As Hong Kong enters its third month of mass anti-government protests, across the border in China, people are seeing a very different version of events.

On Saturday, as protests entered their tenth weekend and demonstrators and police clashed in Hong Kong, the People’s Daily posted an article on the Chinese WeChat webchat service saying members from “all parts of Hong Kong society” were calling for the “violence to stop”. As peaceful rallies at the Hong Kong airport continued over the weekend, Chinese state media posted videos on Weibo of a tussle between demonstrators and an angry resident yelling: “We just want Hong Kong to be safe”.

Other special reports include letters between the Chinese and Hong Kong police applauding “the great bravery” of the Hong Kong police – a main target of the protests. Last week, a journalist with state news agency Xinhua travelled to Hong Kong and described the city as “shrouded in black terror”.

Over the past two months, Chinese state media outlets have gone from near silence on the protests and blanket censorship of footage of the demonstrations to actively pushing news, editorials, videos and online discussions.

“On the topic of Hong Kong, the mainland media can’t be seen as journalism. It’s purely propaganda… It is intercepting a small part of the information, distorting it and magnifying it,” said Fang Kecheng, a professor at Chinese University of Hong Kong, specialising in communications.

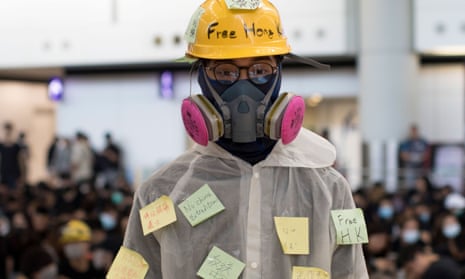

In Chinese state media the demonstrations, most of which have been peaceful, are routinely described as “riots”. Daily coverage show footage of protesters hurling bricks, jeering at police, and surrounding police stations. The protesters are described as “radicals” and “thugs” seeking to topple the entire system through independence for the city, a former British colony now under Chinese sovereignty.

Few protesters have been pushing for independence – their demands have included the permanent withdrawal of a controversial extradition bill and an independent investigation into police behaviour.

Taking a page from the protesters’ book, the People’s Daily published a range of posters, one featuring muscular riot police facing off against brick-throwing rioters. “It’s hard to say whether it is right or not to hit them,” the posters declare. “I only hate that they are also Chinese people.”

Protesters are also portrayed as “lured by the evil winds” of foreign agents. Chinese officials have accused the US and other western countries of being the “black hand” behind the protests – a narrative that pro-government figures and media in Hong Kong have also seized on.

Observers see the shift as a way to prepare the public for more drastic action Beijing or the Hong Kong government may take toward the protesters as well as a chance to push China’s view of events.

“The propaganda authorities perhaps realised this could be an opportunity,” said Fang. “There is not much to say when the marches are peaceful. But now with these violent incidents, the authorities can exaggerate them and stir Chinese people’s emotions. They can play into nationalist sentiment.”

That appears to be working. A discussion topic on Weibo hosted by the People’s Daily – titled “Protect Hong Kong, firmly say no to violence” – has more than 1 million comments, most in support and some calling for more extreme measures. A “protect the national flag” campaign on Weibo has been trending, after protesters in Hong Kong twice threw the Chinese flag into the sea.

Many mainland Chinese believe foreign agents are indeed behind the protests, a claim protesters and observers see as laughable.

“At the end of the day, Hong Kong is still part of China. What they are doing is pointless. The foreign countries pushed and they just followed,” said a student studying overseas in Seoul who asked not to be named.

“I don’t know their motivation is,” he admitted. “The news we receive is biased and only from one perspective.”

Few Chinese residents are clear on why the protests began in the first place. “I don’t know the details,” said Guo, 20, who lives in Beijing. “But I think we should be united and together and we should be patriotic. Only a united country can continue to develop stronger.”

Others also pointed to a lack of patriotism as the problem. “Maybe it’s the education system. If they were educated to be patriotic from an early age, it wouldn’t be the way it is now,” said Liu, 18, a recent high school graduate from Shandong province.

Observers say Chinese state media have purposefully obscured why the protesters have been demonstrating for the last two months, focusing instead on violent clashes between the protesters and police. Chinese state media have described armed men who have attacked commuters and protesters as “patriots”.

“Left out is reporting on and images of police violence, of which there has been a good deal and the attacks on unarmed protesters by armed thugs,” said Jeffrey Wasserstrom, a historian of modern China at the University of California, Irvine.

“The implication is that what protesters have been doing is creating ‘chaos’ or luan, a very freighted word in the People’s Republic of China,” he said, referring to the term’s usage to describe the upheavals of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s as well as to criticise protests in Tiananmen Square that were violently put down on 4 June 1989.

“This echo is worrying, even if it is always too simplistic to look for history repeating itself step by step in a different context,” he said.

Not everyone subscribes to the official media’s version of events. Images have circulated online of ID cards posted by Chinese netizens in support of the protesters.

A blogger on Weibo, who asked to identify herself only as Z, has been trying to share articles she believes show the real nature of what is happening in Hong Kong. Her posts are often deleted or blocked on Wechat or Weibo. An article she and her friends tried to circulate, with a timeline of events in Hong Kong and answers to questions about the protests, was blocked after receiving more than 100,000 views.

“The main reason why Hong Kong people are against the extradition bill is distrust of the mainland judicial system, so how could they let the 1.4 billion people of China see that?”

“I think all the actions that Hong Kong people took are reasonable and understandable. I feel sad and heartbroken,” she said.

She added: “As a citizen, it is common to protest against what you think is unreasonable. It’s just that this is not common here on the mainland.”