If voters in my town are any guide to future elections, Australia will keep turning over political parties until its people find a team that gets it right, and that is because something is fundamentally broken in the relationship between government and citizens.

I mean people who are not involved in politics, the public service or any associated industries; not card-carrying party members or even political tragics. I mean casual observers rather than active participants.

“The major parties, the people who are running the country and keeping things going, they have lost contact with the local people,” a 60-something man tells me. When I ask him if he thinks it will change, he says, “When my grandkids are walking around with a walking stick.”

A third of the population, or thereabouts, now votes for minor parties. Nowhere is the diminished trust in the major parties more clear than in the Senate. After the 2016 election, the Coalition went into office with 30 senators. Labor had 26, and the crossbench – if you count the Greens, as the parliamentary library does – had 20 senators.

And if there was one thing that united those 20 senators on that crossbench, it was that they appealed to the voter using the old Democrats’ concept of keeping the bastards honest. If these senators could not get their hands on government itself, they could act as a check against major party power. The crossbench agrees that voters have lost faith in governments. The crossbench mostly agree on policies such as the financial services royal commission. (Labor came to this policy much later than the Greens and other crossbenchers.) The crossbench mostly agrees on the need for a federal anti-corruption body. Labor came to this policy in January 2018, at which point Malcolm Turnbull made comforting noises.

More than anything, the ideas that unite the crossbench represent my main street.

Conversations centre on lack of trust and the sense that clever political advocates have changed the system to suit themselves. Here is Ken, the former abattoir worker and history buff: “The major parties are there to see how they are going to fight to win the next election. It’s like a business. They are trying to outdo the other one. They aren’t worrying about the people out in Australia, they are just looking after themselves in one little corner. Bugger the ones outside.”

The separation is not just considered metaphorical. It is considered physical, like another country. There is Australia. Then there is the land of Parliamentalia – a castle surrounded by a moat. In Parliamentalia, anybody can argue any stance and make it sound credible. These skills, learned in school debating teams and university competitions on the road to a political career, have become the very things voters despise. Ipso facto, they don’t trust anyone who sounds polished. No one in their world speaks like a politician, which explains the attraction of the anti-politician politician.

The divide between the composition of the parliament and the people it serves continues to widen. The 2016 parliamentary handbook lists 226 members and senators, of which 91 describe their occupations as having been political consultants/ advisors, state and local politicians, party and union administrators, union officials, researchers and electorate officers, and public service/policy managers. Another 50 were in business as executives, managers or full-time company directors. Another 24 were lawyers and six were from the media. Of the recognisable jobs outside the extended political system, there were eight farmers, five military or police officers, four doctors, one teacher, one in real estate and one a psychologist. Thirty-two per cent of the parliament is made up of women. This is our representative body.

Politics is driven by human nature. It makes sense that people with an interest in politics spend time in the offices of a politician. But when the parliament fails to reflect the people it serves, it is bound to increase the actual and perceived divide between served and serving. Then there is the nature of our meritocracy. Are these people preselected because they are the best candidates, or are they preselected because they know people in the game? As a result, are good people with more diverse life experiences being shut out? State and federal Liberal member Alby Schultz, our local MP for much of my early time in the country, told me once that his great advantage was he never wanted to be a minister, which allowed him a wonderful freedom to say what he thought. Ambition creates a ball and chain for the modern politician, and the main street recognises that.

Sitting in her drapery shop, surrounded by bolts of fabric, buttons and bows, Lorraine Brown explains how she feels that politicians have moved so far away from our main street. “Our politicians basically go from school to university, and do law and go into politics, and they don’t actually live in the real world and particularly at grassroots levels. I’ve said that to [a wealthy local businessman] over the years. He gets a bit carried away with grandiose things, and I say, “You have lived with money too long. You have forgotten what it’s like down here for us because you are not attached to it. So you forget how difficult it is down here trying to make ends meet.”

Taken for granted by the conservatives and ignored by Labor

Australia is different from the US in the way we perceive government. Voters here who are fed up with politics-as-usual still expect government to be active, though they often can’t articulate in what way; similarly minded American voters want government to get out of the way. In a small town, Australians have expected more from their governments because traditionally government has done more.

What people around me want are jobs so they can stay in their place; they want infrastructure; and they want the access to the health, education and broadband services that city people enjoy. But they want it without the crap that city people have to put up with. The congestion, the pollution, the pressure.

They expect the world to change but not too fast. Conversations about discontent with, and the failings of, government in country areas are invariably followed by “but I wouldn’t live in the city if you paid me”. People tend to be slightly more socially conservative (though not always) and economically interventionist. Their big beef is with the lack of trust they have in government and the lack of consideration of them from city-based power centres. They know their MP can’t fix every issue, but they want he or she to have a go. They don’t mind immigration as long as it’s done on the nation’s terms, not the immigrant’s terms. They feel if migrants want to come to Australia, they should be grateful.

These voters have many similarities with the swinging voters in the outer edges of the cities, but geography and culture differentiate them – those around me identify strongly as country people. These are obviously broad brushstrokes. I think of these country town people as the neglected class, sitting between those who rely more heavily on government payments, and landholders and businesses who have enough assets to cushion them from economic shocks.

The neglected class comprises the people who service the farms, look after the very young and the very old, keep the schools going, keep the hospitals running, do the council work (in the streets as opposed to sitting as councillors), stock the supermarket shelves. The neglected class are the very foundation of country towns, and you don’t hear about them from most rural MPs. The neglected class feel they have no sway over governments or politicians, and they feel inadequately represented by the media. They have no lobby group wholly representing them.

They can see an educated elite on both the left and the right looking after themselves and shouting at each other in a conversation that is largely held above their heads, away from their main streets. Their issues are often taken in vain by both sides if their concerns suit the agenda of the day, but if you consider the agenda of the major parties, the neglected class are mostly disregarded.

The resentment creeping back within this class towards the land-owning class approximates the local version of the insider–outsider dichotomy we have seen play out globally. The neglected class are breaking away from the majors because they feel taken for granted by the conservatives and ignored by Labor. The neglected class are happy to shake up the parliamentary house in a bid to be heard because a vote is their only chance. The hopeful vote.

They have voted Labor sporadically in the past, but as Labor has taken up socially progressive causes they have looked again towards the Coalition. There are resonances with Howard’s battlers on the urban fringes, but the neglected class strongly identify with their rural places and their rural culture. They are aspirational. The angriest of them want to be recognised, to be acknowledged in a world that is changing and moving past them.

In other words, the finest economic reform could put an extra $50 a week in their pockets but it would not change how they are feeling. The gentrification of some country towns has the capacity to make them angrier. Who can afford a $40 steak or a $25 brioche burger? Likewise, high commodity prices and inflating rural land prices will only stretch the gap between landholders and these voters. The neglected class feel as though they are losing ground and if you keep an eye on flatlining wage growth figures you might understand why.

In contrast, the landowning class that influences country areas often have connections to politicians, business and public servants. Perhaps people within this stratum have gone to school with people in power or, like me, they may have worked with them. They can find solutions to individual problems, or at the very least they know who in the system they can bother to get these problems addressed. The landowning class might be cosseted with tea and sympathy, but the neglected class have no such solutions or comforts. Their people are disconnected from power.

Voters are breaking from the mob to vote for outsiders

Major political parties have taught voters they cannot trust that governments will deliver on their promises or keep their prime minister in place, so voters are in the process of teaching political parties that they can’t trust their traditional allegiances. Politicians acknowledge this fact but don’t really know what to do about it. The unpredictability of voter behaviour has made it less likely that governments can achieve anything. Australian politics has become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Most politicians know that voters are breaking from the mob to vote for outsiders. Most politicians know that people are unhappy with the volatility.

The anger, meantime, continues towards all levels of governments – federal, state, local – because Government with a capital G is seen as the problem. The neglected class feel like they are doing their job, but politicians, governments and media are not doing theirs. It might not be a fully formed coherent argument. Who has time or inclination for that? It is the vibe, as they say in The Castle. When the New South Wales premier swanned into Young for the byelection, I asked 50-something tradie Tim if he went to see her. Nah, he says, I only would have gone if I could have 15 minutes with Gladys. What would you say? “What the fuck are you doing? You have got no idea. You don’t have a clue, you are just fucking the place up. I just would have to say that.” How are they fucking it up? “They are just liars. I would cut their wage in half, get rid of half of them. Just don’t be a liar.” What do they lie about? “Everything. You know that. You write about the bastards.”

Most of my fellow residents think I have an unhealthy and ultimately unfruitful job. “How do you do it?” is their most common question. Whether this vein of discontent ends in tears for the major parties in Australia is the great unknown.

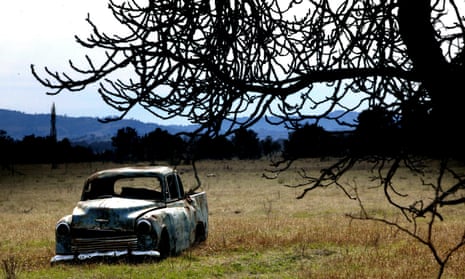

When I think about what might happen in rural politics in future, I look to the metropolitan electorates that hold the city version of the neglected class. No MP can get too complacent in the outer edges of our big cities. Those voters make their politicians work. Rural and regional main streets are starting to understand that. Like a bull led by a nose ring, rural electorates have more power than they think. That ring is an illusion. The bull still holds the power if he chooses to exercise it. Country towns are in a time of political transition and no one knows which way the bull will jump. Country voters are one fright away from determining governments. Rusted on electorates are rusting off.

Gabrielle Chan lives in the small town of Harden Murrumburrah, southern NSW. She will appear in conversation at Gleebooks, Sydney, 6 September, 6pm

This is an edited extract from Rusted Off – why country Australia is fed up, by Gabrielle Chan (Penguin Random House, $34.99)

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion