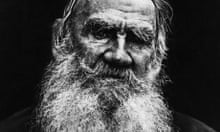

Philip Hensher

I do think he is the greatest novelist who ever lived. I didn't used to, but I have grown into him with age. When I was a boy I used to groan at the farming bits in Anna Karenina – now I could read about farming all day. Thee is so much in his work that you don't understand, but you feel that one day you might.

What is great about him is that he lets his characters grow up – they change, act totally out of character, and yet they are recognisably the same people. In War and Peace, Natasha starts out as a girl bouncing around quite happily, and at the end she is this grumpy matron who doesn't want to see anyone – yet somehow you believe it's the same person. I don't know how he does that. He does such rounded people.

War and Peace is the book that stays with you, but I also love his very late fables. There are two unforgettable ones: How Much Land Does a Man Need?, about the greed for land, and What Men Live By, a fable or fairy story where an angel comes down to earth. He attained this perfect simplicity of expression towards the end, and he grew out of the novel. I don't think anyone else has ever done that. You can learn more from Tolstoy than any other writer – but as a technician, not as a moralist.

Tom Keneally

Tolstoy is one of those annoying people of genius who performed in the 19th century the ultimate tricks that the rest of us are now stuck with trying to perform imperfectly and on humbler scale. In War and Peace, he successfully depicted the public and national soul as incarnated in a vast array of individuals, and the novel tries, in a compelling way, to define the same unity amongst his characters. In Anna Karenina, by contrast, he deals with one doomed soul on an intimate, psychological level. Thus he is a super-Balzac and a Flaubert at the same time.

Is he the greatest novelist of all time? I think Dostoevsky is a fellow giant. Fortunately, literature is not like the Premier League or the Olympic 400m. Let's just say that Tolstoy is transcendent, and that we are grateful he lived long enough to endow us with his grand inheritance.

AS Byatt

What is extraordinary about Tolstoy is the way in which his imagination was never daunted. His world is large, and his characters have their own life, and are not his puppets – even the ones he set out to disapprove of, such as Anna Karenina. His descriptions – of battlefields or mushroom-picking or meals – are full of exactly the right amount of idiosyncrasy and detail. He gives us more than enough information and still leaves space for the reader's imagination. He is the only writer I am not bothered by reading in translation: I don't notice what I might be missing as he sweeps me along. Celebrating him, we should also celebrate Constance Garnett, who changed the English novel and the English reader by translating the great Russians.

James Meek

JM Coetzee calls Tolstoy the exemplary master of authority, by which he means, I think, that he makes us trust what he tells us. This is all the more surprising since Tolstoy seems to speak freely, in his fiction, with the sort of moralistic-prophetic voice – the voice of a teacher of right and wrong – that lesser writers are obliged to use sparingly, unless they want to sound pompous and didactic. While that is distinctive and remarkable, it's not what makes Tolstoy a great writer. Nor is it his tight focus on the three essential themes in narrative art, namely love, death and money.

What makes him stand out is his skill with the very cloth from which narrative is cut – time. His fictional places are in time, not space. His descriptions of landscapes and interiors are never merely descriptions and never merely symbolic; they are waypoints in a journey, burdens to be got rid of, obstacles to be overcome, lessons to be taken.

More startlingly, he has the ability to do something that sounds easy but is in fact very difficult, namely to write about a moment – a man at the point of proposing marriage, a woman about to kill herself, a dissolute youth arriving in a frontier village – without any apparent consciousness of all the moments that have led up to that moment, or of all the moments that are about to come.

Great? Certainly. The greatest? Impossible to answer. One of the greatest literary craftsmen? Undoubtedly, and someone from whom today's writers can learn.

Ian Rankin

I put off reading Tolstoy for a long long time. But then, four or five years back, my wife and I went on holiday to Kenya. I knew I needed a big book to keep me going on the long flight, and plumped for War and Peace. I enjoyed the book, though I've never been a great fan of historical fiction. I did feel that he was happier writing about the haves than the have-nots, but he is a true general among novelists, marshalling his forces and always in control of the battlefield. Strangely, perhaps, I first came across him as a philosopher/non-fiction writer; I studied his writings on aesthetics at university. So I knew more about his life than about his novels. He has always seemed to me like a character from fiction himself – a tragic, complex personality. I get the feeling I will return to his novels as I get older, and will take more from them.

Marina Lewycka

I can still remember the first time I read War and Peace. I was 20, a student, and already had dreams of becoming a writer. I read it at a single sitting – about a week, including bleary breaks for eating and sleeping. There were times when the tears were pouring out of my eyes so much I couldn't focus on the tiny print. I felt proud to belong to the same culture (Ukrainian and Russian are very similar), but having Tolstoy as a model made it much harder to even dare put pen to paper.

Anna Karenina, which I loved too, was more manageable, if only because it is shorter and the narrative more focussed on an individual, but my all-time favourite is Resurrection. Its themes of social injustice and personal redemption resonated in the 70s, when I first read it. This, I thought, is what all books should be like: serious, committed and passionate. Maybe that is one of the reasons it took me so long to become an author. It is only when I gave up trying to emulate Tolstoy that I was able to discover my own voice as a writer.

Howard Jacobson

All novelists of any stature have this in common: they are engrossed by the apparent accidentality of life. "Things and characters go as nature takes them," Matthew Arnold wrote in an early appreciation of Tolstoy, "Levin's shirts were packed up, and he was late for his wedding in consequence . . . Serge was very near proposing, but did not. The author saw it all happening so – saw it, and therefore relates it." Arnold makes it sound easy. And indeed when we read Tolstoy, it feels easy. This is life itself. It barely feels like artistry. But it takes genius to make art so closely resemble life.

In Tolstoy's case this genius is the more remarkable for being at odds with other impulses in him – the impulse to preach, to teach, to reform: the impulse, in other words, not to be an artist at all. Anna Karenina set out to be a tract against adultery in high society; "Vengeance is mine and I will repay," is the epigram on the novel's title page. The voice of God. But Anna becomes a tragic heroine as a consequence of Tolstoy's "seeing" rather than judging her and relating what he sees. The novelist shuts out the moralist. To "see" Anna is to comprehend her. Later on, morality reasserts itself and Tolstoy regrets writing such trivia.

For my money, Tolstoy is the greater for these self-divisions. An artist ought to doubt the value of his art. The moralist needs to be in there somewhere, questioning the "seeing" and "relating", forever trying to sabotage the work, otherwise the surface charm takes over and we fall in love with narrative for its own sake. Art that is not in an argument with itself declines to entertainment. Tolstoy is the towering genius of the novel because in him the artist's sense of life's accidentality is forever challenged by the moraliser's drive to give life purpose.