Peter Weir: In a Class by Himself : Disney gambles that summer audiences will tire of sequels and look for more challenging fare

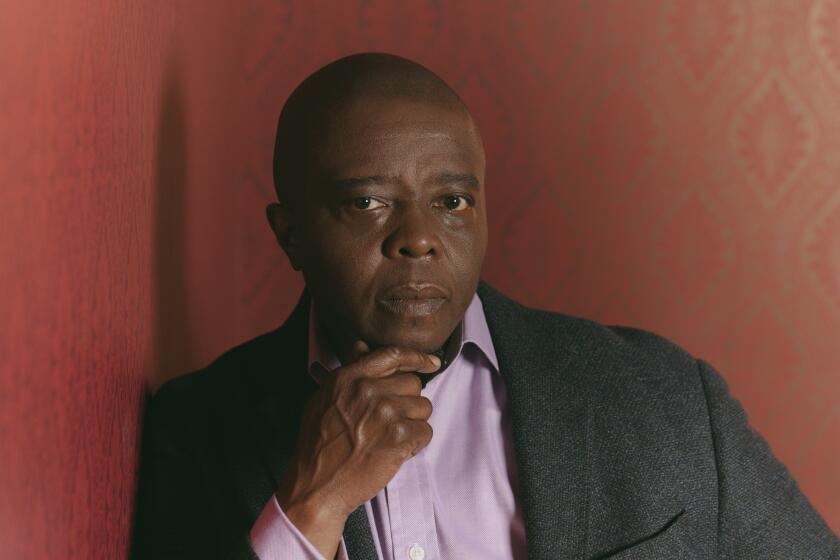

Peter Weir was one of the prime figures in the extraordinary explosion of talent that for a heady time in the 1970s made Australia the world’s dynamic new center of film creativity.

Weir is now party to a daring experiment to see whether the summer audience is ready for something more (a great deal more) than what is regarded as traditional summer fare.

“Dead Poets Society,” which opened on Friday, was directed by Weir from an original script by Tom Schulman. Robin Williams--in a finely controlled and beautifully affecting performance--is a charismatic new English teacher at a stuffy and very conservative New England prep school in 1959.

He fires up his students to a fervor of independent thought that not all of them can handle. There are thematic echoes of Muriel Spark’s “The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie,” although the emphasis in “Dead Poets Society” is more on the seven principal boys in his class than on the teacher himself.

It is a terrific film, but will it sell to a target audience that itself has in the main just departed the classroom in a mixture of exhaustion, loathing and relief?

The traditional end-of-school, thank-God-it’s-summer film is sexy, usually violent or at least action-filled, lightweight, porous, frequently set in peachy, beachy weather, youthful in spirit and usually in cast as well, upbeat and untroubling. “Indiana Jones and The Last Crusade” and “Batman” are supreme summer fare.

The primary setting of “Dead Poets Society” is the classroom, the time is fall and winter, chill and gloomy, the humor (wonderful while it lasts) yields to tension and tragedy. While the resolution is satisfying, it is also somber, and the resonances linger on into the foyer and onto the street.

Among those feeling some anxiety about Disney-Touchstone’s bold gamble is, not unnaturally, Weir himself.

“The decision grows out of Jeff Katzenberg’s instincts,” Weir said during a brief stop in Los Angeles a few days ago. (Katzenberg is Touchstone’s intense chief of production.) “His sense was that the audience was turning, getting bored with the usual summer stuff. Jeff said the summer openings have the highest number of sequels there’ve ever been. He said, ‘It feels tired. I think we should go out with something else.’

“Not many agreed with him. I wasn’t sure I did myself. The worry was that ‘Dead Poets Society’ was too fragile. But Jeff said, ‘I’ve never seen a summer film; I’ve only seen good films or bad films.’ He believes firmly that you shouldn’t stand still; you should always be trying new approaches. So this is a new approach,” Weir added with a wry grin.

The filmed opened in some 600 theaters across the country, with plans to go wider quickly if, as Katzenberg & Co. expect, there are favoring reviews to quote from in the ads.

Schulman’s script drew on his own experiences in private school, and Weir himself had no trouble identifying with the material. “I was in prep school myself in exactly that year, 1959.” The school was The Scots College in Sydney, very strict and very conservative. “If there’d been a Dead Poets Society”--in the film, a secret society for the school’s free-thinking mavericks--”I’d have been in it.” Disciplining via a hard whacking with paddle or cane was the rule at Scots as well as the fictional Welton Academy and, “I got my share of the cane,” Weir says.

As a child in Sydney, Weir had worshipped the Saturday matinees with their thrillers and serials but lost interest in the movies in his teens. The Vietnam War, which brought conscription to Australia as well as the U.S., and with it the same angry protests among the young, rekindled in Weir an interest in films.

Weir feels that in fact Vietnam was one of the causative factors in the sudden burst of creativity in Australian film making.

“The 16mm camera became the symbol of revolution and anger, like the AK-47 is now, I suppose. If you could only film whatever it was you wanted to say, you could do something about it. We had no tradition of features, important features, in Australia. But when I was in my 20s we were getting into the film-festival generation, seeing what was being done in other places.”

Weir’s first low-budget feature, “The Cars That Ate Paris,” made in 1971 when he was still in his mid-20s, has become a cult classic in the comedy-horror genre. “Picnic at Hanging Rock” three years later has classic status as well, for its eerie telling of some mysterious and never-explained disappearances of a schoolmistress and three of her students during a class outing. (“That was my previous attempt at a school film,” Weir says.)

“The Last Wave” and “Gallipoli” brought Weir into the embrace of Hollywood, for whom he has done “The Year of Living Dangerously,” the hugely successful “Witness,” the not so successful “The Mosquito Coast” and now the quiet and thought-provoking “Dead Poets Society.”

The film’s casting agents looked at nearly 1,000 boys, in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and Canada, before Weir at last chose the seven principal players. “I insisted that no one could be over 20, none of these high schoolers who look like graduate students. The final criterion was that I had to like them. We all had to get along.” (There are reports that one 30-year-old ringer got past Weir, but the boys look like boys.)

While Williams was finishing the run of “Waiting for Godot” with Steve Martin in New York, Weir brought the boys to St. Andrews School in Delaware (whose trustees had approved letting the school pose as Welton) for a week of what he called not rehearsal but workshops.

“I banned all contemporary phrases,” says Weir. “They had to speak in simple sentences, but complete sentences. ‘Right on ‘ was out and so were ‘like’ and ‘you know’ and ‘Aw right .’ It’s remarkable how much intonations have changed over the years, if you listen and think about it.

“We did exercises, improvisations, to loosen everybody up, and we had a lot of laughs.” Weir also gave the actors 15 minutes to write an original poem (paralleling an exercise in the script). “Some of the work was very good indeed.”

He didn’t let the boys watch the dailies when shooting started. “I wanted to remove any competitiveness and simply let the energy come out. Kids appear to be much cooler than our generation was, but I’m not at all sure of it.” Weir has two teen-agers, a daughter and a son; the son is briefly seen in a straw boater in a picture-taking scene at the start of the film.

“The only real problem in making a film is the script,” says Weir, “and the worst problem of all is having to start without knowing how to end it. I only had it like that once, and never again; every day was an agony.

“The physical aspects come with the job. These days you can command top people who handle the logistics. Then you can deal with the intrinsic subject matter. If it’s right, it gives something back to you. The more powerful the subject, the more happens on the set.”

With “Dead Poets Society,” Weir says, “We’re dealing with creativity and the potential within us all: the possibility of enriching your life. That idea fueled the production; people were eager to go to work.”

On Christmas Eve, such was the congeniality of the company, some two dozen of the cast and crew appeared at Weir’s door, singing carols. He joined them and they marched on to serenade the cinematographer, John Seale.

Looking at the young actors, Weir was reminded of the freshness and optimism of the early Beatles and the sense he had of a new generation then and of a new one now. “My daughter’s generation. She’s 16 and she’s not affected by the ‘60s; she has her own ideas. She listens to the Beatles and concludes that they were the best. But it’s her decision, now. The old rock ‘n’ roll is better than the new rock ‘n’ roll, she thinks.

“The ideas from the ‘60s have been worked through. We’ve now become the Establishment. We need fresh thinking. Perhaps we’re now on the point of change. I love change; I’m thrilled by it. But I find some of my contemporaries as dogmatic as any of those we were angry about in the ‘60s.”

After “Mosquito Coast,” Weir took a year off, deliberately. “For 15 years I’d been shooting all over the place. I needed to sit still. The first six months were terribly difficult; I didn’t think I was going to make it. But the second six months there was a wonderful freeing up.”

He wrote a script with a specific actor--Gerard Depardieu--in mind, not knowing if Depardieu would like it or was available. He did but wasn’t, not for a year. Weir was heading back to Australia from meetings in Hollywood about the project, called “Green Card,” when Katzenberg gave him the script of “Dead Poets Society” to read on the flight home. He had dealt with Katzenberg on “Witness” while Katzenberg was still at Paramount and they had stayed in touch. (“Green Card,” with Depardieu working in English, will start shooting in January.)

“I don’t like to read on planes but the title was intriguing and I found myself reading it all. But I hardly thought I’d be doing it. People who’ve seen the film assume it must have begun as a novel, because there were so many layers in it. I tried to keep that sense of things going on at many levels.”

Schulman’s original script remained largely intact, although he visited the set and did some minor rewrites, and Robin Williams transformed some of the material to his own metier. But the part is notable for Williams’ understated blending of the very funny and the very serious.

“I don’t like the word ‘restraint,’ ” Weir says. “It was a very careful interpretation by Robin. We agreed we should work from the end to the beginning. At the end it’s got to be clear that the boys, and the audience, love the teacher (Keating). If it’s Robin Williams, not Keating they’re responding to, the ending will smell. We had to look for comedy that was subtle.”

A long classroom sequence that was hilarious but too far from character was dropped, Weir says, because it was too funny.

How does a film maker know that he’s succeeded, presuming that the answer may or may not be the one the box office gives him? “If a film works,” Weir says, “it has a longer multiple-screening life. I mean, you can stand to see it often at all those sneak previews because it offers you something provocative to think about.

“At some point at the end of filming, you match up the original inspiration that made you do the film against what you have. ‘Did I put on the screen what I intended to put on the screen?’ If the answer is ‘no,’ you’ve failed. If it’s ‘yes,’ the rest is all details.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.