The health minister Greg Hunt has asked for an urgent briefing about the clinical trial of a decades-old drug in the prevention of Covid-19, as countries race to find a way to prevent serious cases and slow the spread.

But infectious disease experts have warned the drug, hydroxychloroquine, is far from proven as effective in treating Covid-19 and that it could take several months for results to be conclusive. In previous studies for other conditions, hydroxychloroquine has been shown to cause heart damage and toxicity.

On Tuesday Hunt spoke about government support for two trials involving hydroxychloroquine, which is an anti-malarial drug also used to treat autoimmune conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.

The first trial, announced one week ago and being conducted by the University of Queensland, is looking at whether a hydroxychloroquine and an HIV drug used either in combination or on their own can reduce severity and length of Covid-19 if given to patients with the virus early after diagnosis.

The second trial, being conducted by Melbourne’s Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and which Hunt said had “the potential for possible prevention” of the virus, will focus on giving 2,250 health workers around Australia hydroxychloroquine preemptively before and while they are exposed to patients with the virus. Researchers want to see if health workers taking the drug for four months are prevented from getting it.

Infectious disease physician Prof Marc Pellegrini is leading that study and said health workers were at the frontline of treating the virus so any preventative drugs would be valuable.

While hydroxychloroquine is effective for treating autoimmune conditions, Pellegrini said researchers were not sure exactly why it worked. They also do not know if it will have the same effect in viruses.

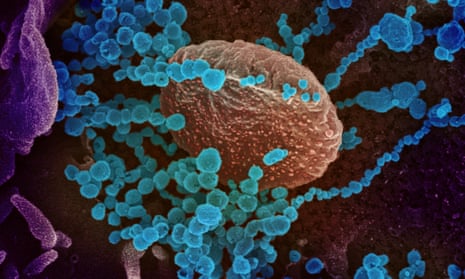

“The little bit we do know about the drug is it changes the way the cells make and distribute proteins, so we have speculated it might interfere with the ability of coronavirus to make its essential proteins,” he said. The trial is yet to receive ethics approval, but Hunt said the trial would be reviewed with urgency. Even fast-tracked, ethics approval can take six weeks and it would be up to six months before researchers had initial trial results, Pellegrini said.

The French, US, Indian and many other governments are rolling out trials for hydroxychloroquine in combatting Covid-19. The World Health Organization announced a large global trial, called SOLIDARITY, to find out whether existing drugs, including hydroxychloroquine, can treat or prevent the virus.

There are many benefits to looking at existing drugs to treat Covid-19, as they have already been tested and approved for use in humans, side effects are already known, and that means clinical trials can be conducted more quickly.

But there are good reasons media do not normally report on these clinical trials until they are complete and have undergone peer-review. Last week US president Donald Trump touted hydroxychloroquine as possibly “one of the biggest game changers in the history of medicine”. He also said that “it’s not going to kill anybody”, and incorrectly announced the drug’s approval had been fast-tracked. Soon after a US man died after he began drinking chloroquine because he was scared of getting sick.

The US drugs regulator also warned the drug could do more harm than good. There is months, if not years, of research that needs to be done to prove that something that kills the virus in a test tube will be both safe and effective in Covid-19 patients. There is a real risk of building false hope in a drug that has not been well-tested for this particular disease. Evidence from trials to date has been inconclusive and other evidence has been purely anecdotal.

Dr Gaetan Burgio, from the John Curtin School of Medical research at the Australian National University, said “recent results from clinical trials indicated a possible improvement in shortening the duration of the infection”.

“However the results are disputed and the clinical trials are inconclusive,” he said. “To date there are no clear indications that chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine are a treatment option. Additional clinical trials will tell us whether hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine are viable options for Covid-19 treatments.”

Covid-19 is an exceptional case because it is novel, is rapidly spreading, and countries are uniting to combat it, expediting ethics approvals for trials. Politicians are talking about these potential treatments almost daily, leading to media reporting on them, and the public, fearful of deaths, are hopeful for a cure.

Prof Peter Collignon, an infectious diseases physician who has worked as an advisor to the World Health Organization, said there were no quick fixes. “If I got Covid-19 tomorrow, I wouldn’t want any of those drugs being tested [on me],” he said.

“It could help with treatment, it could do nothing, or it could be very harmful, and at at the moment we don’t know which of those statements are true,” he said.

“Hydroxychloroquine is quite a worry for two reasons, including that people are already using it when there are marginal benefits for it, and people can take too high a dose and experience toxicity. So often, clinical trials give preliminary results that look promising but in doing the proper larger studies you realise not only that it doesn’t work, but it does more harm than good.”