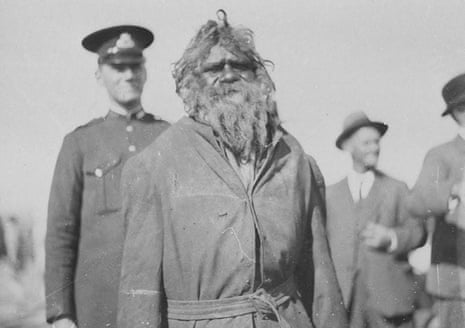

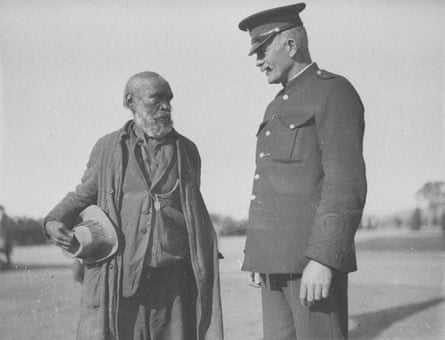

Two old blackfellas, Jimmy Clements and John Noble, made a big effort to turn up for the opening of the provisional parliament house in Canberra nine decades ago.

But, for 50 or 60 years, many historians seemed to think – despite their very different appearances, the photographs of them together, separately and with their dogs – that Clements and Noble might have been the same old bloke.

That, of course, gives us a window on to the white stereotyping of Indigenous people at a time when Australia believed it was – due to massacres, disease and assimilationism – witnessing the “vanishment of the race”. And it is instructive, almost 90 years to the day later, as Australia prepares to mark the 50th anniversary of the 1967 citizenship referendum, just how much – or little – has really changed.

The Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House has marked the 90th anniversary with a special exhibition, featuring research by its historian Stephanie Pfennigwerth, on the two Indigenous men. Clements (Nangar or Yangar) and Noble were Wiradjuri men from southern New South Wales, both aged about 80.

Each walked at least 150km to the Federal Capital Territory before the arrival of the Duke and Duchess of York (later King George VI and Queen Elizabeth), who formally opened the new federal parliament on 9 May 1927.

They were well-known throughout New South Wales and the capital territory.

Non-Indigenous people knew Clements as “King Billy”, consistent with the condescending settler tradition of bestowing royal title upon blackfellas they considered compliant, important, peaceful or useful. He was a respected elder and Lore man – a “clever man” – who performed Wiradjuri “burbong” (initiation), and a showman with the boomerang and spear.

Noble, also a clever man, was, like Clements, a renowned performer at country shows and football matches with boomerangs. He liked to say things were “marvellous”.

While the predominant media trope of the day was that an Aboriginal man had wandered, dishevelled and dusty, into the official opening celebration on 9 April and through the royal meet and greet on the 10th, the Wiradjuri and many contemporary Indigenous activists believe their actions were part of a calculated protest.

The Indigenous interloper was portrayed as something of a tragicomic figure as the police tried to evict him.

Regarding the events of 9 May, the Argus recorded an “old and grey and ruggedly picturesque” Aboriginal man was “determined to go his own way in spite of the arguments of two inspectors and one sergeant of police”.

“Immediately and instinctively the crowd in the stands rallied to his side. There were choruses of advice and encouragement for him to do as he pleased. A well-known clergyman stood up and called out that the Aborigine had a better right than any man present to a place on the steps of the house of parliament … The old man’s persistence and the sympathy of the crowd won him an excellent position and also a shower of small change that must have amounted to 30/ or 40/.”

Both Clements and Noble were photographed on 9 and, or, 10 April 1927 in interactions with police, who were, there can be little doubt – given the prevalence of segregation and mission-isation and the absence of almost any Indigenous civil rights – urging them to move on.

The next day one of the men, most likely Clements, had brief contact with the royals as the public paraded past them in front of the newly inaugurated building.

According to the Sydney Morning Herald, it was “Marvellous, the uncrowned king of Queanbeyan” who “aroused the amused interest of the duke and duchess and the waiting crowd”.

“His beaming black countenance was almost hidden beneath a shock of hair and beard. Barefooted and carrying a sugar bag in one hand and a tiny Australian flag in the other, he at first mistook a policeman at the foot of the steps for the duke. To his great embarrassment, and to the vast amusement of the onlookers, the policeman became the object of a hearty salutation. However, ‘Marvellous’ was quickly shepherded back to a position in the procession and, as he passed along, brought his hand up to an approved military salute for the benefit of their royal highnesses. The duke returned it with a special wave.”

Perhaps the Argus – which described him as “an ancient Aborigine, who calls himself King Billy and who claims sovereign rights to the Federal Capital Territory” – spoke to the Indigenous man involved.

Why else would the newspaper, not especially conversant with Indigenous rights, imbue his presence at the opening with such political significance had Clements (with his strong familial connections to the Ngambri and Ngunnawal, both of which claim custodianship of the Limestone Plains upon which Canberra is imposed) not, at some point, asserted Aboriginal sovereignty?

A few days later the Canberra Times – again with an emphasis on Indigenous connection to country – reported: “Where his dusky forebears have gathered in native ceremonial for centuries past, a lone representative of a fast diminishing race saluted visiting royalty. Despite the grotesque garb and untamed mane, the Aborigine comported himself not without dignity. With his three faithful dogs, he made an immediate target for a battery of cameras.”

Noble has shorter hair and a more closely cropped beard. This certainly describes Clements and paints a man whose act was performative – letting it be known sovereignty was never ceded, eyeballing the duke and courting of media attention.

The National Archives of Australia describes it as “possibly the first recorded instance of Aboriginal protest at Parliament House in Canberra”. It was the precursor to so much activism – from the 1938 Day of Mourning, the fight for recognition and much else in 1967, and the ongoing battle for land rights that manifested with the enduring tent embassy, just across the road, on Australia Day 1972.

The sign out front reads: Sovereignty never ceded.

Monash University’s Maryrose Casey wrote of Clements and Noble in the International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies: “Regardless of whether they were as unaware or indifferent to the meaning of the event, as is often suggested, their presence was a powerful act, contesting claims of the erasure of Indigenous people from the land and place.

“The same newspapers that for months had carried articles about the dawning of a new era for White Australia, all featured photos and reports of Clements claiming rights and sovereignty.”

This was, in my view, a critically overlooked subtext to an eventful couple of days surrounding the opening of a building that remains one of the most publicly identifiable in Australia – a place that quakes with history and is filled with ghosts and stories that today is home to the Museum of Australian Democracy.

The duke, a nervous speaker who stuttered terribly (remember The King’s Speech?), secretly practised his words the evening before; an airforce flyover – during which one of the planes crashed, killing the pilot, where the National Library today stands – drowned out his stilted oratory and Dame Nellie Melba’s national anthem; a locksmith spent an hour oiling the lock to the house which the duke would open with a special gold key so that he did not in his nervousness break it off in the chamber. The event was so over-catered (perhaps 30,000 of an anticipated 80,000 people turned up) that tons of pies, sausage rolls, fish and prawns had to be buried.

The historians reckon the food was buried at the Queanbeyan tip. But some of the old timers of the Limestone Plains used to say it was all buried just a stone’s throw from Old Parliament House, on what is, today, the foundation of the finance department.

All that excess in the ground under Finance is, of course, an irresistible metaphor as Old Parliament House prepares to turn 90 next Tuesday – federal budget day.