Another day, another set of shocking headlines about allegations of historical child abuse and high-level coverups, this time a dossier being handed over by the Metropolitan police themselves to the Independent Police Complaints Commission to examine 14 allegations of Scotland Yard’s own complicity in the alleged coverup of a high-level paedophile ring.

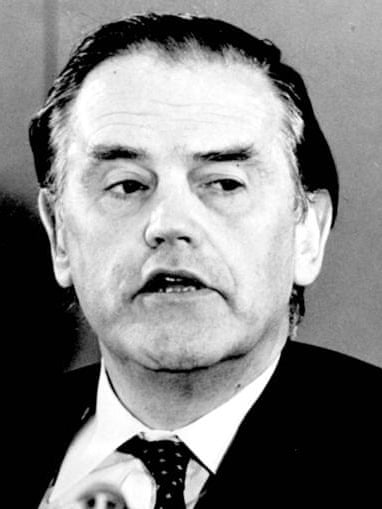

Two weeks ago it emerged that former MP Harvey Proctor’s grace-and-favour home in Belvoir Castle had been raided by police investigating historic allegations of child abuse. Proctor has denied any involvement in, or knowledge of, the alleged establishment abuse. Other claims fester. A raid was also made on the home of the former home secretary Leon Brittan.

All have denied charges levelled by alleged victims, some of them in files passed on by current MPs convinced of an extensive establishment coverup that lasted decades. But so did Cyril Smith, who got his knighthood in 1988 despite officials warning Margaret Thatcher of paedophile allegations against him, confirmed only after the former Liberal MP was dead. Freedom of Information (FoI) papers filled in fresh details this month. Smith is again central to today’s claims.

The allegations centering on Dolphin Square, a 7.5-acre, 1,250-flat complex by the Thames, include claims that boys in nearby Lambeth care homes were recruited as rent boys and ferried to the apartments for violent orgies where VIPs, defence and Whitehall officials, establishment types, as well as Tory MPs (one “cabinet minister”), were said to be participants. The Yard has spoken of “possible homicide” being committed. Historical and more recent allegations have been backed by Labour MP John Mann, who first encountered them as a Lambeth councillor in the 80s, but was told by police contacts that their inquiries had been stopped on orders from superiors.

How could it happen, politicians prominent in the 80s ask themselves? Were some of them mixed up in coverups, voters ask? So does the media, though it, too, has questions to answer. I was a Westminster political reporter at the time. I have been asking around.

This is a controversy with a long fuse. About 30 years ago, one of Margaret Thatcher’s junior ministers took me aside at Westminster and told me of serious allegations against a senior colleague. Since his version of events involved the abuse of other well-placed Tories’ children, it sounded pretty implausible to me. It still does, so I will not repeat it here, though both men are now dead and other versions of the same rumour have since surfaced.

With one borderline exception, it was the only such allegation that I heard as a working political journalist in the 1980s that was not also known to a wider public beyond Westminster. In the pre-Twitter era, such stories often surfaced via Private Eye, which picked up all sorts of gossip, some of which it concluded was untrue. Occasionally, a smear might be traced to security sources trying to damage someone, as may have been the case with my junior minister: a willing conduit for malice against a reforming minister who threatened vested interests?

As the Met’s Operation Midland ploughs through long-neglected allegations – the IPCC is now formally involved, too – and the New Zealand high court judge Lowell Goddard takes up the onerous chairmanship of the official inquiry, how do surviving politicians of the 70s and 80s react to what they are now reading? To allegations of politically powerful coverups, even of murder linked to Dolphin Square, where MPs have lived on weekdays for decades? Mostly with alarm and surprise, tinged with regret at their own naivety or complacency. Coverups? Perhaps one or two, concede a couple of people I spoke to. Among such sentiments from old stagers – MPs, ex-MPs, some now peers – and other veterans of Whitehall and Westminster, come admissions that they did hear – or read in the Eye – of shocking sexual allegations against some colleagues at the time.

They came to believe claims of a double life made against the then-Liberal leader Jeremy Thorpe. But they did not against some others since named – including Tory Peter Morrison, who was implicated in an abuse scandal centred on North Wales children’s homes, and even Cyril Smith. “A peculiar character, living with mum, but no one suggested anything else,” admits one avowedly naive Lib Dem colleague of the period.

In contrast to the sex-abuse cases that have rocked TV and showbusiness, no one actually saw anything. Most MPs are less worldly than celebs, Mrs Thatcher among them. A child of provincial Lincolnshire, raised in an austere Methodist household, what did she know about such things? A more clued-up figure would not have said, in praise of her deputy, Lord Whitelaw: “Every prime minister needs a Willie.”

Among more than a dozen old stagers I interviewed recently – most willing to speak only off the record – none recalls hearing anything about the now-notorious paedophile haunt Elm Guest House in Barnes, let alone about such crimes allegedly being committed at Dolphin Square – also part of the IPCC’s new inquiry. Up to 70 MPs lived in Dolphin Square, often without knowing their neighbours, fellow MPs included. “I only realised [a Tory colleague] had been living here for five years when I met him in the lift,” one recalls. “I thought it was where rich men parked ex-mistresses, old ladies with dogs,” says another former resident.

A common reaction to lurid gossip at the time, among political journalists as well as politicians, was that “It can’t be true – or someone would have been arrested.” Respectable provincial newspapers routinely protected readers from sordid tales. Tory ex-ministers with security experience also point out that “in those days the police were much more subservient to senior politicians. You did not get chief constables with minds of their own.” The police were more corrupt, too, some point out.

But, as in other recently uncovered scandals, the culture was different, too. One Conservative ex-MP recalls once being with Whitelaw, the ultimate old-school insider, when yet another “Tories and prostitutes” sex scandal broke in the Sunday papers. The reaction of the future home secretary and deputy prime minister was immediate. “Why has this been allowed to come out?” Whitelaw is now accused of demanding that police drop an investigation into the Westminster paedophile ring.

But widespread political coverups, even of a murder at Dolphin Square? “I don’t see how it would work,” says a former Labour chief whip. Whitehall was not wholly out of the loop. Robert Armstrong, Thatcher’s cabinet secretary from 1979 to 1987, tells me: “One got to know a certain amount about politicians’ sex lives, but I never heard a whisper about paedophilia.”

Officials such as Lord Armstrong were not wholly passive. As Edward Heath’s civil service adviser during his abortive Lib-Con coalition negotiations after losing the “who governs Britain?” election in 1974, Armstrong says the then-PM knew the rumours about Jeremy Thorpe’s private promiscuity. “Thorpe mentioned the possibility [of becoming home secretary in charge of security files], but that’s the last thing Heath would have offered him,” he now says.

Years later Armstrong gave Thatcher what he calls a “veiled” warning not to sanction Jimmy Savile’s knighthood for charitable work. She ignored it, as did David Steel in proposing Smith for a knighthood in 1998 despite known allegations against him by the alternative Rochdale Free Press, repeated in Private Eye. Armstrong’s successor, Robin (now Lord) Butler, flagged up concerns about Smith, we now know. So did the political honours scrutiny committee.

That Armstrong and Butler at least raised a problem may reassure the prominent Whitehall-watcher Professor Peter Hennessy. Journalist turned academic, now a peer, Hennessy remains astonished that a triple-lock defence line of security services, police special branch and the tax authorities did not tip off No 10 more effectively about dubious recipients of honours. But as a 1970s Westminster political correspondent, Hennessy too admits he shared widespread scepticism towards the Eye’s allegations against Smith and others.

Each case is different. Colleagues recall John Wakeham, Margaret Thatcher’s “Mr Fixit” and powerful chief whip in the mid-1980s, telling MPs who came to him with concerns about Morrison having cottaging skirmishes with the police: “If someone brings me some evidence I can do something about it, if required.” Wakeham would say years later: “I got no evidence at all.”

Morrison, scion of a wealthy Tory dynasty and MP for Chester, had powerful friends, including Thatcher, the defence of whose premiership he organised (disastrously) against Michael Heseltine’s challenge in 1990. The suspicion persists that, somewhere along the line, he was protected. “It never got out, but people said: ‘They’ll never be able to do that for Peter again,’” recalls one Tory. Morrison quit the Commons in 1992 and died in 1995, aged just 51.

“He was a very unhappy man and drank himself to death,” explains the former Tory cabinet minister and friend, who remembers being equally dismissive of unsavoury rumours about Cyril Smith. “I looked at Smith and thought, what an unlikely figure, that huge bulk and he could hardly walk properly.”

Evidence suppressed about Cyril Smith? Wakeham’s assumption today remains that the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) must have decided the evidence wasn’t good enough. This month’s FoI revelations confirmed that in 1970 the then-DPP did examine a Lancashire police file and concluded a conviction would be unlikely. Others say the problem was wider. This week’s claims on BBC Newsnight that officers were told to suppress their video evidence against Smith and forget it – on the orders of a senior colleague – suggests the critics are right.

Quite apart from the instinct to cover up rumours of abuse, another attitude was widely shared at the time by the press and public, too. “There was a universal desire to ignore it,’’ says another of the retired MPs interviewed. “We just didn’t understand it. It wasn’t deliberate neglect, more a lack of experience,” explains a Labour woman of cabinet rank. “Forty years ago attitudes were more relaxed,” explains Labour veteran and Old Etonian Tam Dalyell.

There were other significant features of the period. Though divorce was no longer a bar to elected office and homosexual behaviour between adults had been legal since 1967, it didn’t always feel that way: voters were less tolerant of MPs following them into the permissive society. Besides, people did not talk openly about private sexual behaviour, as they do now. Some MPs had affairs (women, including Barbara Castle, as well as men) and a few (Labour’s Tom Driberg, later Lord Bradwell) chased male members of the Commons staff. Driberg was protected by his old press patron, Lord Beaverbrook (much as Edward VIII’s love life had been) and by the security services. Most of it remained mere gossip.

Another factor different from today was solidarity. “There was a feeling at the time that you didn’t make trouble for other MPs,” recalls Dalyell, one of parliament’s great troublemakers for 40 years, but on political, not personal, matters. Dalyell shared the general distaste for Geoffrey Dickens, when the Tory populist made paedophile allegations – now being re-examined by police – in the 80s.

Suspecting Dickens of mere publicity-seeking, perhaps in collusion with a tabloid, he refused his appeal for help. “I’m much more concerned about our economic problems than this mire,” he recalls his admired ex-cabinet colleague Joel Barnett, a parliamentary neighbour of both Dickens and Cyril Smith, confiding at the time. Dickens, whose habit of mis-saying “fido-pilia” did not help his cause, was dismissed as a joke, though not all contemporary MPs discount claims that a senior home office official might have destroyed files. “That civil servant is a very bad man with nasty sexual habits,” one recalls being warned about one such.

Dickens was proved right in naming diplomat Sir Peter Hayman, later jailed. But suspicion of such boat-rocking MP colleagues lingers on, with eyebrows raised against the likes of Tom Watson, Simon Danczuk or John Mann, who have all campaigned for the investigation of abuse allegations. So does the hunch that some of the claims today by former victims may prove to be fantasy, exaggeration or revenge – “someone getting their own back”.

If the Westminster majority understood little about the gay world inhabited by some of their colleagues, paedophilia was a closed one. As the Daily Mail demonstrated in its campaign against Harriet Harman and Patricia Hewitt, two future cabinet ministers who worked at the National Council for Civil Liberties (now Liberty), the “anything goes” 70s tolerated a campaign that openly advocated consenting sexual relationships with children – the Paedophile Information Exchange – to affiliate to the NCCL before being discredited.

“We just didn’t understand,” ex-MPs now say. Just as women in all walks of life experienced bottom pinching (they knew which male colleagues were “not safe in taxis” ), unwelcome advances, and worse, so both sexes were what they call “more relaxed” about male acquaintances with an unhealthy interest in boys, girls or Commons secretaries. Society’s default position was to disbelieve complainants to the police. A northern Labour MP, now a peer (“I was so ugly the perverts didn’t fancy me”), recalls being spanked on his bare bottom by a teacher. But when his father offered to go to the police, his mother said: “We can’t do that, the man’s a priest.” Denials by those in authority were usually believed – the opposite of today.

Politicians of the day, beset with familiar problems such as economic growth, were fearful of delving into claims often made by those on the margins of society. They were wary of the twin Whitehall elephant traps known as “the can of worms” and “the slippery slope” that leads to who knows where. “Whatever you do, don’t go near the Kincora boy’s home scandal [in Belfast], it’s a can of worms from which you won’t escape,” one probing MP was warned only last year. He took the advice. But Kincora, too, is back in the headlines.

Ignorance, naivety, complacency and discretion, loyalty too, all are contributory explanations for decades of neglect. As the famous opening sentence of The Go-Between, LP Hartley’s novel of sexual intrigue, put it as long ago as 1953: “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion