking openly about bad men in the entertainment industry was still a very nascent thing. But you pretty starkly laid out the ugly experiences you’d had as a female in that world.

When I was younger I would just be like, “I have a platform, I have a phone, I’m gonna type this thing and send it.” But when I woke up the next morning, it was the classic thing of, like, Fuck. I was gaslighting myself: Oh no, I just ruined a person’s life, blah blah blah. Because that was pre–cancel culture, pre–Me Too. And I remember very shortly after that, I got asked to go on The Daily Show and sit with Trevor Noah and talk about sexism in the music industry. It was really scary for me because I was like, am I qualified to speak on this topic? Is this something that I even understand enough? Am I the right spokesperson for this? But I think at the end of the day, I’m really grateful for that moment. Because after that I feel like people started speaking out more about bad promoters, guys in bands. If I inspired anybody to speak up about something that was happening to them, I would gladly hold those uncomfortable feelings knowing that I helped somebody else. But yeah, I don’t think I really realized at the time the impact that it would have. It was truly just a “send tweet” moment and then down the tower went.

You seem to enjoy social media now on your own terms. Does it feel like you have more agency and more of your actual self in it than you might have had on, say, MySpace once upon a time?

There are two versions of an artist, right? There’s the very elusive one that’s not online and they don’t really give you anything. And then there’s the person that’s sort of like, “Hey guys, here I am at Trader Joe’s. Hey guys, here I am at the gym. Hey guys!” Sometimes I have moments where I’m like, “Well, if I don’t share all the things then I’m not relatable anymore.” But there’s also certain things that I’m not gonna do. I’m a 36-year-old woman, I don’t need to be dancing on TikTok, you know? But there are some people in the industry that would tell you no, you need to do the dance. I’m not gonna do the dance. Literally and figuratively. [Laughs.]

But you will go Zapruder-deep on Vanderpump Rules.

I actually tweeted the other day, “I’m done with the hot takes from people who are brand new to the Vanderpump Rules universe because of Scandoval. I don’t want to hear your opinion unless you’ve been with us since day one in the trenches.” I’ve been watching these people for ten seasons! I’ve gone through a lot with them. It’s funny because on the last Best Coast record, I had four of the people from Vanderpump Rules in a music video and two of them are Tom and Ariana, the center of the Scandoval. And I remember there were people that were like “This is dumb, why do you like this show?” But I don’t believe in guilty pleasures. What I like is what I like. My straight 43-year-old fiancé likes Vanderpump Rules now, and so does a 16-year-old in Missouri. The thing that unites us as a society is our love of these crazy people. I know Ariana personally, and she’s an angel, and I was not happy when I found out. No one was, obviously — look what fucking happened.

Do you get recognized much out in the wild?

Every so often I do. Somebody just ran up to me at the mall the other day. I was at a Foot Locker looking at shoes, and this kid was like, “So sorry to bother you, I just wanted to say your music changed my life. Have a good day — I hope you find a cool pair of shoes!” And then the rest of my day was so nice. The other thing that I get a lot is “You were my favorite artist in high school.” And I’m like, “I’m still an artist, I’m still here, but thank you!” Like, Rilo Kiley was my favorite band in high school, and I know Jenny now, she’s the nicest person, and even when I’m around her still I’m like [awed whisper], “This is Jenny Lewis.” She’s the coolest. But those records were so formative for me, and I realized that Crazy for You in particular was a seminal record for a lot people in that era of their teen years or 20s. So sometimes when kids say stuff like, “You were my favorite,” and I feel my ego be like, “You’re a loser, no one likes you anymore,” I have to separate that, because I don’t think Jenny Lewis is a loser for making my favorite records from high school; I think she’s a queen and an icon. It’s okay — it’s a compliment! Just accept it.

I know there are some Best Coast tattoos out there too.

There are people that have tattoos of Snacks, which is crazy. Those ones specifically touch my heart. It really felt like when he died — he was almost like the mascot, because he came into my life as Best Coast was starting and he exited as we were going on this break. He was such an emotional-support presence through all of those records. Now I’m having to be my own emotional-support cat. This necklace that I’m wearing actually has his ashes in it. I’m friends with Vanessa Carlton, and she had a similar relationship with her dog. She was like, “I have him in this necklace, you should do the same.” So I did and it’s so nice, it’s like he’s with me all the time. It looks like a Tic Tac, but it’s actually Snacks.

Are you going to be touring for Disaster? Would you want to headline or support someone?

It’s weird because I’m not new but I’m new, right? I can’t automatically play the places Best Coast was playing. So I kind of feel like the new kid on the block in certain ways. But yeah, the plan is to do some of my own shows in the fall and then potentially support somebody if the right opportunity comes along.

Are you hoping that one of the people on your inspo playlist might need an opener?

Yeah, for sure. We have big goals over here. [Laughs.] At the end of the day, obviously I want this to succeed, but I feel like I’ve already succeeded because I did the thing that I wanted to do. It did come with a lot of shedding of narratives and it was very, very, very internally painful. But the actual process was rather easy — it all lined up and everything sort of led me to the spot that I’m at now. So if at the end of the day, you know, the Chicks don’t come knocking, Sheryl Crow doesn’t come knocking, that’s okay. But there’s a side of me that really feels like good things will happen because when something is right, it’s just right.

This interview is edited and condensed.