When Conservationists Kill Lots (and Lots) of Animals

Invasive species are sometimes trapped, poisoned, and shot in large numbers to save native species from extinction. Some scientists say the bloodshed isn’t worth it.

The desert of south-central Australia is crenellated with sandstone hills in shades of ivory, crimson, and apricot. The ground is littered with dead trees and tree limbs, big hunks of transparent mica, dried cow dung, and thousands of stone spearheads and blades made by the Aboriginal people who lived here for tens of thousands of years—and live here still. Around the few water holes are the doglike tracks of dingoes, wild canines that were brought to Australia thousands of years ago and are now the country’s top predators.

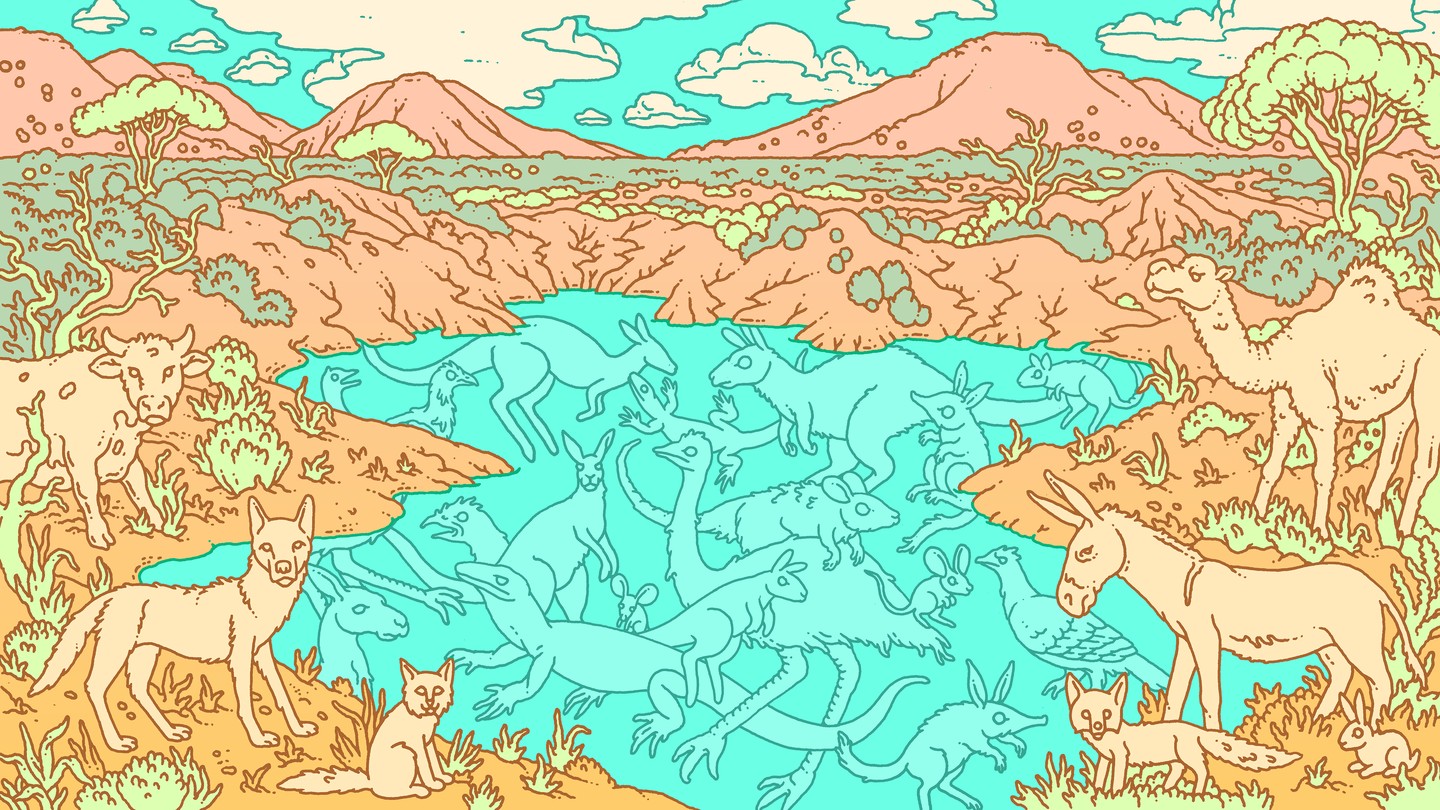

I have come to the Evelyn Downs ranch, on the famously remote highway between Adelaide and Alice Springs, to meet Arian Wallach, a conservationist who thinks there is too much killing in conservation. Wallach has come to this massive 888-square-mile ranch because it is one of the few places in Australia where people aren’t actively killing wild animals. Tough, outback Herefords share the landscape with kangaroos, wild horses, wild donkeys, camels, emus, cats, foxes, native rodents, dingoes, and very large antediluvian-looking reptiles called perenties. Of the animals on this list, dingoes, cats, foxes, horses, camels, and donkeys are all killed in large numbers throughout Australia—but not here. Wallach has convinced the owners to experiment with a more hands-off approach.

For a few days, I’m joining Wallach and her team as they kick off a season of fieldwork. Accompanying her are Adam O’Neill, her partner and scientific collaborator, and two of her students: Erick Lundgren, an American who is studying feral donkeys, and Eamonn Wooster, an Australian who has an image of his study species, a red fox, tattooed on his leg.

On our way into the ranch, we stop at a water hole to check its level. Across the sunken puddle, a buff-colored donkey with an elegant neck stripe trots down the slope to drink. Then a larger, darker donkey shows up and pulls rank, braying and snorting and claiming the right to drink for itself. The researchers watch, rapt.

Donkeys were imported into Australia in the late-19th and early-20th century from Spain, Mexico, India, Sumatra, and Mauritius as pack animals. Some escaped, some were lost, and some were simply released into the desert when they were replaced by machines. The latest government estimate, from 2011, puts the feral-donkey population of Australia at five million. From a traditional conservation perspective, they’re less than worthless because they are non-native and contribute to overgrazing. Agents employed by ranchers, national parks, and state governments frequently shoot them from helicopters.

Before leaving the United States for Australia, I read a report from the Australian Broadcasting Corporation that 6,000 wild buffalo, horses, donkeys, and pigs had been culled from Kakadu National Park in 24 days. I absorbed the information, but felt little. Sitting in the flies and the heat, watching the soft muzzle of a caramel-colored Nubian wild ass ripple the surface of the water, it occurred to me that I did not want this individual animal killed. But one donkey doesn’t change the environment. Ecologists contend that in their free-roaming tens of thousands, non-native herbivores graze the desert to dust and turn wetlands to mud barrens.

Wallach and her students say donkeys and other non-native species have been scapegoated. Lundgren says he has been unable to find any studies showing that donkeys destroy diverse ecosystems: “It seems very evident to me that the only herbivores to be substantially affecting plant communities there are the cattle—that are maintained at such ludicrously high densities.”

In cases like these, where most conservationists see killing non-native species as an obvious way to help restore a degraded landscape, Wallach sees a puzzle to be solved. Step one: Stop overstocking cattle. Step two: Stop killing dingoes that might prey on the donkeys and keep their numbers down. Do this and the ecosystem will sort itself out—no killing required.

Wallach is one of the most prominent voices in an emerging movement called “compassionate conservation,” which claims that all or nearly all conservation killing is unnecessary. It is still very much a minority position in a field that prizes biodiversity and nativeness and sees extinction as the greatest evil.

Mostly, compassionate conservation concerns itself with identifying ways to save species without killing, and this seems like a straightforwardly good idea. Why cause pain and suffering if there is another way? But I am interested in the hard cases where there is no other way, where conservationists really do have to choose between killing off thousands of animals and letting a native species go extinct. Then what do they do?

After our moment with the donkeys, it is time to set up camp. Wallach directs operations. She makes a lot of very direct eye contact, her green eyes blazing with intensity under the keffiyeh she wears in the field to keep off the salt-hungry flies that swarm around us during the day. If you are doing something wrong, she’ll let you know, then teach you how to do it the right way. She eats the exact same thing for breakfast every day in camp: veggie sausages, sautéed peppers, and a potato pancake, which O’Neill cooks for her.

O’Neill is 16 years older than Wallach, and speaks with a broad Australian drawl that contrasts with her carefully enunciated international English. He looks genuinely weather-beaten in a way she does not. He hunts kangaroos for his own consumption—a more ethical source of meat, in his opinion, than industrially-raised cows or pigs—and smokes an endless string of hand-rolled cigarettes, both habits that Wallach disapproves of but tolerates. At their home in rural Queensland, the couple share their lives with two rescue dogs and a large flock of free-range laying chickens.

After making camp, the team begins setting up camera traps to record the behavior of dingoes, cattle, cats, foxes, donkeys, and camels around water holes. We spend a day setting out dozens of trays of peanut pieces, covering each tray with a layer of sand. Once the local rodents discover the trays and get used to raiding the peanuts, some trays will be spiked with the scat of various animals to test whether native rodents are afraid of cats, foxes, and dingoes. The idea is that if the smell of the scat makes the rodents anxious, they’ll spend less time at the tray, which can be measured by how many peanuts they eat before they scamper off.

With this project and others, Wallach and her team are probing how native and non-native animals interact, gathering data to make the case that they can and should coexist. Wallach believes that many native species can learn to live with non-native cats and foxes, but this is, again, a minority position.

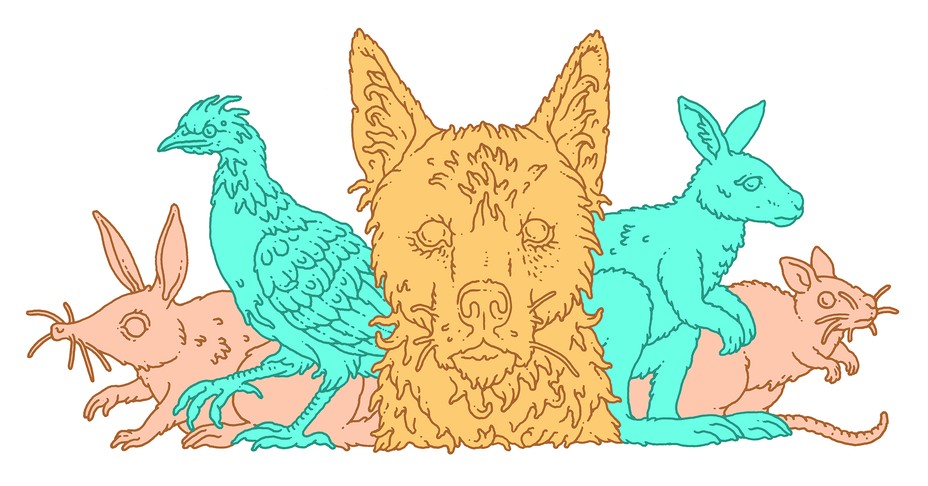

Like donkeys, horses, and camels, cats and foxes were introduced to Australia by settlers. These feral predators seem to eat just about anything bigger than three-quarters of a pound and smaller than 12 pounds—what Australian ecologists call the “critical weight range.” Inside this range is a menagerie of animals with wonderful names and uncertain prospects, among them the elegant predatory marsupial known as the spotted quoll; the bilby, which looks like a lean, erudite cousin of the rabbit; the chicken-like malleefowl; and the mini-wallaby known as the woylie. Every night, foxes and cats kill millions of native animals and together they have helped drive more than 20 species extinct, including the unsurpassably adorable big-eared hopping mouse. Thus governments, conservationists, and some landowners in Australia not only shoot large herbivores but also shoot, trap, and poison cats and foxes.

It is impossible to get accurate data on how many animals are killed in Australia. The federal government doesn’t collect statistics on animals killed by their own departments, and the various state and territory governments don’t collect data either. A spokesperson for the Queensland state government gave me a typical response: “Feral-animal control is scattered across so many agencies [that] it would be very difficult to quantify with any accuracy.” One academic effort to get a handle on the scale of control determined that few records are kept, and that “institutional memory about pest control activities declined sharply after 5 years and was almost non-existent after c. 10 years.” Animals, in other words, are simply killed and forgotten.

The state of Victoria did provide me with one arresting statistic: Each year on average, they pay landowners and hunters almost a million dollars in bounties for fox scalps—at $10 per scalp.

In 2015, the Australian government pledged to kill 2 million feral cats by 2020. During the first year of the push, they killed 211,000 cats, and they are currently collecting data on years two and three of what Threatened Species Commissioner Sally Box describes as “humane, effective and justifiable feral-cat management to protect our unique wildlife.”

Just this year, the Australian Wildlife Conservancy began clearing 9,390 hectares of foxes and cats for what will be the largest “feral predator-free” area on the Australian mainland, the Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary in Central Australia. Cats and foxes are typically killed with cage traps—in which the animals wait for hours until death arrives on two legs—or with 1080 poison, which causes vomiting; auditory hallucinations; irregular heartbeat; rapid, uncontrolled eye movements; convulsions; and liver and kidney damage.

Australians also kill a lot of dingoes, mostly to protect sheep. Ten miles north of the town of Coober Pedy, near (in Australian terms) Wallach’s field site, I visit the dog fence, a truly epic testament to how much Australians can hate the dingo. Australian ranchers started building fences to exclude dingoes and rabbits in the 1860s, and in the 1940s those fences began to be joined up into a single, 3,500-mile-long wire fence designed to protect sheep in the country’s southeast. When I drive out with a local tour guide to see the nearest stretch of fence, I am unimpressed. Strung through twisty posts made of the local mulga tree, it is a rickety-looking five-or-so feet of chicken wire that any decently sized mutt could easily dig under or vault over. But my guide explains that the fence itself isn’t really meant to stop dingoes; it is more valuable as a landmark for the pilots who drop thousands of baits, laced with 1080, in a swath of poison up to four kilometers wide.

The real purpose of these fence posts, it seems, is to hold up signs that say WARNING: POISON LAID. GREAT DANGER TO DOGS. RESTRAIN OR MUZZLE AT ALL TIMES. 1080 MEAT BAITS PRESENT AT ALL TIMES TO CONTROL WILD DOGS & OR FOXES ON THIS PROPERTY.

Australia may kill more animals than many countries, but as Wallach is well aware, this kind of bloodletting isn’t unique. Around the world, people routinely kill free-ranging animals to protect human interests. And there’s a surprising amount of killing in the name of conservation. To save rare plants and giant tortoises from extinction in the 1990s and early 2000s, conservationists shot roughly 140,000 goats on the Galapagos Islands, mostly from helicopters. To save rare birds on South Georgia Island in the South Atlantic, conservationists dropped 300 metric tons of poison bait on the island to exterminate rats between 2010 and 2015. In the United States, barred owls moving west of their own accord are shot because they compete for nesting sites for the endangered spotted owl. Sea lions that eat endangered salmon on the West Coast are trapped and given lethal injections. And in New Zealand, government officials have pledged to kill all of the rats, stoats, and brushtail possums in the entire country by 2050.

Wallach was born in Haifa in 1977 and grew up in Jerusalem, New York, and Switzerland. After earning an undergraduate biology degree in Israel, where conservation focused mostly on preserving habitats for wildlife in a crowded country, Wallach chose to go to graduate school in Australia, a country she saw as wild and wide-open. In the mid-2000s, she began graduate research at Arid Recovery, a fenced reserve in South Australia where all cats, foxes, and rabbits are killed to give the native animals a chance. “It was the first time I encountered what I now call the dark side of conservation,” Wallach says. “I thought conservation was a pure good.”

Wallach was shocked and confused by the amount of killing that went on in conservation, but found herself drawn to a man responsible for untold thousands of animal deaths: Adam O’Neill, who at the time was killing rabbits at Arid Recovery. A commercial hunter and professional “conservation eradicator” with little formal education, he once invented and built a cat trap that used a trip wire to trigger a 12-gauge shotgun. But many years in the field had led him to a theory that so possessed him that he wrote a book about it in 2002. If humans simply stopped killing dingoes, he proposed, Australia’s top predator could keep cat and fox numbers down all by itself, allowing native animals to thrive and humans to retire from shedding so much blood. By the time he met Wallach, he was seriously questioning the evidence behind the projects he worked on, and was almost ready to retire as a gun for hire.

Wallach and O’Neill soon started discussing ecological theory. And they started dating, making a perhaps-incongruous but compelling pair—a highly educated, cultured Israeli and a country boy with excellent aim. Katherine Moseby, the lead scientist at the Arid Recovery Reserve, remembers visiting the couple at their shared research campsite in the remote bush. “We are sitting there after dinner just looking up at the stars. It was a beautiful night. And Arian said, ‘And now I will play the harp.’ And she went to her four-wheel drive and pulled out this harp—like this full-sized harp. And she sat down next to the fire and she played her harp.”

The phrase “compassionate conservation” dates back to a 2010 symposium in Oxford, England, hosted by the Born Free Foundation, a charity that advocates for the welfare of wild animals. In the last eight years, its advocates have held a few conferences, published a number of major publications in conservation journals, and, in 2013, founded the Centre for Compassionate Conservation at the University of Technology at Sydney, where Wallach works.

The core mission of compassionate conservationists is to find win-win approaches where species are saved but no blood is shed. Where elephants in Kenya are being killed because they destroy farmers’ fields, the compassionate conservationist promotes a fence that incorporates beehives, since elephants hate bees. (As a bonus, the farmers can collect honey.) Where foxes are being killed on a small Australian island because they are eating rare little penguins, the compassionate conservationist installs guard dogs to look after the penguins and scare away the foxes. Often, advocates say, a solution can be found by examining what all the species in the area want, what they are thinking, and how best to tweak their behavior.

“It is actually a profound thing to realize that ecology is a bunch of sentient beings interacting in a landscape,” says Wooster. “They are not just eating and fucking machines.”

In one of their first scientific collaborations, Wallach and O’Neill compared populations of species in different arid areas in Australia. On the allegedly dingo-free side of the dog fence, they found that every population of yellow-footed rock-wallabies and malleefowl was living alongside dingoes. Stable dingo families—families whose breeding pairs weren’t repeatedly disrupted by killing—seemed to be the best at suppressing cats and foxes. In 2010, a study with two colleagues found a similar pattern at more sites and with more native animals. Not everyone is convinced, but the results suggest that in some contexts, dingoes can protect some native species.

But it is by and large illegal to move dingoes to the notionally dingo-free side of the dog fence, and socially difficult to convince anyone to stop killing them anywhere. So conservationists have continued to focus on creating fenced reserves free of all predators. The reserves produce generation after generation of bilbies, bettongs, wallabies, and other adorable creatures that are unprepared for life on the outside. When their populations grow too large for their fenced areas, they are sometimes “reintroduced into the wild,” where they are promptly eliminated by cats and foxes.

If these reserve-raised creatures could be released into an area whose predators were regulated by stable dingo families, Wallach and O’Neill think they would be able to hang on long enough to adapt to the new ecology of Australia—to wise up and learn how to raise families out in the big bad world.

Other ecologists say that this optimism simply isn’t supported by data. Moseby agrees that killing dingoes has “made it easier for cats and foxes to wreak havoc,” but adds that even a single cat can take out a hair-raising number of native animals, so suppressing their numbers may not be enough. “I just don’t think that it is as simple as adding dingoes and everything will be fine.”

Wallach agrees that more research would help clarify the strength of the dingo effect. But despite the continent’s wide-open landscapes, she says, it is nearly impossible to find a large area where dingoes have been left alone for long enough to settle down into a stable, calm social-ecological relationship with cats and foxes. This is why she wants to found a Compassionate Conservation Research Station, a piece of land at least as big as Evelyn Downs, where the new ecology of Australia could be observed with minimal human intervention—and definitely no killing.

After a day of setting up experiments, we are sitting around the campfire, warming ourselves on a very cold desert night as the Milky Way garlands the vast dark above our heads. I challenge Wallach with the problem of Gough Island, a tiny speck in the South Atlantic which is home to almost the entire breeding population of the critically endangered, and breathtakingly beautiful, Tristan albatross. The numbers of this huge white bird are declining at 3 percent per year, in large part because their chicks are eaten alive by descendants of house mice that came to the island with people before 1888. Population modeling suggests that unless something is done about the mice, the Tristan albatross will likely go extinct within a century. Was Wallach really willing to sit back and do nothing, to see that entire species snuffed out so she would not have to kill any mice?

Wallach says she finds my Gough Island question simplistic. First, these kinds of cases are uncommon, she says. Most species are declining for multiple reasons—including habitat loss and human actions—not just because of a single animal predator. And ultimately, what gives us the right to be the gods of Gough Island, to say who lives and who dies? The mice “aren’t our children that we can control,” Wallach says. “They aren’t our pets or our livestock. They have their own agency. Conservation is ultimately a chauvinist method that treats animals as automatons.”

So the Tristan albatross should be allowed to go extinct to preserve the agency of the birds and the mice? I find this hard to take. Wallach sighs. She’s seen the kind of death that poisons can deal out. Her own dog, Kuda, accidentally ate some 1080 bait and died screaming in her arms. The poison that would probably be used on Gough Island works differently, but it certainly isn’t pain-free. She says Kuda’s death was “by far the worst thing that ever happened to me in my life.” And she just can’t imagine dealing out that kind of death to any creature. “I would never do that to a mouse. I don’t care whose blood they are sucking on.”

I am reminded of a line from a recent Conservation Biology paper written by Wallach and four co-authors: “Where conservationists fail to find approaches that ensure both individual well-being and collective protection, a mark of compassion will be to endure the harrowing sense of immense responsibility and utter powerlessness that inevitably accompanies difficult decisions with no unequivocal answers.”

That line was written by Oregon State University graduate student Chelsea Batavia, who says she doesn’t know whether she would poison the mice on Gough Island, but says that either way, part of behaving ethically means sitting with the fact that neither option is good. If you do decide to kill, you should feel something besides self-righteous confidence. “The point is to pull the trigger and mourn it as a tragedy and a loss,” she says. “We need to become more comfortable with moral discomfort.”

While Wallach is unwilling to pull the trigger at all, Moseby feels that it is a moral obligation. “I don’t like killing things, but when you have worked with threatened species and you’ve seen them be annihilated by cats and foxes, you can either sit back and watch or you can do something about it,” she says. “I have seen firsthand the way that one cat can destroy an entire population.”

Moseby does agree that conservation could improve its predator-killing practices. “Right now, we throw 1080 baits out [on the landscape]. We will get better at targeting cats and foxes and maybe particular individuals.” One idea she is pursuing is implanting little poison capsules under the skin of reintroduced native animals. That way, only the cats that specialize in eating those species would consume the poison and die. Cats that stick to rabbits would be left alone. Moseby is also working on breeding savvier lineages of native mammals that would be able to coexist with cats and foxes. She feels the crisis demands action and intervention, “not sitting back and saying, ‘Let’s let everything eat each other and see what is left.’”

That’s not how Wallach and O’Neill would phrase it, but it isn’t far from their vision of a future where dingoes, cats, foxes, and native species coexist, without human meddling, in a new, stable ecosystem alongside other introduced animals like camels and donkeys—a radically different definition of success than that of the conservation mainstream, which instead seeks to preserve native animals in their native ranges, sticking whenever possible to the way the world was before humans changed it.

In the ecosystem Wallach and O’Neill envision, cats and foxes would still be killed; they would just be killed by dingoes, not by us. This is fine with Wallach, because dingoes are not subject to human morality. Although the world is filled with suffering, it is ultimately only human-caused suffering that Wallach seeks to eliminate—though she does still feel empathy for animals that suffer at the claws and teeth of other animals. “It is the very fact that life is comprised of suffering that creates the necessity for compassion,” she says. But she believes that when mice eat albatross chicks or dingoes kill cats, that is essentially not human business.

James Russell, a University of Auckland ecologist and a proponent of Predator Free 2050, calls this “a very naive view of human responsibility.” He believes that we all have some obligation to undo mistakes made by our fellow humans in moving species around, and that there’s little moral difference between killing an animal and letting an introduced predator do the killing. “We have to accept that [humans have] a larger collective responsibility,” he says. Russell says he and his colleagues look forward to a day when genetic engineering, or another technological “game-changer,” would allow humans to avoid causing animal suffering while saving species. But, “until that time, we have to do something.”

On one of the first days of the field season, Wallach sets up an outdoor shower which pumps water heated over the fire up through a hose. A naked body dries almost instantly in this climate. Once clean and presentable, the team pays a social call on the ranch next door, owned by the Lennons, an Aboriginal-Irish family that doesn’t kill dingoes. They are “our companions,” according to Bill Lennon, who wears a neat white beard, a baseball cap, and a mesmerizing opal ring set with a stone found nearby. “That’s our spiritual side,” he says.

Some Aboriginal people count dingoes as relatives; others have made their living as “doggers,” killing the canines for a bounty. In religious stories of various peoples, dingoes found water and created humans. In the old days, some Aboriginal women would suckle dingo pups and raise them as hunting companions. These dingoes would become kin and receive names, but after a year or two, they would usually leave their human families and return to the wild to find mates. So although the animals and humans sometimes lived together, the dingoes were their own creatures, making their own decisions about their lives. This distinguishes them from goofy, brash domestic dogs, which need looking after, says Lennon.

“Dingoes are a quiet animal,” he says. “If you’ve got a dingo that has been with you for yonks, they’ll only make this noise if there is danger.” He produces a low, soft sound of canine concern deep in his throat. “To me, it is music to my ears.”

This article is part of our Life Up Close project, which is supported by the HHMI Department of Science Education.