Scientists have discovered a three-dimensional shape, dubbed a scutoid, that is entirely new to geometry, according to a study published in the journal Nature Communications.

An international team of researchers demonstrated that epithelial cells—the "construction blocks" of organisms that cover the surfaces of many organs, such as the skin—take the form of the previously undescribed shape, which enables them to pack tightly together and form complex, curved structures.

"[The cells] are like pieces of Tente or Lego from which animals are made," Luisma Escudero, a biologist from the Spain's University of Seville and author of the study, said in a statement.

"The epithelia form structures with multiple functions, like forming a barrier against infections or absorbing nutrients," he said. "In this way, during the development of an embryo, it changes from a simple structure formed from only a handful of cells to an animal with very complex organs."

During the growth of the organisms, the epithelial cells start joining and locking together. Previously, scientists represented these cells as being prism-shaped or like truncated pyramids. However, no direct evidence for this has been found due to the difficulty of imaging the tiny structures.

"Studies about epithelial cells have focused mostly on one side [surface] of these cells, in part due to technical limitations, and extrapolated that surface as a proxy for their three-dimensional structure," Javier Buceta, a professor in the Bioengineering Department at Lehigh University, told Newsweek.

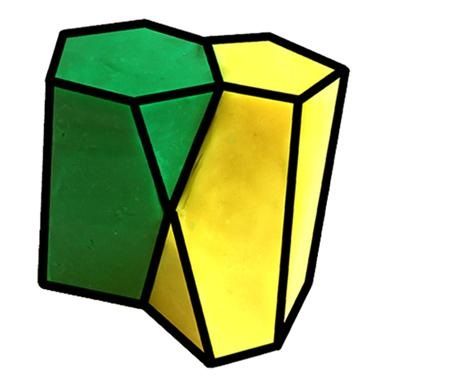

So to shine a light on how exactly these cells lock together, the researchers created computer simulations of curved tissues. They found that the only way to re-create certain patterns seen in real epithelial cells was for them to adopt the scutoid shape—which could be described as a "twisted prism," the researchers said.

Knowing what to look for, the scientists then went hunting for scutoids in real tissue, finding them in the epithelial cells of fruit flies, zebra fish and mammalian tissue. The findings suggest that the scutoid is nature's preferred solution for creating stable, curved tissue.

"The shape came as a surprise!" Buceta said. "We then discovered that this shape didn't even have a name in math."

The study could have implications for a variety of fields, ranging from mathematics to biomedicine. Specifically, it could help scientists better understand how organs are formed during their development and, consequently, how certain diseases develop when this process is disrupted.

Scientists say their next step is to identify the specific molecules that cause the cells to adopt the scutoid shape.

"In the medium term, we will be able to begin to try to apply this knowledge to the creation of artificial tissue and organs in the laboratory, a great challenge for biology and biomedicine," Escudero said.

This article has been updated to include additional comments from Javier Buceta.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.