I know the spirits are out here. And when the wind starts to howl across the plain in great booming gusts, it might just be the sound of them crying.

I’ve visited many massacre sites in Australia. But usually I’ve been in the company of a local Indigenous custodian, someone who rubbed their scent on my face and hands and chanted to warn the spirits that this white man comes in peace. While it feels like I’m anything but alone, I’m by myself in the long grass that is blowing sideways.

All around, the fields shimmer in kaleidoscopic gold, russet, black and India green as the sun strobes through the storm clouds scudding across the sky. The rain arrives horizontally in icy needles, stinging my bare legs and arms as I plod around looking for the creek I’m assured is here somewhere. I’m vigilant for the prolific black snakes. It’s a spring Saturday in Queensland.

Names are important

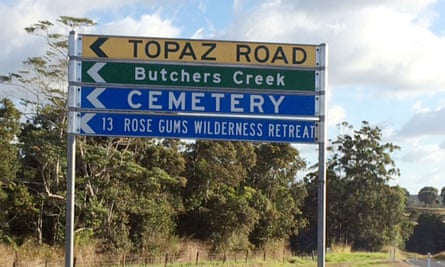

In contemplating the creek, I’d had in my mind a treacherous torrent running through a great black ravine, so imbued is this place with malevolence, right down to its name, Butchers Creek. But it’s scarcely a creek at all – more a gentle furrow padded with grass and lichen through which a stream trickles.

A little ramshackle goldmining town once sprang up near the creek but it has long ago ceased to be. The town was named Boonjie, an Indigenous word, after the creek whose banks had been a meeting place for countless thousands of years for a tribe of the Ngadjon rainforest people. The Ngadjon were a physically diminutive mob, perhaps because they thrived mainly on native plants and nuts in a place where protein, mostly tree kangaroo, was tough to bag. Thanks to the rainforest canopy that sheltered them they were also lighter skinned than the tribal people of the coastal plains and continental centre.

In 1887 white miners and “black police” (Indigenous recruits from elsewhere who had little compunction about killing other Aboriginal people at the behest of white so-called settlers) massacred a big group of Ngadjon camped near Boonjie. This was a reprisal for the murder of a Swedish goldminer, Frank Paaske.

Among the tablelands mining and pastoral community there was much pioneer boasting (some of it apocryphal) about the massacre. One settler, Fred Brown, detailed a “dispersal”, including the stake-out of the Aboriginal camp overnight. He told of shooting a man with his “old Schneider rifle” (“makes a bigger hole leaving the body than on entering it”) and of “protecting” a Ngadjon boy who survived. By some accounts the child’s name was Poppin Jerri. The child was apparently snatched from the hands of a black tracker about to dash the child’s brains out against a tree. A few days later the little boy was given to a Scottish-born zoologist, Robert Grant, and his wife, Elizabeth. Grant worked for the Australian Museum in Sydney. The Grants took the boy home with them and raised him – apparently on equal terms with Henry, their natural child.

This hints at a story that Australian history has scarcely addressed: the widespread theft of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families on the colonial and post-federation frontier. (Shirleene Robinson’s book Something Like Slavery? tells some of the story and is an invaluable exception.)

Many black children were stolen before the forced removal of Aboriginal children became a mainstay of assimilationist policy in the 20th century. At least one Indigenous man – an elder known to his people as Narcha but named by the miners as Barry Clarke because he had worked for a successful miner and pioneer, George Clarke – was also spared. Narcha had five wives and many children. Still, the child went to the Grants, who had been working in the area on a field trip, because Elizabeth had apparently wished “to get a little black boy”. The “little black boy” was renamed Douglas Grant and sent to school in Sydney.

Meanwhile, the killers replaced the name Boonjie with Butchers Creek. Today the name Butchers Creek applies to the creek itself and to the small, largely non-Indigenous community around it, with its modest hall and school. The renaming of Boonjie is disquieting enough. But dozens, perhaps hundreds, of places across the continent have been named or renamed, not to conceal but to commemorate terrible acts of violence against Indigenous people.

There is a Skull Creek in each of Gippsland, the Northern Territory, Western Australia and Queensland. There’s a Massacre Bay in Victoria, a Massacre Waterfall in Borroloola, a Slaughterhouse Creek in New South Wales and another Butchers Creek in Victoria. There were massacres in each of them. Twelve places in Queensland (where colonial and post-federation violence against Indigenous people was most pronounced) are named Skeleton Creek but official records fail to reveal how many of these names commemorate massacres.

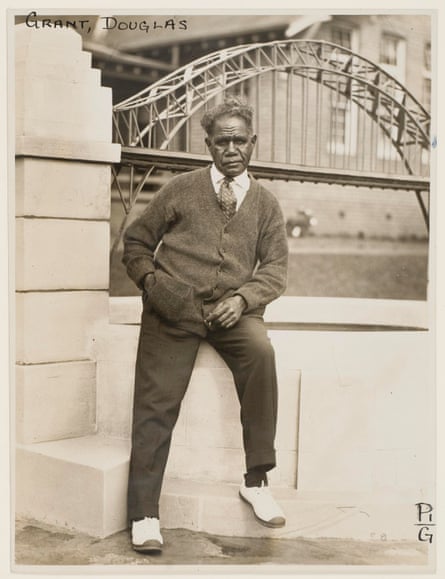

But back to that little watercourse on the Atherton tablelands, where in 1887 the boy survived to become Douglas Grant and his people’s creek was renamed not to commemorate those murdered but the very act of murdering them. Douglas Grant’s life draws together the competing historical elements of the Australian national narrative. As an Indigenous person, he was removed from his family with extreme violence, served in the 1st Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and became a prisoner of war in Berlin. He was later an Aboriginal rights activist and semi-vagrant in Sydney and Melbourne.

Through him or, at least, through the boy Poppin Jerri – we have a way in to the story of the first big conflicts, the Frontier Wars, that raged across this continent after the initial east coast European contact in 1770 and the invasion in 1788. For what happened to Poppin Jerri’s people at Butchers Creek was replicated in an unknown number of battles, skirmishes, guerrilla attacks and reprisals as the pastoral and mining frontier crept further north and west. These conflicts killed countless – because uncounted – Indigenous people. The deaths of police, soldiers, settlers, shepherds and convict labourers are more quantifiable; they were quantified because those doing the counting thought these deaths mattered.

Counting the uncountable

It is conservatively estimated that there were 20,000 violent deaths of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people nationally from 1788 until Coniston in the Northern Territory in 1928. This figure is used consistently by historians such as Henry Reynolds and John Connor, who have been at the vanguard of promoting cultural awareness about frontier war since the 1980s. Sceptical historians have contested this figure, though not that of 2,000 non-Indigenous combatants and bystanders (a ratio of some 10 to one).

More recent academic research indicates, however, that the fatalities figure might have been at least three times higher than 20,000. Indeed, the evidence suggests the true black–white ratio of frontier war deaths in Australia might have been 44 to one. Historians Raymond Evans and Robert Ørsted-Jensen have concluded that in Queensland alone at least 65,180 Indigenous people were killed from the 1820s to the early 1900s. Considering Evans and Ørsted-Jensen focus just on Queensland, their findings have implications for the number of Indigenous Australians killed continent-wide.

If Evans and Ørsted-Jensen are to be taken seriously (and on the basis of their research, first made public at the 2014 Australian Historical Association conference, they ought to be) that is another reason why Australia should engage in a mature discussion about the conflicts that raged across the frontier and perhaps cost some 65,000 lives in Queensland alone – more than the 61,000 Australian deaths in World War I, the conflict that has so embedded itself in Australian consciousness. If settler Australia is ever to deal properly with frontier conflict and its continuing legacy, that body-count comparison would be a good place to start.

Evans and Ørsted-Jensen scoured the remaining records of the Queensland Native Police Force and studied the prevalence of “black police” barracks from 1859 to 1898 to determine the approximate number of patrols, contacts and killings, based on reported body counts:

[W]e arrive at the sobering total of 41,040 Aborigines killed during 3,420 official frontier dispersals across almost 40 years of conflict. This mortality figure … is a mathematical and statistical projection, produced by cautiously sampling the fragmentary evidence left to us about the severe degree of destruction accompanying the long project of land dispossession in colonial Queensland. It is not and can never be a precisely accurate figure, nor is it a confidently absolute or maximal one. That number will never be known … Furthermore, let us be entirely clear about what we are claiming here. The 41,040 death rate does not represent anywhere near a full quotient of those who fell on the Queensland frontier. It is merely a native police statistic that does not even cover, at this point, official dispersal activities across the prior decade of 1849-59. These may well have accounted for another 3,000–4,000 deaths.

The 41,040 number also excludes actions against Indigenous people carried out not by police but by settlers. The authors calculate that these incidents accounted for 43% of the total number of clashes or approximately 2,580 clashes, giving a total of 6,000 clashes, police and settler. Evans and Ørsted-Jensen conclude that their body counts for native police and settlers “amount to no less than 61,680 in 6,000 attacks”. They add another estimated minimum of 3,500 Indigenous and 1,500 settler deaths for the 1850s to “arrive at an aggregate of 66,680 killed” between the 1820s and early 1900s.

Evans and Ørsted-Jensen’s research confronts the received view that the Australian wars that matter – or even the only ones that happened – are the ones that were fought overseas. The authors know their research makes some of us feel uncomfortable. Massacre denialism among some Australians and the mainstream media has driven the authors towards conservative calculations. Still, they want “to return to history the full ledger of those who, long ago, died protecting their sovereignty, their cultures, their homelands and their peoples but whose deaths were more often hidden than acknowledged by a society that made furtiveness its watch-word”.

The Evans–Ørsted-Jensen research bears directly on the themes of this collection of essays. Of course war is important, as one of the many influences on making Australians what we are, but this is not war as most of us have known it in the last century. Because the research indicates a frontier conflict death rate in Queensland alone that eclipses Australian fatalities in World War I, the authors effectively argue that the Great War was never the greatest war in Australian history. They quote with approval Henry Reynolds, who says what happened on the domestic frontier “was clearly one of the few significant wars in Australian history and arguably the single most important one. For Indigenous Australia, it was their Great War”.

The silence

In his 1968 Boyer Lectures, anthropologist WEH Stanner called it the “great Australian silence”. He was referring to the failure of a number of books to substantively address Australian Indigenous history, including frontier violence:

It is a structural matter, a view from a window which has been carefully placed to exclude a whole quadrant of the landscape. What may well have begun as a simple forgetting of other possible views turned under habit and over time into something like a cult of forgetfulness practised on a national scale.

There has been lumbering progress since Stanner’s lectures almost half a century ago, not least among historians, even of the centre right. Writers of novels, narrative non-fiction, popular history, plays and screenplays have increasingly addressed the extreme violence meted out to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders on the colonial frontier and later, down to Coniston in 1928, which remained for some people until quite recently, a part of living memory.

Indigenous Australia’s enduring culture of oral history (often reflected in music, visual art and dance) records the violence of the frontier (and corroborates what happened) in no less detail than the written words of the white perpetrators. In One Blood: 200 Years of Aboriginal Encounter with Christianity, John Harris recounts the description by early anthropologist EM Curr of the colonial violence involving Indigenous people and invaders. Curr said it would usually take up to a decade after a settler’s occupation of land before traditional owners were let back in as visitors or to hunt nearby, during which time “the squatter’s party and the tribe live in a state of warfare”. Settlers would shoot “down a savage now and then when opportunity offers, and calling in the aid of black police from time to time to avenge in a wholesale way the killing or frightening of stock off the run by the tribe”. More cattle would be speared, more Indigenous men shot down. “In revenge”, Curr said, “a shepherd or stockman is speared”. The violence would escalate with the introduction of the “black police”, officially the native police, a tragic, little-explored phenomenon among white historians of frontier justice, whereby rival tribesmen would be enlisted and militarised to slaughter other blacks. Curr explained how these men would be “enlisted, mounted, armed, liberally supplied with ball cartridges and despatched to the spot under the sub-inspector of police”.

Hot for blood, the black troopers are laid on the trail of the tribe; then follow the careful tracking, the surprise, the shooting at a distance safe from spears, the deaths of many of the males, the capture of the women, who know that if they abstain from flight they will be spared; the gratified lust of the savage, and the sub-inspector’s report that the tribe has been “dispersed”, for such is the official term used to convey the occurrence of these proceedings.

When the tribe has gone through several repetitions of this experience and the chief part of its young men been butchered, the women, the remnant of the men and such children as the black troopers have not troubled themselves to shoot, are let in or allowed to come to the settler’s homestead and the war is at an end. Finally a shameful disease is introduced and finishes what the rifle began.

The stories about the massacring (and other terrible abuses) of Indigenous people are easy to find in the archives of major cultural institutions in Australia and Great Britain. The personal journals, diaries, letters, memoirs and, indeed, the published works of colonial and post-federation officials, troops, police, farmers, miners and pioneering frontiersmen (and women) are replete with accounts of battles with – and all too often reprisal massacres of – “natives” who are invariably referred to as “marauding”, “troublesome” or “threatening”. Through the National Library of Australia’s Trove, very old government records and digitised newspapers can easily be found. They recount in detail the violence described by Curr. Little probing is needed to uncover biographies of the white men – such as Mounted Constable George Murray, former Light Horseman and Gallipoli hero, overseer of the murder of 31 Aboriginal men, women and children at Coniston – responsible for the slaughter.

Sometimes the blacks were simply hunted for sport or for “trophying”. Little imagination is required to decipher this malignant euphemism. The body parts – especially skulls – of Indigenous people were highly sought after in early Australia. Indigenous body parts are still being surrendered to organisations, such as the repatriation unit of the National Museum of Australia, that are mandated to return them, where possible, to their country. In recent years the museum has housed body parts of as many as 600 individuals; other state museums have their own collections that cannot, for various reasons (including a lack of detail about precise provenance) be returned to country.

There is ample proof that some Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders were hunted and killed merely so that parts of their bodies could be kept as curios. Bodies left at massacre sites became part of the collections of museums, medical research institutions and universities. Meanwhile, the bodies of Indigenous people who died in institutions were, barely cold, stolen and sold or given to other institutions.

The head of Onyong, the Ngambri chief, was turned into a sugar bowl and kept for years at a Tuggeranong homestead near Canberra. Other bodies were ransacked from sacred burial sites by men like George Murray Black, a farmer from Gippsland, who supplied countless skeletons to the Australian Institute of Anatomy, the University of Melbourne Medical School and many institutions in Europe.

Early newspapers offer concurring accounts (chilling in their candour and boastful detail) of the organised killings of black men, women and children on the frontier. In the journals and diaries of the frontiersmen, meanwhile, what is disquieting is the detachment of the perpetrators, the purpose that bleeds into their words as they describe the killing, the sense that they are involved merely in the extermination of subhumans.

None more so than the memoir of Korah Halcombe Wills (1828–96), a former mayor of Bowen and Mackay in Queensland, who reminisced at the end of his life about dispersing Aboriginal people in the mid-1860s. His account makes difficult reading, as he boasts of massacring Aboriginal people and chopping a man into pieces to keep as trophies. (Wills was a butcher by trade and later a publican.) He found this work to be “a horrible repulsive thing” but he persisted because “I was not going to be done out of any pet specimens of humanity”. He stuffed the body parts into his saddlebags to take home.

Wills fancied a live trophy as well, so “from out of one of these mobs of blacks I selected a little girl with the intention of civilising, and one of my friends thought he would select a boy for the same purpose”. Wills recalled that:

My little protégée of a girl … rode on the front of my saddle [to Bowen] and crying nearly all the way … I took compassion on her and decided to take her home and bring her up with my own children, which I did, and even sent her to school with my own.

The child died. This saddened Wills, though not as much as the death of a favourite horse.

The archives contain a story, too, of children stolen at the sites of Indigenous mass murders, from Appin in 1816 – during this operation Governor Lachlan Macquarie ordered that his troops “select and secure” 18 children, aged between four and six, for his “native institution at Parramatta” – to Boonjie, soon to become Butchers Creek in 1887, and well beyond to the stolen generations of the 20th century.

Which brings us back to Poppin Jerri, the little boy who survived the Butchers Creek massacre to grow up as Douglas Grant, an Aboriginal man who spoke with a Scottish burr, thanks to his adoptive parents and his education at Sydney’s Scots College. Grant was conscious of his colour while growing up but, raised in a white adoptive family – although he never inherited and he ended up on the street – he lost all contact with his culture. Grant enlisted in the AIF in mid-1916, just as Australian casualties on the Western Front were mounting. He was among 400 to 1,000 Indigenous men accepted as volunteers, despite the regulations that recruits were to be of “substantially European descent”.

Belated recognition?

The Australian War Memorial embraces the war service of Indigenous Australians who bypassed the racist regulations and fought overseas for Australia. Men like Douglas Grant have been used to support a theme that, in the army, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men experienced equality for the first time, although they were not treated as equals in civilian Australia, where most could not vote, were paid less than non-Indigenous workers, had been evicted from traditional lands, and were not yet counted as citizens. After demobilisation, though, many of these men returned home to find that their children, along with their wages, had been taken by the so-called protectors. Settler blocks for white veterans – blocks denied to the “black diggers” – were sometimes carved out of ancestral lands. Many returned servicemen’s clubs would not admit black veterans, and some black returned men were also denied appropriate repatriation and medical support.

The War Memorial holds that Grant, whose life was partly the inspiration for the Wesley Enoch play Black Diggers, is an exemplar of such positive experience. But that is far from true. Grant was adopted into a white European-Australian family, raised with a commensurate sense of entitlement and accepted, due to his adoptive parentage, as a citizen. It was not until he attempted to enlist that racism stung him. He was initially rejected because of his colour.

In May 1917, when he was wounded at Bullecourt and captured, his colour once again determined his fate. He was imprisoned in Berlin with the black soldiers of the Empire – mostly men from Africa and the Indian subcontinent. The Germans, no less attracted than the British to the voodoo “science” of eugenics and phrenology (whereby a man’s intelligence and personality could supposedly be determined by his head shape) measured Grant’s skull and fashioned a replica in alabaster. Grant, whose broad nose, distinctive brow and shiny skin distinguished him from all other prisoners, was given the run of the city. It was assumed, correctly, that he would be too conspicuous to attempt escape. This must have had an upside for Grant, a cultured man who loved music, art (he won competitions in Australia and was a fine draftsman) and, most of all, museums.

After the war, Grant returned to Australia disenchanted. He was in and out of work, often homeless and battling with alcoholism. He advocated for the rights of “black diggers” and he became, especially after Coniston in 1928, a vociferous campaigner for Indigenous rights generally, highlighting the history of massacres across the country and urging greater protection for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. He died in 1951 at La Perouse, on the northern headland of Botany Bay, land continuously occupied by the Kameygal for tens of thousands of years.

Black diggers, the coloured warriors of the 1st AIF, make quite a story for the War Memorial. But the memorial, its council heavy with former military personnel and writers of traditional military history, refuses to countenance telling the story of the warriors who died at the hands of soldiers, settlers, militias and black police after invasion in 1788. The memorial has, I believe, occasionally used the black diggers narrative as a fig leaf to distract from its intransigence on the Frontier Wars.

Some years ago, when I put questions to the memorial on its refusal to commemorate frontier conflict, the response directed me to its detailed stories about Indigenous service personnel from all other Australian wars. The Australian defence force also uses the history of Indigenous service – in uniform – to attract new Indigenous recruits. Many people officially associated with the memorial deny that frontier conflict was “war”, even though numerous settlers, as well as British commanders like Governor Macquarie, called it such.

The Australian War Memorial Act 1980 clearly allows the memorial to tell the combat story of military forces of the crown raised in Australia before and after the establishment of the commonwealth, but it chooses not to do so. Opponents of frontier war “recognition” by the memorial – the current director, Brendan Nelson, included – argue that no Australian-raised army units waged war against black people. Prominent historians say this is wrong and point to, among other units, the Military Mounted Police, raised by the British army in Sydney in 1825, which participated in numerous attacks on Indigenous people, including at Slaughterhouse Creek in 1838.

And then, of course, there are the infamous black police – military units raised solely from men who were born and bred on this continent and whose antecedents can be traced back tens of thousands of years. They were the police involved in massacres like that in 1887 when Boonjie became Butchers Creek and Poppin Jerri became Douglas Grant.

Narcha to his Ngadjon people (Barry Clarke to the killers) lived on after the massacre until 1903, surviving, it is said, another mass murder at Butchers Creek. Upon his death, he was mummified in a traditional manner and remained, unburied, with his rainforest people. In 1904–05 a German-born Darwinian anthropologist, Hermann Klaatsch, travelled the Atherton Tablelands to “attack the problem of the origin of Australian blacks, and of their import in relation to the whole development of mankind”.

He stole Narcha and several other mummified adults and children. Klaatsch shipped Narcha to Berlin, where he was displayed prominently in a glass case at the Museum of Ethnology in the Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse. There is every chance that the distinctive captive Douglas Grant, once Poppin Jerri, free to roam Berlin, saw Narcha there behind glass, having been separated from him at a massacre at Butchers Creek 30 years earlier. If so, this reunion held a tragic poignancy. For Narcha, it is said, was in all likelihood Poppin Jerri’s father.

This essay is taken from The Honest History Book, edited by David Stephens and Alison Broinowski and published by NewSouth, priced $34.99