It’s big, perhaps the size of a country or even a continent. It’s garbage, composed of all the detritus humans discard without a second thought. And it’s a myth. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is not, as popularly portrayed, a solid mass of floating waste somewhere in the middle of the ocean. If it were, developers might well be selling beachfront homes, promoting it as an exciting opportunity to live on a brand-new, man-made island. Rather, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is more like a swirling vortex of garbage, some of it floating and some of it submerged, that may be thick enough to create dead zones or thin enough to be little more than a nuisance. After all, people have dumped more garbage in oceans than in landfills, and it all has to go somewhere. While the Great Pacific Garbage Patch might not be the next new continent, that popular image has been used to create interventions that have brought about real change.

A piece of art made out of trash by Bonnie Monteleone (2011) to illustrate the Great Pacific Garbage Patch first described by Charles Moore.

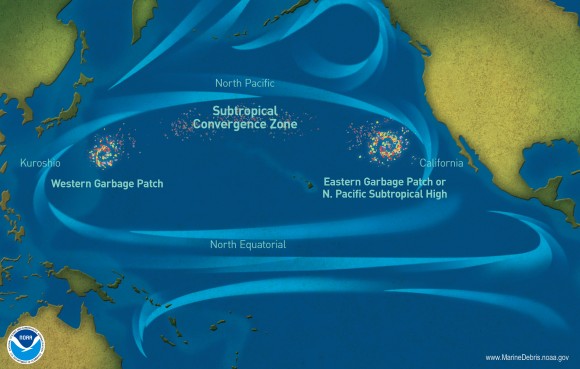

The story of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch began when Charles Moore was sailing across the ocean and encountered strange objects bobbing in the water. His discovery was less “Land ahoy!” than “There’s a lot of garbage here,” and Moore started to wonder whether his individual journey was indicative of a greater problem (2009a). After his initial encounter in 1997, he started investigating trash in the oceans further, particularly garbage that gets caught up in gyres, or rotating vortices of ocean currents created by wind and the Coriolis effect (Moore, 2009a; Turgeon, 2014). When Moore came forward with his findings, the media dubbed the garbage caught up in the gyre in the Eastern Pacific the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” and the idea caught on a life of its own. A Russian source called it “trash island” (Engber, 2016). Like pollution in general, everyone began using the term, although the reality is a lot more noxious and has a much greater potential to affect everyone than we like to acknowledge.

Garbage from beaches, tributaries, and waste dumped at sea gets trapped in ocean currents and tends to congregate in distinct regions; the detritus in the Eastern Pacific is colloquially referred to as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2012).

As fantastical as an island of garbage might seem, the reality is even more disturbing. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is made mostly of tiny bits of trash too small to see from a satellite or even notice while sailing through it, although there are the odd large items like a truck tire or a volleyball to serve as a more intact reminder of mankind (Engber, 2016). These pieces of garbage are normally so small because objects caught in a gyre get churned up along with the ocean’s currents, breaking them down into a sort garbage slurry that creatures like shrimp and fish confuse for food (Turgeon, 2014). “Plastic comes in every size-class and mimics the food for every single trophic level,” Moore tells Earth Island Journal in a 2009 interview. “From the tiniest zooplankton all the way to the largest cetaceans, there is a plastic morsel that looks and acts just like their natural food.” To prove his point, he sampled a series of fish at the bottom of the food chain. He found over a third of the fish had eaten plastic particles, and he found 84 pieces of plastic in the stomach of a 2 1/2-inch fish (Moore, 2009b). The little fish’s confusion may be understandable given how much plastic is now in the oceans. Moore (2009b) found 46 pieces of plastic per plankton in samples of ocean water, about an eightfold increase from the previous decade. Beyond the effects on fish, and on every creature higher on the food chain that might eat said fish, marine pollution is transported around the globe via the ocean’s currents. Just like the trash came into the gyre from somewhere, it may leave the gyre to somewhere else. Beaches across the North Pacific now have plastic sand deposited on their shores from the sea slurry instead of from rocks and shells (Moore, 2009a). While the idea of a confetti-colored beach might seem appealing–imagine the sandcastles!–it hides a far uglier truth: We are irreparably damaging the environment, and the relics of our refuse will remain far longer than we will.

Anna Cummins (2008), a crewmember of Moore’s, shares pictures of plastic pieces mixed with sand, at the top, and plastic soup from the Pacific, at the bottom.

It might be easier for the media to report and for people to discuss an island of garbage than the uncomfortable truth of environmental damage, particularly since it may pertain to human health as well. From studies involving birds that ate plastic particles, Moore (2009a) concludes that plastic can deliver other pollutants into living tissues, affecting the circulatory, endocrine, and reproductive systems. There is now such a high concentration of plastic particles in the ocean that Moore tells interviewer Thomas Kostigen (2008), “You can now make a new hypothesis that all food in the ocean contains plastic.” Of course, that would be within the food, not just wrapped around it. It seems like the food chain might come right back around to bite the producer of the plastic in the end.

Whether inspired by the media-mongered myth or the frightening facts, the idea of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch has prompted people to take action. Every ocean and major body of water has a garbage patch of its own (Jeftic, Sheavly, & Adler, 2009). With such a global issue, a global solution must emerge. The United Nations has taken the initiative and passed resolutions to study, address, and reduce marine litter, as well as sponsoring regional cleanup efforts to stop pollution at the source and clean up beaches (Jeftic, Sheavly, & Adler, 2009). As an implementation of collaborative feedback, which is used to provide information on how one’s peers are faring on a certain measure, and injunctive norms, which are informal rules set by the community for what constitutes proper behavior and can be informed by collaborative feedback, the United Nations also publishes a comparative contribution of countries to cleanup efforts, and it is also trying to source trash sampled from the oceans back to its origin and share that information as well (Jeftic, Sheavly, & Adler, 2009). Other organizations have subtly implemented social psychology in their interventions as well. LUSH and 5 Gyres Institute held the “Ban the Bead” campaign at the cosmetics company’s stores. The campaign aimed to educate consumers about the dangers of plastic microbeads used in soaps and cosmetics, but LUSH also asked its customers to sign a petition to limit the use of microbeads and just happened to sell a new, limited edition scrub, “Life’s a Beach,” in conjunction with the awareness campaign (LUSH, 2016). While the company did donate the proceeds from this scrub to 5 Gyres and other environmental charities, it is quite possible the product would never have sold if consumers were not made aware of the issue and commit to take action, creating a situation of cognitive dissonance similar to that produced by Dickerson, Thibodeau, Aronson, and Miller in their classic 1992 water conservation experiment. The state of cognitive dissonance describes the discomfort a person experiences when their thoughts are not in line with their actions, and to reduce that discomfort a person must either change their thoughts or their actions. In this case, LUSH simultaneously threatened its customers’ self-image as environmentally-conscientious people, as asking customers to sign a petition to reduce behavior they likely engaged in created a state of dissonance, and provided a solution to that conflict: Buy our product. It could not have worked out more perfectly for LUSH if an applied social psychologist had designed it; perhaps one did.

LUSH’s “Ban the Bead” campaign, with its semi-eponymous hashtag, coincided with a new release of a natural exfoliant product (image from Heather, 2015).

Whether the interventions are local and intended to boost a company’s image and bottom line or international and aimed at stopping plastic pollution at the national level, applied social psychology and environmental psychology have been implemented to address marine pollution due to the myth of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Much like it took a world of people to produce the garbage in that patch, it might take a world of people to eliminate it as well. More than this, the oceans and the debris found in them have, in a strange sense, united humanity. Thomas Kostigen (2008) found remains from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch on a Hawaiian beach that represented an array of human cultures: “I found pill bottles from India and mashed pieces of various products–oil containers, detergent jugs, plastic caps–with Russian, Korean, and Chinese writing on them.” Our trash can affect others halfway around the world, an unintended relic of culture and evidence for the interconnectedness of life on Earth. It is quite remarkable that one such creature has extracted the remains of giant lizards, remains that had been compressed for millions of years, and formed them into bottles, nose hair trimmers, and even toys modeled after those same giant lizards and sent them to be played with and used by others around the world. Is it any more remarkable to consider that these same creatures might find a way to rescue that plastic from the oceans or prevent it from getting there in the first place?

References

Cummins, A. (2008, September 1). Sea of garbage. New Internationalist Magazine. Retrieved from https://newint.org/features/2008/09/01/sea-of-garbage/

Dickerson, C.A., Thibodeau, R., Aronson, E., & Miller, D. (1992). Using cognitive dissonance to encourage water conservation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22, 841-854. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1992.tb00928.x

Engber, D. (2016, September 12). There is no island of trash in the Pacific. Slate. Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/the_next_20/2016/09/the_great_pacific_garbage_patch_was_the_myth_we_needed_to_save_our_oceans.html

Heather, N. (2015, July 3). #banthebead with LUSH [Image]. Ivory Avenue. Retrieved from http://ivoryavenue.com/2015/07/banthebead-with-lush/

Hennen, D. (2012, January 18). Marine debris: One huge problem [Image]. Retrieved from http://normalbiology.blogspot.com/2012_01_01_archive.html

Jeftic, L., Sheavly, S., & Adler, E. (2009, April). Marine litter: A global challenge. United Nations Environment Programme. Retrieved from http://www.unep.org/regionalseas/marinelitter/publications/docs/Marine_Litter_A_Global_Challenge.pdf

Kostigen, T.M. (2008, July 10). The world’s largest dump: The Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Discover. Retrieved from http://discovermagazine.com/2008/jul/10-the-worlds-largest-dump

LUSH. (2016). Ban the bead. Retrieved from http://www.lushusa.com/on/demandware.store/Sites-Lush-Site/en_US/Stories-Article?cid=article_ethical-ban-the-bead

Monteleone, B. (2011). Plastic ocean [Image]. Retrieved from http://environmentalhumanities.dukejournals.org/content/7/1/203/F8.expansion.html

Moore, C. (2009). Captain Charles Moore talks trash. Earth Island Journal. Retrieved from http://www.earthisland.org/journal/index.php/eij/article/charles_moore/

Moore, C. (2009, February). Charles Moore: Seas of plastic [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.ted.com/talks/capt_charles_moore_on_the_seas_of_plastic?language=en#t-7570

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2012). Great Pacific Garbage Patch [Image]. Retrieved from https://marinedebris.noaa.gov/movement/great-pacific-garbage-patch

Turgeon, A. (2014, October 4). Ocean gyre. In National Geographic’s online encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/ocean-gyre/

Excellent informative post I like that you used pictures too, it gave me a clear picture of everything that you were referring to in your post. I think it’s fair to say that humanity is still trying to find a way to live in our planet without harming it. It’s only in the 20th and 21st century that we are able to show people across all states, by broadcasting, the effects that things as the pacific garbage patch has on our eco system. I do agree that it will take really strong efforts to get rid of the garbage patch, as it will take really strong efforts to eliminate many of the other things that are slowly but surely killing and polluting the natural resources in our planet. I’m happy to see that there are companies out there such as Lush that are willing to have campaigns such as “Ban the Bead” I believe I read somewhere a couple months ago that environmentalist have been able to prove the harmful effects of beads in scrubbing products and soon microbeads will be eliminated across all brands. This is only a baby step in our journey to saving the ocean, however, I do hope that there are many more steps to come.