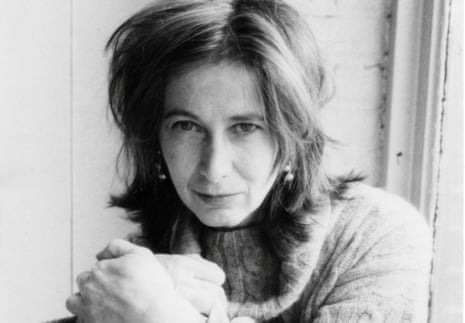

In 1997, Chris Kraus wrote that women’s written irrepressibility – the “sheer fact of women talking, being, paradoxical, inexplicable, flip, self-destructive but above all else public” – was the most revolutionary thing in the world. She added: “I could be years too late but epiphanies don’t always synchronise with style.”

As it transpired, she was 20 years early. Her first novel was so far ahead of its time that only now does its star seem to be approaching its apex, two decades after it was first published. With the proliferation of female voices today – a chorus she paved the way for – Kraus jokes: “Maybe there’s nothing less revolutionary.”

A barely-fictionalised account of a woman’s one-sided extramarital infatuation, I Love Dick was criticised as contemptible gossip in some corners of the art world upon its publication in 1997. The story unfolds almost entirely in letters from “Chris Kraus” to “Dick ______”: some sent, some not, and some written with input from her then-husband, the cultural theorist Sylvère Lotringer.

As both those relationships deteriorate, Chris’ letters become far-reaching essays, with Dick an increasingly peripheral presence in her own contemplations of art, sexuality and politics. But on publication, her radical antiheroine was secondary to speculation over the husband and wife’s perverse creative collaboration and Dick’s identity, later confirmed as the British critic Dick Hebdige.

It is really only in the last five years that Kraus’ “female loser” has been accommodated by the zeitgeist, and her own profile has skyrocketed with it. She is credited as a consultant on Jill Soloway’s television adaptation of I Love Dick, just released on Amazon Video to critical acclaim. The eight-part series, starring Kathryn Hahn and Kevin Bacon, is set in the present day and expands the world of the book to incorporate its legacy and its ardent following of what its author describes as “too-smart girls”.

This article includes content hosted on assets.tumblr.com. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as the provider may be using cookies and other technologies. To view this content, click 'Allow and continue'.

“In a way, the readership looks after itself,” says Kraus, speaking in Sydney ahead of appearances in the city’s writers festival. A fan-made zine was created, she says somewhat bemusedly, titled Kiss Me, Rape Me, Fuck Me: Letters to Chris Kraus. “The book creates a community of young women that doesn’t really need me – it’s a great thing.”

Kraus was 39 years old and a self-described failed experimental filmmaker when she met Hebdige, an acquaintance of Lotringer’s, in December 1994. Today she describes it as a “stupid sexual infatuation”, as much in response to Hebdige’s access to the art world and his ease within it as anything unique to his person.

“It was something about this kind of outsider, intellectual cachet that he carried around with him that was just a trigger for everything that I once thought I wanted, but didn’t have,” Kraus says.

“You’ve read Foucault, right? ‘Pouvoir-savoir’. That’s it: that’s the basis of many crushes, is that the person seems to have – has, maybe, power and knowledge that you want.”

She gives a one-shoulder shrug. “And so, what better way to get it?”

But did she get it? Yes and no, she says. “People acted when I wrote the book as if it had just appeared on my pillow because I slept with Dick – like I didn’t have to do anything at all.”Kraus moved past her crush by immortalising it. I Love Dick was written “in a delirium” in 1997, with her one-sided correspondence appearing more or less exactly as she wrote it in the throes of her thrall to Hebdige. “It’s not a repeatable experience.” (And certainly not in modern times: “We have email and it would have been over within two days.”)

She imagined the book as part romantic comedy, part “anthropological case study” of adolescent infatuation as experienced and articulated by a middle-aged woman. “I turned myself into a lab rat,” she said in an interview coinciding with its reprint in 2006. “I was very naive.”

In an early letter to Dick, Chris referenced Søren Kierkegaard’s concept of the “Third Remove” – that “art involves reaching through some distance”. In this case, to quote cultural theorist Joan Hawkins’ afterword, it is to a “fictional territory where adolescent obsession and middle-aged perversity overlap and intersect”.

The self-reflexive irony with which Kraus herself had enacted and experienced her infatuation (“the Crush, when will he call me?”, to quote that 2006 interview) was lost on many in print, with I Love Dick widely perceived as a salacious tell-all. Artforum said in its review it was “a book not so much written as secreted”.

Kraus points to William S Burroughs’ 1985 introduction to his novel Queer, in which he tries to explain his motivations for chronicling “unpleasant and lacerating memories” of his own romantic obsession:

While it was I who wrote Junky, I feel that I was being written in Queer. I was also taking pains to ensure further writing, so as to set the record straight: writing as inoculation. ... So I achieved some immunity from further perilous ventures along these lines by writing my experience down.

“I would say that was a similar experience with I Love Dick,” says Kraus. “I certainly never did that again, never would.”

But one central question remained unaddressed in I Love Dick: what would drive a couple to do such a thing?

Kraus’ relationship with Lotringer – the founder of the independent press Semiotext(e), which he now coedits with Kraus and Hedi El Kholti – looms larger in Torpor, her third novel. Published nine years later, it is the prequel to I Love Dick, with Sylvère and Chris reimagined as Jerome and Sylvie, on a road trip through Romania in the summer of 1991. Jerome is humouring Sylvie in her specious plan of adopting an orphan for the chance to take a last look at former eastern Europe before it changes forever.

As with I Love Dick, all the facts are true, says Kraus. “What makes something fiction isn’t whether it’s true or not – it’s whether it’s bracketed in time, how it’s treated and edited, and whether it’s construed as a work of fiction.

“I wasn’t able to use our real character names because that would have made it too personal, in a way that I wouldn’t have been able to write it.”

Torpor is a darker novel, as Jerome’s historical trauma of being a “hidden child” in the second world war (one of the Jewish children protected by Gentiles during the deportation) collides with the crisis in some countries of the former east at the start of the “new world order”.

“There were clearly going to be winners and losers, and Romania was definitely coming out a loser,” says Kraus. “It was a desperate situation.”

Torpor is about to be republished in the UK, with the new edition labouring to connect it with Kraus’ “cult super-hit” (“If I Love Dick is the book of your 20s, Torpor is the book of your 30s”). Kraus herself is leery of drawing too heavy a through-line across her work. With four novels and a few works of cultural criticism published in 20 years, she is not a prolific author; each book and “the place, the position, the voice to write it from” takes time to find.

Her upcoming “literary biography” of the experimental writer and filmmaker Kathy Acker has been in the works since Acker’s death in 1997. True to form, Kraus says it is more of a revisionist history than it is “one of those cradle-to-grave doorstopper books”, taking into account her own relationship with Acker.

Though she good-humouredly rejects the poet Eileen Myles’ statement that Kraus was “entirely obsessed … wanting to be Kathy”, Kraus concedes: “She was definitely a spectre and force in my life.”

The works Acker self-published in the early 1970s, when Kraus was in her late teens and living in New Zealand, had a particular impact. Kraus describes them in the same tones used by I Love Dick’s fans today. “They were those books that kind of just go straight to your heart, where it feels like the person’s voice is in your head and speaking for you.”

When Kraus moved to New York in 1976, aged 21, her path crossed with Acker’s – “But we weren’t friends and I wasn’t really part of her crowd.”

In the early 1980s, Acker moved to London, where she became “a genuine starlet”, to quote a Guardian write-up of a 2007 retrospective. Kraus says she found her work from that period “unreadable”, with the humour of Acker’s early books switched for something more sombre, essentialist, pornographic.

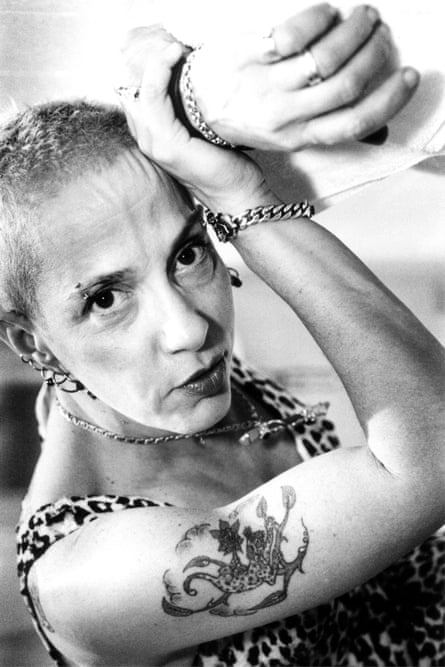

“Those absurd photos of her with the tattoos, and the underwear – they were really cool at the time, but I think after she died it took a long time for people to disassociate her work from that image,” she says.

“It just became embarrassing and dated – like thinking about your parents having sex … I kind of lost the drift there.”

In After Kathy Acker, to be published in the US by MIT Press in September, Kraus argues that Acker may have been the only female writer to successfully assume the role of “great writer as cultural hero” – and to also outlive it. Acker died of cancer at an alternative clinic in Tijuana when she was 50 years old.

Her life was “so sad”, says Kraus. “But she was also a terrible person, so it’s not as if she was a victim. Over and over again, she’d talk about this longing for community – but any time she was close to being part of one, she would sleep with everybody’s boyfriend, she would sabotage other people’s work.”

At a time when women were generally supportive of one another, Acker had internalised the idea “that idea there can only be one, and it’s going to be me”, Kraus says.

Acker was also Lotringer’s most recent serious ex-girlfriend at the time he got together with Kraus. In I Love Dick, Chris recalls reading inscribed in one of his books, “To Sylvère, The Best Fuck In The World (At Least To My Knowledge) Love, Kathy Acker”, and realising she was “up against some pretty stiff competition”.

Kraus had admired this author, been influenced by her work long before they crossed paths. In the spirit of pouvoir-savoir and all that, to what extent did Lotringer’s connection to Acker factor into Kraus’ desire for him?

She is momentarily thrown. “Well, I mean – Sylvère had a lot of other qualities besides being an ex-boyfriend of Kathy’s.” And she laughs.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion