It’s easy to make fun of The Lark Ascending. Perennially top of Classic FM’s Hall of Fame, it has become a byword for the conservatism of both schedulers and audiences. I’ve even written that lazy piece myself, unthinkingly dismissing the work as “bland”. So see this as a mea culpa: 100 years on from the first performance of the Lark, I have turned to a select band of internationally acclaimed violinists to ask them if the work deserves to be heard with fresh ears.

The piece was dedicated to and premiered by Marie Hall in Shirehampton Public Hall in Bristol on 15 December 1920. She and pianist Geoffrey Mendham performed Vaughan Williams’s arrangement for violin and piano; the version for violin and orchestra was premiered (by Hall) at London’s Queen’s Hall the following June. And it is in the same Bristol village hall exactly a century later that the British violinist Jennifer Pike will recreate the work’s first ever performance in a concert that will be streamed on 15 December.

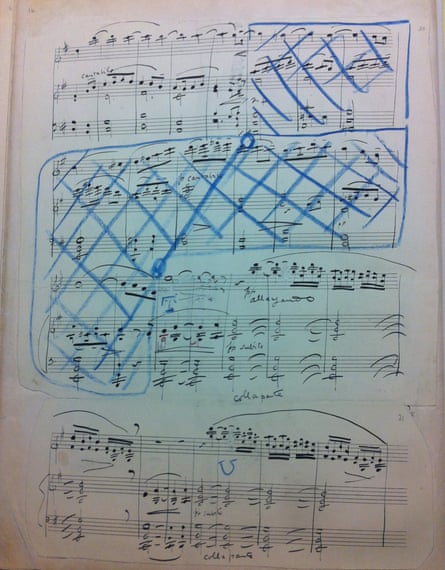

Vaughan Williams wrote the piece in 1914, probably originally in the orchestral version by which it became best known after 1921. But the war delayed the premiere and he revised it for violin and piano for the performance in Bristol, where Hall was staying with a wealthy patron. Pike believes the shadow of war hangs over the piece. “The closeness of the war and the tensions leading up to it have an effect,” she says. “Everything has unconsciously bled into this work – the sense of stillness, a yearning for peace, and Vaughan Williams’s love of the countryside.”

Richard King, in his 2019 book The Lark Ascending, links the piece with Vaughan Williams’s Pastoral Symphony, which reflected his experience of the western front. But the connection with the war, fuelled by stories of the composer being inspired to write the Lark after seeing ships on manoeuvres in 1914, is debatable. Writer and broadcaster Andrew Green, who has written about the genesis of the work in the latest issue of BBC Music Magazine, prefers to frame the composition in part as a response to the agricultural depression in England in the first 40 years of Vaughan Williams’s life. The chronology supports Green’s view.

The 15-minute work was inspired by George Meredith’s poem of the same name, written in 1881. “You don’t need to read the poem to enjoy the piece,” says Pike, “but that very simple concept of a bird flying free, soaring into limitless space, is a profound one that I do feel when I’m playing.” She says the passages for solo violin allow a freedom and almost improvisatory approach that other violinists also praise.

Pike was 15 when she first performed the piece, but had been suspicious of it at first. “I knew it was very popular, and at that time I rather naively thought to myself: ‘I don’t want to do anything that’s popular.’ That was a complete mistake because I came to realise what a sublime and forward-looking piece it is. Every performer can make it their own. No two violinists playing this piece sound the same.”

The US violinist Hilary Hahn has also known the Lark since her childhood – her mother loved the piece. “It was something I took as part of life’s landscape,” she says. “It didn’t occur to me that it stood for anything else than the piece itself.” Hahn recorded the Lark with Colin Davis and the London Symphony Orchestra in 2003, when she was in her mid-20s. Has her interpretation changed in the years since? “I trust myself more now,” she says. “I’m not as worried about whether I’m doing it right. I’m more intuitive in my playing.”

Some violinists tell me the piece is hard to play; others say not. What does Hahn think? “You have to be very comfortable with the instrument to give it the fluidity it needs,” she says. “You have to be comfortable with being expressive with a very slow bow. It goes high up on the violin and it has to be perfectly in tune, which stresses everyone out. It’s really important that your technique is refined and completely under control if you’re going to have any semblance of the freedom the piece needs. It’s like a duck: on the surface you’re just floating but underneath you’re paddling furiously.” The lark as duck.

Tasmin Little has long been associated with the Lark, recording it twice and playing it at the last night of the Proms in 1995. Does she find it melancholic or joyous, a representation of loss or a celebration of freedom? “Neither one nor the other,” she says. “You take from it what you want. It has a mesmeric quality that gives you space for reflection.”

She says there is a moment near the end where “the clouds have definitely arrived and crossed in front of the sun”, but she doesn’t find it sorrowful. The freewheeling, merrily singing lark simultaneously reminds us of the joy and possibility of life and, as it flies out of sight, of its transience. Little is about to retire from the concert platform and, appropriately, two of her final concerts later this month will feature the Lark.

Thomas Gould, leader of the Britten Sinfonia, recorded it with the Sinfonietta Riga in 2015 and has played it frequently in Albert Hall concerts aimed at a popular audience. “The key to its success is that audiences can just meditate,” he says. “They can lose themselves. It’s not a complicated piece. It doesn’t try too hard: it sets up a mood – one of meditation, calm and beauty – and it stays there.”

Australian violinist Richard Tognetti tells me he was inclined to dismiss it in the early part of his career as “a piece of English frippery”, and would pair it with Ligeti’s violin concerto. “That [programming] started off with a sense of irony,” he says, “but when I really listened to it I realised that The Lark Ascending was actually a radical piece.” He says it is not merely a lovely pastoral tone poem but a work that is “transcendental to the point where you are astral travelling”.

The Canadian violinist James Ehnes recorded it with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra in 2018. “It’s a piece that I first got to know in my teens and immediately fell in love with,” he says, “but in North America it’s usually assigned to the concertmaster [the leader of the orchestra’s first violins]. It’s rare that a soloist is brought in for the piece.” Outside the UK at least, the Lark is seen as too short to merit a soloist’s fee, and it’s cheaper to get the orchestra leader to play it instead, so Ehnes says he has had to fight for opportunities to perform it.

But the fight has been worth it. “I love the piece. It was a dream come true to record it. There’s a sense of nostalgia to the music, and nostalgia is an incredibly powerful and poignant emotion. It’s a piece that captures an atmosphere that is very specific but very difficult to define. That’s ultimately why music exists: to capture emotions that other artforms can’t express. If we could write it, we wouldn’t need the music.”

Jennifer Pike performs The Lark Ascending in a concert streamed from Shirehampton Public Hall at 7.30pm on 15 December. Also on 15 December, Janice Graham performs the work in an English Sinfonia lunchtime concert at St John’s Smith Square, London.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion