In one scene in Cold Enough for Snow, the unnamed narrator explains to her mother why she likes Greek myths. They work like a camera obscura, she says, but for human nature: “By looking indirectly at the thing they wanted to focus on, they were sometimes able to see it even more clearly than with their own eyes.” What, exactly, our narrator might be focusing on animates this novella like a ghost.

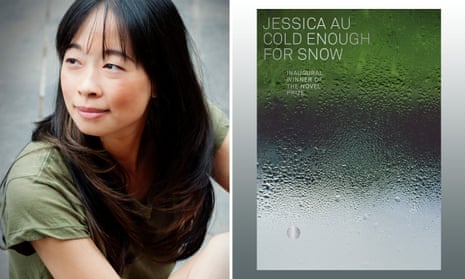

Cold Enough for Snow is the second book from Melbourne writer Jessica Au. It won her the first Novel prize in 2020 and comes a decade after her acclaimed debut, Cargo. The plot is simple; “deceptively” so, as some reviews have noted: mother and adult daughter visit Japan, see the sights, take in art and food, go home. What we hear of their conversation is quotidian and understated, at frustrating odds with the narrator’s pressing hunger for connection. Memories swirl of interactions with others: her partner Laurie, with whom she’s considering a child; the lecturer who introduced her to “the classics”; an unsettling customer at the Chinese restaurant where she once worked.

What links these apparently undirected reminiscences is a preoccupation with care. The narrator’s mother and uncle, born in Hong Kong, are “careful” in their gestures, take “care with [their] clothes and appearance”. She recalls her mother “perfectly repairing and adjusting” her childhood clothes; the objects “carefully chosen” in her lecturer’s home; Laurie “carefully measuring and planing back the wood” for his father’s studio. “Attention, taken to its highest degree,” as Simone Weil wrote, “is the same thing as prayer. It presupposes faith and love.”

Au’s calm, unrelenting focus would be hard to take over a longer book – but this novella is graceful and precise. Like the narrator fine-tuning the aperture on her Nikon camera, Au seems to say, we have to choose our scale, what we pay attention to. The narrator, hunting for deeper significance, is shadowed by the possibility this choice might just be random. She envies Laurie’s ability to “see things that others might miss”, and alerts herself to the “small details” in Japan’s subdued museums, bathhouses, bookshops. Glazed ceramics, fabrics, leaves, paintings: meaning floats to the surface, then scatters, as on rippling water. She takes her mother to an impressionist exhibition in Tokyo, full of “paths and gardens and ever-changing light, [showing] the world not as it was but some version of the world as it could be, suggestions and dreams.”

The two women peacefully make their way through shaded parks and forests, muted subways and shops. An older Japan – of villages, lanterns, temples – “halfway between a cliche and the truth”, shimmers through the “gentle rain”. In contrast, the narrator’s home in Australia seems soulless and overly bright, with its vast freeways, sprawling suburbs and screeching birds. The objects that stand out to her on the trip – a piece of jewellery, a photo, a bowl – betray her yearning for a more intimate scale.

What the narrator wants is ways to “know someone and to have them know me”. The trip seems obsessively planned around experiences that might spark some shared vocabulary with her mother, down to the time of evening that “might be nice” for a certain restaurant. A melancholy detachment seeps into all this perfect composure – an anxious sense of being outside the moment, not dissimilar to that seen in Katherine Brabon’s The Shut Ins, or Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies. Another, lost vocabulary hovers: her mother’s first language is Cantonese, hers is English – “we only ever spoke together in one”.

Cold Enough for Snow is filled with meticulous observation: temperature (“the subtropical feel, the smell of the steam and the tea and the rain”); colour (“a blue plate, the colour of agate, on which white flowers, probably lotuses, were painted, and … a mud-brown bowl, whose inside was the colour of eggshells”); light (as a rule, “milky”). The narrator reflects on the way she too is observed – by her lover as she falls asleep, in the way “one is able to look upon a person one knows well”. One way to know anything, perhaps the only way, is looking.

Finally, we bump up against what is not knowable. Au has mentioned her taste for “subverting narrative expectation … open endings, scenes in which nothing happens yet everything happens”. Cold Enough for Snow is exactly this, a book of inference and small mysteries. The stories, memories and images Au puts on the table escape easy conclusions – like the lines of a screen painting the narrator admires: “Some were strong and definite, while others bled and faded, giving the impression of vapour. And yet, when you looked, you saw something: mountains, dissolution, form and colour running forever downwards.” Aesthetic, opaque, endlessly uncoiling.

Cold Enough for Snow by Jessica Au is out now in Australia ($24.95, Giramondo), in US on 15 February (New Directions) and in the UK on 22 February (Fitzcarraldo).

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion