I was prepared, I admit, to dislike Jeremy Hutchinson on principle. Here is a man whose life has been an exercise in clannish, well-connected endogamy. His mother was a Strachey, so as a child he was dandled by the grandees of the Bloomsbury group. At Oxford he fell in love with a Bonham Carter, while his sister sagely married a Rothschild. Hutchinson’s first wife was the actress Peggy Ashcroft; his second had been previously courted – not very ardently, I imagine – by Cecil Beaton and Edward Heath. He spent the war on a destroyer commanded by Lord Mountbatten, and when it was sunk David Lean’s film In Which We Serve turned the defeat into a triumph for patrician stoicism.

Inherited advantages were topped up by windfalls. A friend who died left Hutchinson a Monet; 10 minutes after taking delivery of the canvas, he sold it in Mayfair and snapped up a house in Hampstead with the proceeds. He currently lives in Sussex, in a former rectory of “magical beauty” which he paid for by disposing of an island he just happened to own in the backwaters of unbeautiful Essex. A tree in his garden was a gift from Leonard Woolf. And to add to his offences against the humble human average, he has survived, physically hale and intellectually acute, to the age of 100.

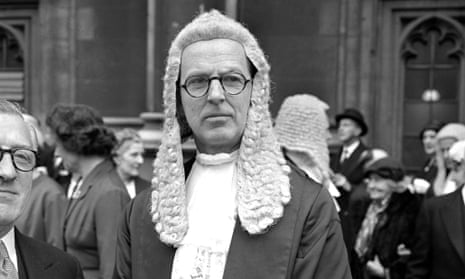

Given my automatic animus, you can imagine how confusing it was to be charmed into surrender by Thomas Grant’s traversal of Hutchinson’s long career as a QC. Yes, after being awarded a life peerage he did attack Tony Blair’s ban on fox hunting in a House of Lords debate, defending the civil liberties of the red-coated marauders and ignoring the panic and torment of the foxes they chased. But he had made amends for this, I discovered, by his act of class treachery in standing as a Labour candidate for the unwinnable parliamentary seat of Westminster in 1945: the teenaged Tony Benn drove his loudspeaker van, and Hutchinson swaggered up Downing St to canvass Churchill at No 10. And in later decades he eloquently supported the sacrificial victims of the establishment, who were put on trial for offences against British hypocrisy or for contravening the absurd official taboos of a secret state.

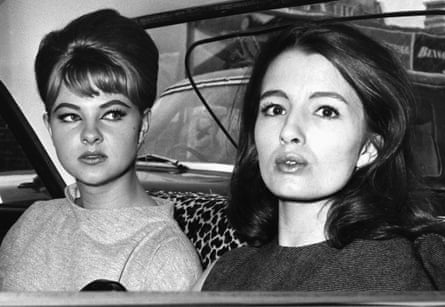

Sometimes he defended the indefensible. The spies George Blake and John Vassall confessed their guilt; Hutchinson could only plead in mitigation of their crimes. He volunteered to do so because he respected the religious force of Blake’s conversion to communism and pitied the gullible Vassall, blackmailed after a gay orgy in Moscow. He commiserated as well with the casualties of the Profumo scandal. Christine Keeler seemed to Hutchinson a blank-faced, passive weakling not a seasoned harlot, and he knew that Stephen Ward, vilified in the tabloids as a “whore-master”, was at worst a louche philanderer.

The clients Hutchinson cherished most were amiable rogues, Robin Hoods who prosecuted class warfare on his behalf. A retired Newcastle bus driver called Kempton Bunton – his first name commemorated a big win by his father at the eponymous racetrack – stole a Goya portrait from the National Gallery, then left it in a locker at Birmingham New Street station. The plodding police couldn’t catch him, so he turned himself in, and returned the loot, and explained the reasons for his crime: he believed that the £140,000 spent on the painting should have subsidised free television licences for OAPs. He was jailed for three months; apparently his son – thinner, nimbler, and better able to wriggle through a lavatory window in the Gallery – had carried out the robbery, but the quixotic Bunton did the stretch on his offspring’s behalf.

Hutchinson admired the dotty anarchism of the art forger Tom Keating, who put his fakes into circulation to unsettle the inflationary art market. Keating hated money, and was embarrassed when his fraudulent Samuel Palmers returned a profit; he treated himself to a moped, then squared it with his conscience by doubling the wages of his char lady.

Hutchinson’s most notorious scapegrace was the drug smuggler Howard Marks, whose effrontery made him “an anti-establishment folk hero”. Marks fantastically claimed that he had been working undercover for MI6 to infiltrate the IRA; Hutchinson called that defence “ridiculous”, but effectively ridiculed the blundering customs officers he cross-examined. One of them said he had peeped through a keyhole at the Dorchester and spotted Marks confabulating with some fellow drug runners. “Ah, so you recognised him by his knees,” drawled Hutchinson.

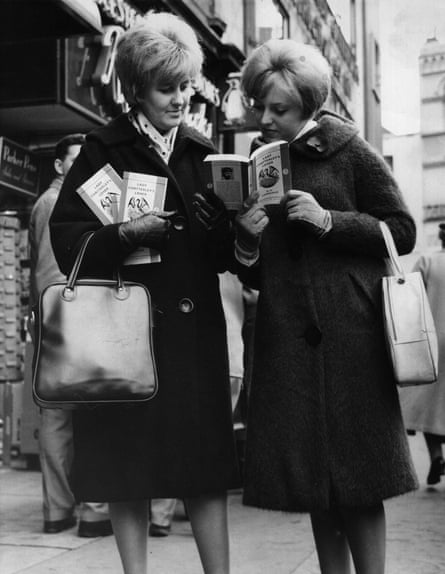

The triumphs of Hutchinson’s career were a series of obscenity trials, “moral dramas” – as Grant calls them – that altered the law and relaxed the manners of a stuffy, falsely pious society. He held the prosecution up to scorn in the Lady Chatterley’s Lover case, and reduced the judge to glaring at the members of the jury in a frustrated rage when they acquitted Penguin Books. After this, Hutchinson established that Fanny Hill was a harmless romp; he went on to demonstrate that a muddled, well-meaning tract on oral sex was unlikely to cause an outbreak of decadence and degeneracy.

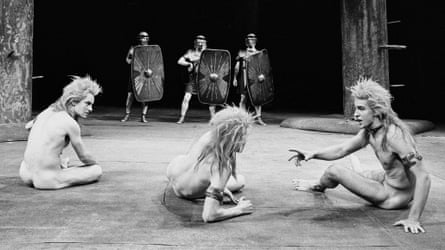

By the time he defended the National Theatre’s production of The Romans in Britain (in 1980), which included a simulated (and politically symbolic) act of buggery, he was confident enough to win the argument with some literal legerdemain. How, he demanded, could a witness in a cheap seat far from the stage be sure that he’d seen an erect penis in the vicinity of Greg Hicks’s bare buttocks? To illustrate his point, he concealed his hand inside his gown and let a balled fist and a thrusting thumb protrude at groin level. The case was subsequently laughed out of court.

In an impassioned postscript to Grant’s narrative, Hutchinson defines advocacy as “the art of persuasive and attractive speech”. What matters is that the speech should be attractive, and if possible amusing; above all it should persuade, even if it does so by learned quibbling. When Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris was prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act, Hutchinson got it off by contending with brilliant silliness that, since prints were delivered to cinemas in closed canisters, the film had not actually been published.

Niggling doubts remain. I’m left wondering whether trials are merely games. We trust jurors to determine what’s right and wrong: should they be wooed with such silken finesse by the histrionics of eloquent QCs? Hutchinson exonerated Christine Keeler by defaming Stephen Ward as “a perverted Professor Higgins”. It was a low blow and a specious point, but he had a job to do and was being very well paid. Advocacy is a performing art, and justice may not have much to do with truth.

Jeremy Hutchinson’s Case Histories by Thomas Grant is published by John Murray (£25). Click here to buy it for £20. Jeremy Hutchinson will be in conversation with Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger on Monday 8 June, 7-8.30pm, Kings Place, London N1

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion