Rwanda

Remembering the Rwandan Genocide: Kigali Memorial Centre

1994 marks a dark year for Rwanda. The year of Genocide.

The Rwandan genocide resulted in the systematic massacre of 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus (the two main Rwandan ethnic groups) in less than 100 days. All while the international community closed its eyes.

Lasting 100 days this devastating massacre tore apart neighbours, families, friends and communities.

The Kigali Memorial Centre pays tribute to Rwanda’s recent tragedy. It is an intensely powerful and moving memorial for which you should dedicate at least half a day.

The Kigali Memorial Centre pays tribute to Rwanda’s recent tragedy. It is an intensely powerful and moving memorial for which you should dedicate at least half a day.

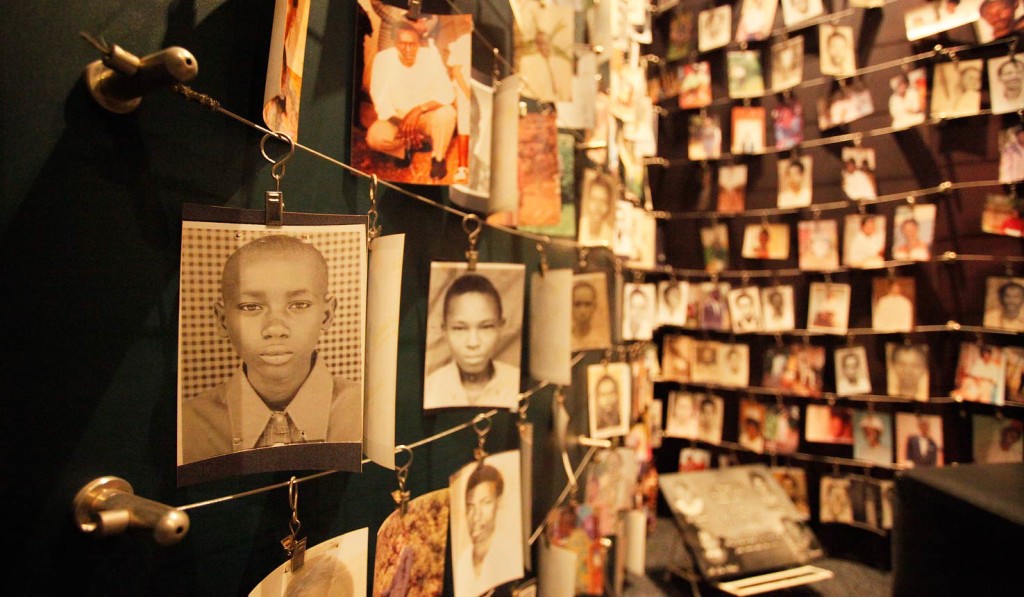

The informative audio tour (US$15) includes background on the divisive colonial experience in Rwanda and as the visit progresses, the exhibits become steadily more powerful, as you are confronted with the crimes that took place here and moving video testimony from survivors. If you have remained dispassionate until this point, you’ll find that it will all catch up with you at the section that remembers the children who fell victim to the killers’ machetes. Life-sized photos are accompanied by intimate details about their favourite toys, their last words and the manner in which they were killed.

The memorial concludes with sections on the search for justice through the international tribunal in Arusha as well as the local gacaca courts (traditional tribunals headed by village elders).

Upstairs is a moving section dedicated to informing visitors about other genocides that have taken place around the world and helps set Rwanda’s nightmare in a historical context.

Upstairs is a moving section dedicated to informing visitors about other genocides that have taken place around the world and helps set Rwanda’s nightmare in a historical context.

After you’ve absorbed the museum displays you can take a rose (by donation) to leave on one of the vast concrete slabs outside that cover the mass graves. There’s also a wall of names, a rose garden and a pleasant cafe serving good coffee, lunch buffets (RFr3000), snacks and juices that is an ideal place to reflect and gather yourself before facing the outside world again.

The Kigali Memorial Centre is located in the northern Kisozi district of the capital, which is a short moto ride from the centre (RFr500 to RFr600).

I knew very little of this incredible tragic event until I spent a day in the country, but I have included a short (but very useful) history of the genocide found here.

Beginning on April 6, 1994, Hutus began slaughtering the Tutsis in the African country of Rwanda. As the brutal killings continued, the world stood idly by and just watched the slaughter. Lasting 100 days, the Rwanda genocide left approximately 800,000 Tutsis and Hutu sympathizers dead.

The Hutu and Tutsi are two peoples who share a common past. When Rwanda was first settled, the people who lived there raised cattle. Soon, the people who owned the most cattle were called “Tutsi” and everyone else was called “Hutu.” At this time, a person could easily change categories through marriage or cattle acquisition.

It wasn’t until Europeans colonisation in Rwanda that the terms “Tutsi” and “Hutu” took on a racial role. The Germans were the first to colonize Rwanda in 1894. They believed the Rwandan people and thought the Tutsi had more European characteristics, such as lighter skin and a taller build. Thus they put Tutsis in roles of responsibility and power in the country.

When the Germans lost their colonies following World War I, the Belgians took control over Rwanda. In 1933, the Belgians solidified the categories of “Tutsi” and “Hutu” by mandating that every person was to have an identity card that labeled them either Tutsi, Hutu, or Twa. (Twa are a very small group of hunter-gatherers who also live in Rwanda.)

Although the Tutsi constituted only about ten percent of Rwanda’s population and the Hutu nearly 90 percent, the Belgians gave the Tutsi all the leadership positions. Naturally, this upset the Hutu.

When Rwanda struggled for independence from Belgium, the Belgians switched the status of the two groups. Facing a revolution instigated by the Hutu, the Belgians let the Hutus, who constituted the majority of Rwanda’s population, be in charge of the new government. This upset the Tutsi.

The animosity between the two groups continued for decades. But it was’t until 8:30 p.m. on April 6, 1994, that things really heated up.

It was the night that President Juvénal Habyarimana of Rwanda was returning from a summit in Tanzania when a surface-to-air missile shot his plane out of the sky over Rwanda’s capital city of Kigali. All on board were killed in the crash.

Since 1973, President Habyarimana, a Hutu, had run a totalitarian regime in Rwanda, which had excluded all Tutsis from participating. That changed on August 3, 1993 when Habyarimana signed the Arusha Accords, which weakened the Hutu hold on Rwanda and allowed Tutsis to participate in the government. This greatly upset Hutu extremists.

Although it has never been determined who was truly responsible for the assassination, Hutu extremists profited the most from Habyarimana’s death. Within 24 hours after the crash, Hutu extremists had taken over the government, blamed the Tutsis for the assassination, and begun the slaughter.

The killings began in Rwanda’s capital city of Kigali. The Interahamwe (“those who strike as one”), an anti-Tutsi youth organization established by Hutu extremists, set up road blocks. They checked identification cards and killed all who were Tutsi. Most of the killing was done with machetes, clubs, or knives. Over the next few days and weeks, road blocks were set up around Rwanda.

On April 7, Hutu extremists began purging the government of their political opponents, which meant both Tutsis and Hutu moderates were killed. This included the prime minister. When ten Belgian U.N. peacekeepers tried to protect the prime minister, they too were killed. This caused Belgium to start withdrawing its troops from Rwanda.

Over the next several days and weeks, the violence spread. Since the government had the names and addresses of nearly all Tutsis living in Rwanda (remember, each Rwandan had an identity card that labeled them Tutsi, Hutu, or Twa) the killers could go door to door, slaughtering the Tutsis.

Men, women, and children were murdered. Since bullets were expensive, most Tutsis were killed by hand weapons, often machetes or clubs. Many were often tortured before being killed. Some of the victims were given the option of paying for a bullet so that they’d have a quicker death.

Also during the violence, thousands of Tutsi women were raped. Some were raped and then killed, others were kept as sex slaves for weeks. Some Tutsi women and girls were also tortured before being killed, such as having their breasts cut off or had sharp objects shoved up their vagina.

Thousands of Tutsis tried to escape the slaughter by hiding in churches, hospitals, schools, and government offices. These places, which historically have been places of refuge, were turned into places of mass murder during the Rwanda Genocide.

One of the worst massacres of the Rwanda genocide took place on April 15-16, 1994 at the Nyarubuye Roman Catholic Church, located about 60 miles east of Kigali. Here, the mayor of the town, a Hutu, encouraged Tutsis to seek sanctuary inside the church by assuring them they would be safe there. Then the mayor betrayed them to the Hutu extremists.

The killing began with grenades and guns, but soon changed to machetes and clubs. Killing by hand was tiresome, so the killers took shifts. It took two days to kill the thousands of Tutsi who were inside.

Similar massacres took place around Rwanda, with many of the worst ones occurring between April 11 and the beginning of May.

To further degrade the Tutsi, Hutu extremists would not allow the Tutsi dead to be buried. Their bodies were left where they were slaughtered, exposed to the elements, eaten by rats and dogs.

Many Tutsi bodies were thrown into rivers, lakes, and streams in order to send the Tutsis “back to Ethiopia” – a reference to the myth that the Tutsi were foreigners and originally came from Ethiopia.

For years, the Kangura newspaper, controlled by Hutu extremists, had been spouting hate. As early as December 1990, the paper published “The Ten Commandments for the Hutu.” The commandments declared that any Hutu who married a Tutsi was a traitor. Also, any Hutu who did business with a Tutsi was a traitor. The commandments also insisted that all strategic positions and the entire military must be Hutu. In order to isolate the Tutsis even further, the commandments also told the Hutu to stand by other Hutu and to stop pitying the Tutsi.*

When RTLM (Radio Télévison des Milles Collines) began broadcasting on July 8, 1993, it also spread hate. However, this time it was packaged to appeal to the masses by offering popular music and broadcasts conducted in a very informal, conversational tones.

Once the killings started, RTLM went beyond just espousing hate; they took an active role in the slaughter. The RTLM called for the Tutsi to “cut down the tall trees,” a code phrase which meant for the Hutu to start killing the Tutsi. During broadcasts, RTLM often used the term inyenzi (“cockroach”) when referring to Tutsis and then told Hutu to “crush the cockroaches.”

Many RTLM broadcasts announced names of specific individuals who should be killed; RTLM even included information about where to find them, such as home and work addresses or known hangouts. Once these individuals had been killed, RTLM then announced their murders over the radio.

The RTLM was used to incite the average Hutu to kill. However, if a Hutu refused to participate in the slaughter, then members of the Interahamwe would give them a choice — either kill or be killed.

Following World War II and the Holocaust, the United Nations adopted a resolution on December 9, 1948, which stated that “The Contracting Parties confirm that genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they undertake to prevent and to punish.”

Clearly, the massacres in Rwanda constituted genocide, so why didn’t the world step in to stop it?

There has been a lot of research on this exact question. Some people have said that since Hutu moderates were killed in the early stages then some countries believed the conflict to be more of a civil war rather than a genocide. Other research has shown that the world powers realized it was a genocide but that they didn’t want to pay for the needed supplies and personnel to stop it.

No matter what the reason, the world should have stepped in. They should have stopped the slaughter.

The Rwanda Genocide ended only when the RPF took over the country. The RPF (Rwandan Patriotic Front) were a trained military group consisting of Tutsis who had been exiled in earlier years, many of whom lived in Uganda.

The RPF were able to enter Rwanda and slowly take over the country. In mid July 1994, when the RPF had full control, did the genocide stop.