For exactly one Saturday, in the summer of 1996, I stood on the corner of Sunset Blvd. and Ogden Dr. hawking maps to the movie stars’ homes. Earlier in the week, six of us, all immigrants from the former USSR, had been rounded up for the job by a Fagin-like fellow — stringy, squinty, coils of white hair sticking out like fried electrical cords from the back of his baseball cap. I don’t remember whether I had my mother sign a minor’s work permit or simply forged her signature, but I do remember that I sold exactly one map. Unforgettable too was the look of disgust on our Fagin’s face as he peeled a fiver off his soggy roll of bills at 5 pm: my salary. The pay was piddling, the task demeaning. There was little shade on the corner, and I was too easily wounded by the reactions of some of my potential customers, their rude sneers and pitying frowns. To this day I accept every flyer handed to me on the street with a smile, recalling my own unhappy turn as a peddler.

Sellers of star maps were ubiquitous during my early years in Hollywood, but something drove them off the streets in the 2000s. I suppose it was the double threat of the internet, which made celebrity addresses free and easy to find, and reality television, which fed viewers the illusion of round-the-clock access to certain celebrities’ private lives: why drive around in the hope of spotting a star in the distance when you can sit at home and watch them squabble in their own kitchens?

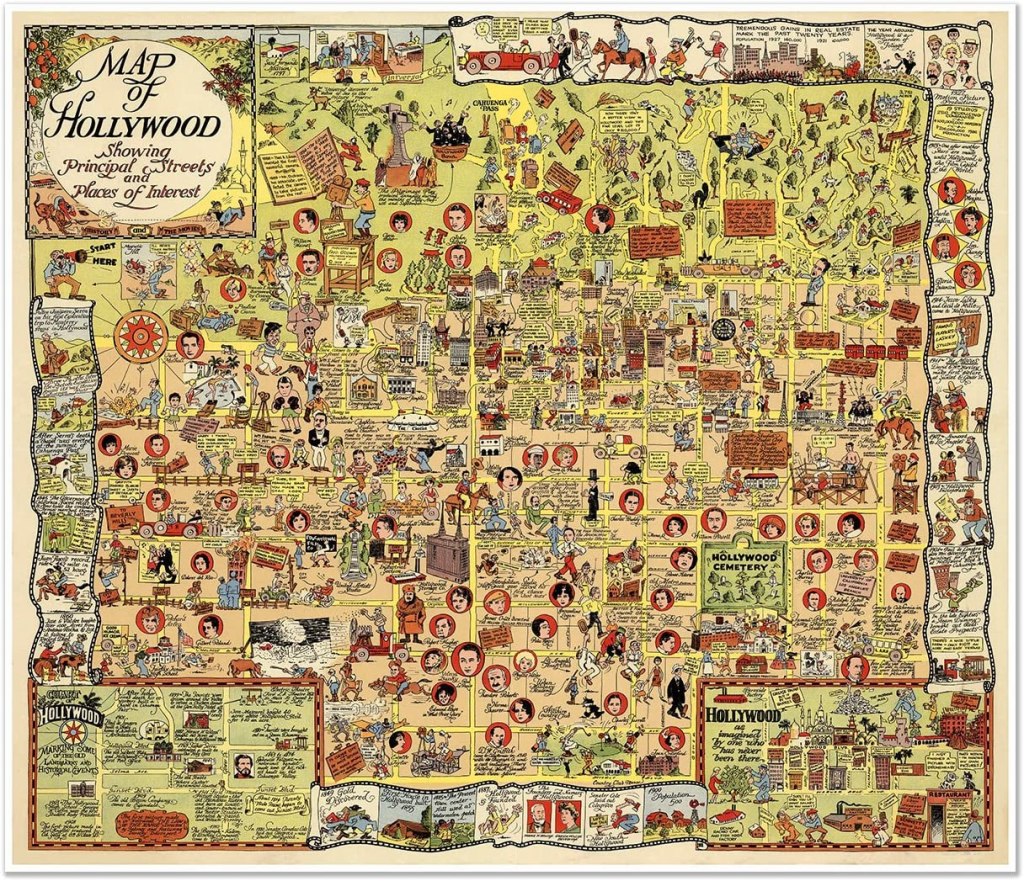

The notion of “Maps to the Stars” — so emblematic of LA that it lent a title to a fine satirical noir by David Cronenberg — is history now, but a history that remains largely unrecorded. I was surprised to discover, in college, that the trade dated back to the days of F. Scott Fitzgerald, who has his charmingly dissolute hack, Pat Hobby, take an ineffectual stab at it in a story from 1940, “The Homes of the Stars”:

Business was bad or Gus would not have hailed the unprosperous man who stood in the street beside a panting, steaming car, anxiously watching its efforts to cool.

“Hey fella,” said Gus, without much hope. “Wanna visit the homes of the stars?”

The red-rimmed eyes of the watcher turned from the automobile and looked superciliously upon Gus.

“I’m in pictures,” said the man, “I’m in ‘em myself.”

“Actor?”

“No. Writer.”

Pat Hobby turned back to his car, which was whistling like a peanut wagon. He had told the truth — or what was once the truth. Often in the old days his name had flashed on the screen for the few seconds allotted to authorship, but for the past five years his services had been less and less in demand.

Presently Gus Venske shut up shop for lunch by putting his folders and maps into a briefcase and walking off with it under his arm. As the sun grew hotter moment by moment, Pat Hobby took refuge under the faint protection of the umbrella and inspected a soiled folder which had been dropped by Mr. Venske. If Pat had not been down to his last fourteen cents he would have telephoned a garage for aid — as it was, he could only wait.

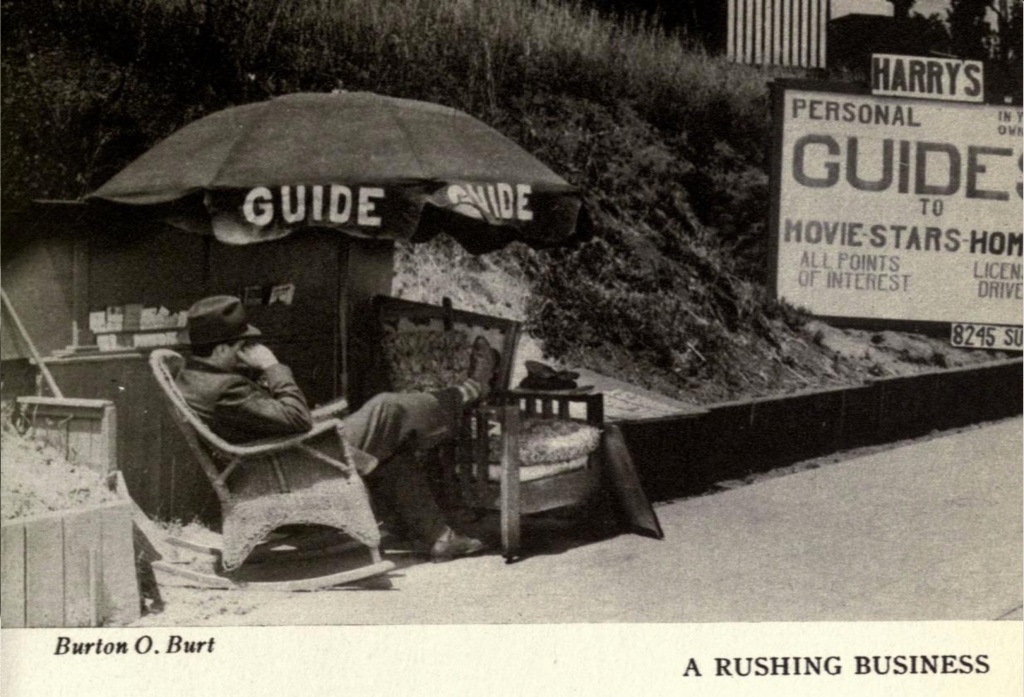

That umbrella stuck in my mind and popped up some years later when I ran across a photograph in the 1941 Works Progress Administration publication Los Angeles: A Guide to the City and Its Environs, which has since been reprinted by the UC Press with a superb introduction by David Kipen.

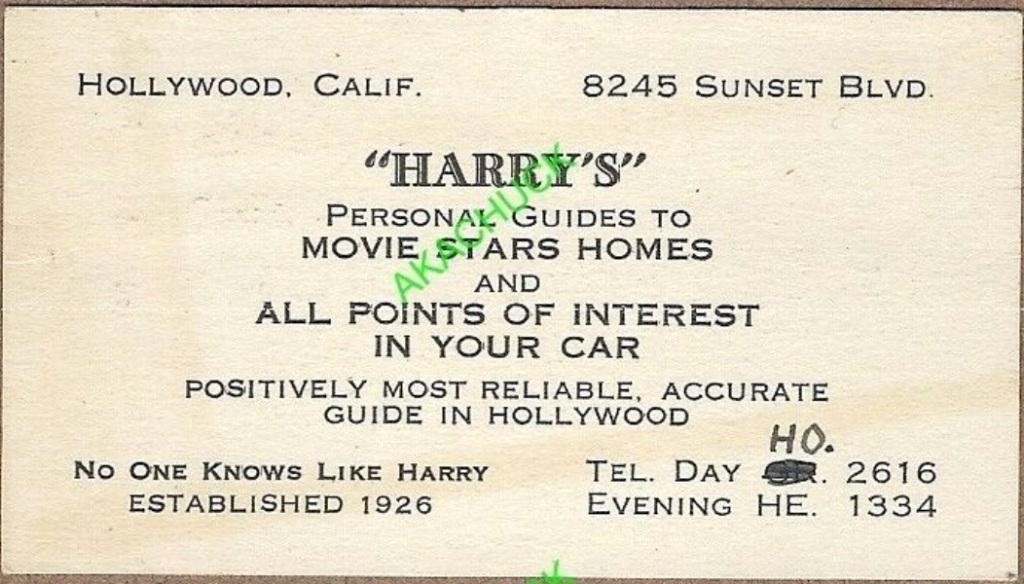

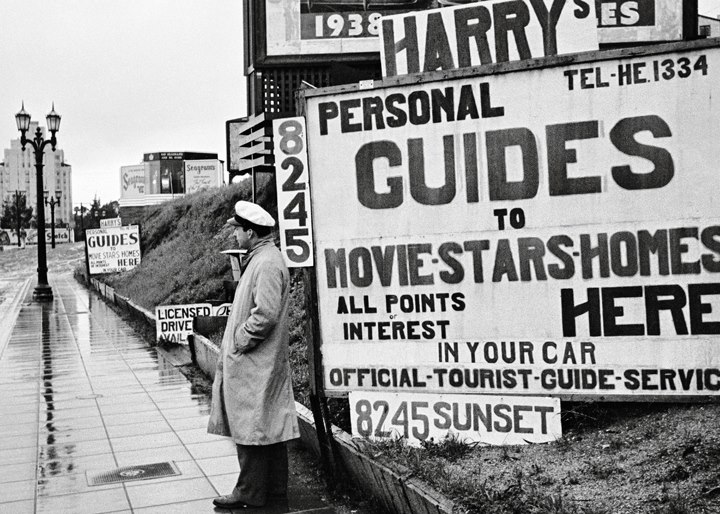

Well, I thought, if Fitzgerald’s Gus wasn’t modeled on this Harry, I’ll eat both their crumpled fedoras. But who was Harry, who appeared to have stationed himself right at the mouth of the Sunset Strip? From time to time I’d catch glimmers of this forgotten star of the star-map racket — a photo of him in the rain from 1937, and even, thanks to eBay, his business card.

It wasn’t until this past week, though, that I finally got to hear the man’s story, more or less from his own mouth. It came to me by way of Benjamin Appel, an unsung master of gritty crime fiction and the author of The People Talk (1940), an oral history of the Great Depression. One of the chapters in The People Talk is devoted to “Flickerland People,” and Appel’s first informant is none other than Harry. Describing his stand, Appel writes: “The signs are lettered in red, white and blue; Harry, himself, in the middle of them under a beach umbrella. His tanned shrewd face fits the amusement park atmosphere of this highway office, his blue suit, black bowtie and sun glasses exactly the right uniform.” Cutting to the chase, Appel asks: “How did you become Harry, the Guide?” Harry responds:

“That’s quite a number of years ago. I used to know a lot of Hollywood people. I used to be in the vodvil business myself, I’ve got a game leg.” He glances down at his feet. One of his shoes has been specially constructed. “I can’t get around like you other guys… Friends of mine used to ask me where the stars lived and I used to tell them. Now when they ask me, they pay me.” He leans back in his camp chair. “I was born back in Rhode Island… I’ve been all over the damn world. One time I had plenty of dough. Now I got nothing. I’ve had people here from all over the world. I’ve had from the highest to the lowest, people who had to scrape up the three bucks they paid me to see the stars’ homes. I’ve had men who when they come out of their car were in overalls.”

Harry — who didn’t just sell maps but actually accompanied customers on star safaris in their automobiles — has a lot more to say to Appel, but I got my answer from that passage. Here was the man who had started it all, a broken-down vaudevillian who found a precarious foothold on Sunset Blvd. And at some point he lost that foothold, ceding way to countless imitators — including me, for a day. He loiters on the edges of history, as he did on the edge of the road: in Depression-era guides, in a short story by Fitzgerald, and, just maybe, in Nathanael West’s masterpiece, The Day of the Locust (1939), in which an ill-fated old vaudevillian named Harry Greener goes door to door selling ersatz silver polish.

And what of his old spot? As far as I can tell 8245 Sunset Blvd. is now the parking lot of an overpriced Mexican restaurant. Someone ought to put up a plaque, or at least a pin on Google Maps.

All too poignant!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suspected it would pluck at your heartstrings, my friend!

LikeLike

I love this piece! It’s at the same sad, funny, poignant, and deeply human.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much! I’m so happy to know that I stuck the landing at that intersection, for which I’m always aiming.

LikeLike

So interesting Boris! And I can imagine one day at that kind of job would put you off for life… The history of Harry is fascinating, and I hadn’t realised the tours of the stars’ homes began so early (it’s a very long time since I read that Fitzgerald, so if I knew I have forgotten!) Interestingly, when we visited LA in my teens, we had a tour of the homes, but if I recall correctly it was in some kind of coach – such have times changed! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading and reminiscing, dear Kaggsy! And yes, I forgot to mention that the tour busses were still going before the lockdown, and may be back in operation now. The tabloid magazine TMZ seems to have a corner on that market.

LikeLiked by 2 people

What a great story! “Once I led the life of a millionaire…” But if you play your cards right, people do know you when you’re down and out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So glad you cottoned to Harry, LH! And you said it: whether you’re top of the heap or near the gutter, doesn’t hurt to be nice.

LikeLike