In 1986, during the confused final stages of the controversy involving Labor politician and high court judge Lionel Murphy, the Hawke cabinet opened a new inquiry into him, resolved to defend it despite its apparent zeal, then prematurely closed the inquiry and decided a fortnight before Murphy’s death to pay his considerable legal costs.

A release of cabinet documents from the National Archives confirms this much but reveals little more about the messy end of a two-year drama that inflamed passions and tested friendships in legal, political and media circles.

The Hawke cabinet not only decided to wind up its unusual parliamentary commission of inquiry into “various matters relating to the alleged conduct of Mr Justice Murphy”, it resolved “that material related to allegations obtained by the commission was never to be made public or be treated as being subject to the archives legislation”.

The few records about the Murphy saga that have been opened are brief cabinet decisions. All lack the written submissions that usually accompany a decision and give the background and pros and cons of the issue under discussion.

Frustrating as this may be for scholars and the partisans of the pro- and anti-Murphy camps, it is unsurprising. From the start the Murphy saga was murky.

In late 1983 and early 1984 Fairfax papers the National Times and the Age published reports based on tapes, transcripts and summaries of illegal telephone intercepts reportedly made by some New South Wales police. The authenticity and accuracy of the material were never proved. But the headlines it spawned, such as “Secret tapes of judge”, soon led to Lionel Murphy being named as the judge involved.

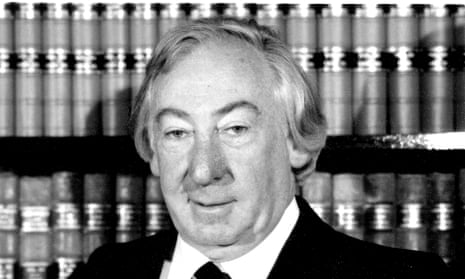

Murphy, the reformist attorney general in the Whitlam government, had been appointed to the high court not long before Whitlam’s dismissal by the governor general in 1975. Often in dissent, he had shaken up the court as he had earlier shaken up the Senate and the public service, particularly the security services.

At the core of the “Age tapes” controversy was whether there was evidence sufficient for parliament to remove Murphy as a high court judge because of what the constitution calls proved misbehaviour.

The core allegation was that Murphy had tried improperly to influence decision-making by a magistrate and a judge in a case involving a solicitor Murphy had known for many years, a solicitor who had represented a major organised crime figure. The line that became shorthand for the Murphy issue at the time, a line which Murphy denied having uttered, was the favour-seeking question: “And what about my little mate?”

The Hawke government watched on in anguish. Publicity about Murphy revived memories of the Whitlam years, a period the Hawke team had been keen for the public to forget. A taint of perceived corruption could spread. Some objected to what was happening out of principle or loyalty or a mix of both. The Labor party in the 1980s contained Murphy’s former colleagues and admirers as well as his enemies. Many were building on reforms which Murphy had initiated.

Over several months, two heavily publicised Senate committees grappled with a complicated mix of facts, inferences and conjecture. Murphy and his supporters strongly attacked the process. It denied him natural justice, they said. The attack on Murphy was an attack on judicial independence.

They raised a string of objections: that the origins of the material were unknown; most transcripts had no matching tapes and could have been fabricated; the intercepts had been illegal; the newspapers had distorted the material; incidents from Murphy’s social life with innocent explanations were being given false and sinister interpretations adverse to Murphy; and the Senate committee inquiries were a kind of political trial.

Opponents argued that continued public confidence in the judiciary in general, and the high court in particular, depended on Murphy resigning or being removed. Judges were to be judged by a higher standard.

Murphy took leave from his duties on the high court but refused to resign.

The second Senate committee found against him and Murphy was later charged with attempting to pervert the course of justice. In July 1985 he was convicted, but almost immediately members of the jury began to tell media outlets, a legal academic and Murphy’s solicitors that they did not believe Murphy was guilty. Their verdict had been reluctantly reached on the basis of misunderstood directions from the trial judge. An appeal was upheld, the conviction was quashed and at the second trial in April 1986 Murphy was acquitted.

Arrangements were made for Murphy to resume work at the high court on 1 May. Two of his fellow judges sent messages congratulating him on his acquittal, but not everyone at the high court was happy about Murphy’s imminent return.

Almost immediately, new claims about Murphy surfaced. The newly released archives give a glimpse of what happened next in cabinet. At the time, cabinet’s decisions dismayed Murphy supporters, who believed the saga should have ended with the acquittal. “Final codas of farce and tragedy,” one legal academic wrote later.

On 5 May the cabinet heard from the attorney general, Lionel Bowen, that the chief justice of the high court, Sir Harry Gibbs, had advised Bowen that Murphy had met that afternoon with his fellow judges and “it was agreed that he would voluntarily refrain from sitting on the high court until such time as he had an opportunity to answer all matters allegedly involving him”.

Murphy’s “statement by way of an answer” was to be “made available for consideration” to the high court, the attorney general, the opposition leader and leader of the then minor party the Australian Democrats. It reads like a very confidential sort of “mini trial” was envisaged to allow this select group to satisfy themselves about Murphy’s fitness to sit again among the other high court judges.

But two days later the stakes were raised. Cabinet decided to have Bowen tell parliament that it would legislate expeditiously for a “parliamentary commission of inquiry into various matters relating to the alleged conduct of Mr Justice Murphy” so that “proper consideration may be given to the question of possible misbehaviour”. The government, Bowen was to announce, “has had full regard to the necessity of the standing and integrity of the high court to be properly protected”.

By 24 June, cabinet was prepared to defend the constitutional validity of its parliamentary commission against a high court challenge from Murphy, a challenge which Murphy’s fellow judges would have had to determine had it proceeded. Cabinet seems to have been wary of the alacrity the three commissioners showed for their task. Were new lines of inquiry in the offing? The minute of the 24 June decision records that the commissioners had requested that Australian Federal Police officers be made available to “help them with their inquiries”. But Cabinet “was of the view that the commissioners themselves had the power to initiate investigations into a matter only where the allegation was supported by material which established or pointed to a prima facie case being established”.’

The next two documents in sequence, on 11 August and 18 August, record decisions to wind up the parliamentary commission without it having to report, and to stop its records becoming public, even through the archives all these years later.

What had changed? In July, Murphy had been diagnosed with cancer and had only a few months to live.

Over the objections of the chief justice, Murphy returned to sit on the bench on 1 August.

The documents show that on 9 October, cabinet decided to pay legal costs incurred by Murphy of $420,473.

On 21 October, the day on which his last two judgments were delivered, Murphy died.