A Time Machine in the Mojave Desert

A four-story structure designed to recharge cell structure is now a recording studio and tourist attraction.

The sign said, “Dedicated to Research in Life Extension.” George Van Tassel, an aviator and UFOlogist, put it outside a structure he described as “a time machine for basic research on rejuvenation, anti-gravity, and time travel” in the Mojave Desert in the early 1950s.

In fact, the story of George Van Tassel’s Integratron, as the machine is known, is so outlandish, so otherworldly, and so enchanting—encompassing UFOs, electromagnetism, Nikola Tesla, Howard Hughes, Moses, and an alleged German spy—that it’s little wonder the site continues to attract tourists, artists, reporters, drifters, and spiritual pilgrims more than 60 years after Van Tassel began to build what would become his life’s work.

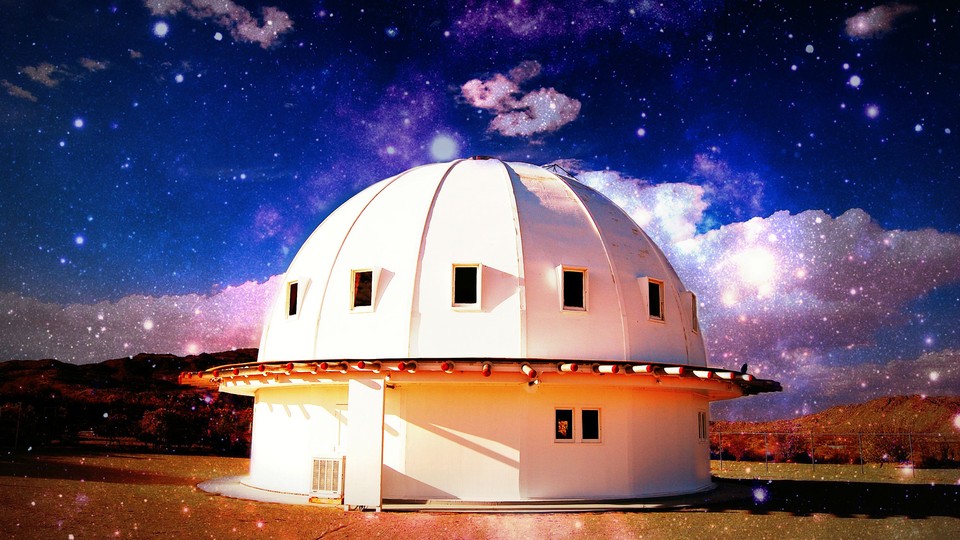

The white wood-domed structure sits four stories high and 55 feet in diameter, just off Twentynine Palms Highway in Landers, California, about an hour north of Palm Springs. According to Van Tassel, the site was determined by its relationship to the Great Pyramids in Giza as well as its proximity to magnetic vortices. It is a 16-sided metal-free building constructed using a technique called joinery—no nails or screws were used in an attempt to avoid interference with the conductive properties of the machine. Inside, the acoustically perfect sanctuary made of Douglas fir rises three stories high and features sweeping views of the desert from its 16 small windows. The Integratron remains open to visitors today, although it’s no longer outfitted for the purpose of time travel—the machinery is, mysteriously, long gone.

* * *

The story of Van Tassel’s time-travel dome begins under a rock—yes, an actual rock—where he lived. It was here, a few miles from Landers, that the inventor established an airport which he ran for 29 years on land leased from the U.S. government. It’s also where he incorporated a science philosophy organization called The Ministry of Universal Wisdom, one of many UFO cults that sprouted up in California shortly after the 1947 Roswell incident that brought UFO culture into the mainstream.

The most infamous of these groups is probably Heaven’s Gate—whose members committed suicide in order to ascend to a spaceship following the Hale-Bopp comet—but there’s also Scientology (founded in 1952), the Universal Articulate Interdimensional Understanding of Science (1954), and the Aetherius Society (1955). The organizations held in common the belief that communication with extraterrestrials was possible and that by channeling their messages (many aliens, believers said, were concerned with the earthlings' attempts to develop a hydrogen bomb) the contactee could ultimately help save mankind. “The UFO culture of the 1950s arose after the end of WWII, and rockets, nuclear weapons, and new aircraft were being designed and built based on war effort innovation,” notes Bernard Bates, a professor of astronomy at the University of Puget Sound. “People were afraid death could come out of the sky... and they were seeing all sorts of natural and human made phenomena which they didn’t understand.” It was during this era of increasing distrust among Americans of the U.S. government, the beginnings of the Cold War, with the possibility of nuclear weapons looming and the new-age movement in California blossoming, that Van Tassel rose to local, then national prominence as a charming, well-spoken UFO expert. Much of his notoriety was a result of the annual Giant Rock Interplanetary Spacecraft Convention, which he hosted for more than 20 years.

Seven stories high and many thousands of tons, Giant Rock dominates the desert landscape and became a local landmark due to its size. It was underneath the boulder that a German immigrant named Frank Critzer carved out a 400-square-foot house for himself where Van Tassel would visit him occasionally. The story goes that Critzer also installed a radio antennae on top of the rock and came under suspicion by the authorities for being a German spy shortly after WWII. Accounts vary, but a tear gas canister from a botched FBI raid is said to have somehow ignited Critzer’s store of dynamite and blown him to bits. Van Tassel moved in shortly thereafter with his wife. And on August 24, 1953, it was here that Van Tassel received his instructions regarding what would become his “tabernacle”—the Integratron.

Van Tassel liked to say that both he and Moses were compelled to build their tabernacles via instructions from a man that came out of the sky—in Moses’s case it was God, and in Van Tassel’s, an extraterrestrial. Van Tassel writes in his memoir I Rode a Flying Saucer that he awoke one night to find a man standing at the foot of his bed. “Beyond the man, about a hundred yards away, hovered a glittering, glowing spaceship, seemingly about eight feet off the ground.” The man introduced himself in English as Solganda from the planet Venus and invited Van Tassel aboard his ship, where he divulged the schematics of the Integratron. Its construction would become Van Tassel’s focus for the next 25 years.

Van Tassel’s interest in flying aircraft was borne out by his career choice. Born in 1910 in Ohio, he entered the aviation industry in 1927 after gaining his pilot’s license, and worked for both Howard Hughes at Hughes Aviation and Lockheed Aircraft during his career. Of Hughes he wrote, “One day with Howard was more to me than months I have spent with other men.” The author of four books, Van Tassel claimed to have made exactly 410 radio and TV appearances and gave hundreds of lectures across the U.S. and Canada in his lifetime—many concerning the mysterious dome he was building out in the desert. He was also quoted talking about his UFO visit in Life magazine in 1957—albeit mockingly.

The Life reporter, covering Van Tassel’s Interplanetary Spacecraft Convention for the magazine’s May 1957 issue, characterized the convention’s 1,200 “earthling” attendees—who came to swap stories of UFO abductions and hopefully spot a saucer or two after the sun went down. It probably didn’t help Van Tassel’s credibility that he announced at the convention that he’d decided to run for president in 1960 and that his extraterrestrial friends were going to help run his campaign. Even his supporters, like the fellow UFO enthusiast and author Trevor James Constable, acknowledged that Van Tassel was widely regarded by scientists as a crackpot. But despite the skepticism he faced from the media, Van Tassel’s devotees had no such hesitations—the Integratron was funded by donations from hundreds of supporters around the world. He calmly eschewed criticism of his theories and talked matter-of-factly about his communication with aliens and his belief in time travel. When asked by a skeptical interviewer if he was perhaps unbalanced or had experienced and “emotional upset,” Van Tassel replied wryly: “I’ve never had an emotional upset other than women.”

“Science continually disproves its own theories,” he explained about his willingness to believe. “This is the only gauge by which man can record progress. Even time is only recognized as it passes and events recorded after they happen. Man accepts three-dimensional theory, because the illusion is understandable to his limited thinking. With applied, undisturbed effort, man can develop his all-dimensional sense of being, and record time and events in the future, as well as present and past.”

But Van Tassel’s beliefs about the fluid and unreliable nature of time were in many ways a reflection on mortality. “The biggest trouble on this planet is, that when you get smart enough to do something with the knowledge you have acquired here, death intervenes,” he wrote. “Our life span is just too short.” Van Tassel’s solution to old age was “a high voltage electrostatic generator that would supply a broad range of frequencies to recharge cellular structure.” By recharging cells through electromagnetism, we could turn back the clock, thereby extending life span, he said. It wasn’t about transporting people through time—the aim of his time machine was to turn back the clock, to give our physical bodies more time. He compared it to charging a car battery—although as the professor Bates points out, the concept of charging cells is, like many of Van Tassel’s ideas, “too vague a concept to be considered a testable conjecture.”

Testable or not, Van Tassel directed his skeptics to consider the known-yet-invisible entities of gravity, oxygen, electricity, and magnetism, as well as the limits of our five senses which restrict us to a narrow experience of the known spectrums of light, sound, and smell. Humans have the capacity to see less than 1 percent of the electromagnetic spectrum, he noted in his writing, which means both birds and bees have the ability to see things we cannot. “Still, people go around saying, ‘I won’t believe something unless I see it,’” he wrote.

He was determined to provide his naysayers with irrefutable evidence in the form of his rejuvenation machine—which he believed would offer proof his alien encounter while benefiting mankind immeasurably.

The science behind the Integratron is based on electromagnetics. In his quarterly magazine Proceedings, Van Tassel described the ongoing construction of the building to his followers:

The armature, 55 feet in diameter, has been the most difficult part of this whole project. Requirements for anti-friction, expansion and contraction from heat and cold, and wet and dry conditions, have made this armature a mechanical wonder. Four times larger in diameter than the largest armature ever built, it floats on 16 Teflon-bearing blocks which are supplied with compressed air to "float" the armature on air. One-hundred and twenty pounds of air in each bearing block literally floats this 1,700 Pound spinner. The 64 Aluminum collectors are about to be mounted on the spinner.

The rotating armature was to be outfitted with 64 “static collectors” made of aluminum—capable of gathering 50,000 volts of static electricity from the air and delivering it to the cells of the participants inside. A large coiled copper wire running through the center of the building was also planned to aid conduction. Those undergoing the treatment were meant to receive this energy while stationed inside the machine, wearing all-white outfits. But while Van Tassel revealed much about his plans for the Integratron he also kept many of the details necessary for completing the project to himself. Van Tassel died of a heart attack in 1978—although apparently those who knew him to be in good health found his passing suspicious. His epitaph supposedly read: “Birth through Induction, Death by Short Circuit.”

Lacking funds, the necessary blueprints for completion, and their charismatic leader, the Integratron project soon stalled. The building was sold to a man who planned to turn it into a disco. It sat empty for years. Van Tassel’s equipment disappeared—making it difficult to determine just how much of his vision he had constructed before his death. It was bought by three sisters in 2000 who opened the building to the public and now promote it as a place of healing as well as advertising its unusual acoustic properties—the musicians Moby and Jason Mraz have both recorded there.

A healing sound bath session was fully booked on the day I visited. The group was a mix of young, curious East Coast tourists, and one gentleman from Los Angeles who confided this was his fourth visit—that after his first experience, he’d immediately booked again, and again. None of us was there hoping to become younger—we weren’t there for Van Tassel’s hopeful pseudo-scientific promises. But while the Integratron appears to have transcended its original purpose, now a standard stopover for visitors to Joshua Tree National Park and day trippers from Palm Springs, it still seems to provide something else intangible and appealing to its many modern-day pilgrims.

It’s a kind of cosmic or psychic architecture, mused Craig Hodgetts, a UCLA professor and partner of Hodgetts + Fung Design and Architecture, when asked about the continuing popularity of Van Tassel's dome. Along with pyramids, he noted that domes are purported to have “a kind of physical presence that’s supposed to be transformative towards the spiritual,” citing the Pantheon in Rome as well as the more modern geodesic domes of Buckminster Fuller. A dome is a platonic solid, it has centrality, it focuses on the center—it’s conceptually pure. So when we as travelers are drawn to the Integratron’s white dome rising out of the desert, or converge around I.M. Pei’s glass pyramid in the courtyard of the Louvre, Hodgetts suggests that kind of psychic architecture could be filling a basic, unmet need we all have relative to our more mundane environments—a kind of, “look over there, it’s something pure,” he suggests. “You have to take that dome as an article of faith that it works,” he said of the Integratron. “So it reaches all the way back into prehistory with a need we all have for a reflection of some universal principles. It’s a primitive thing.”

The current owners declined to be interviewed, saying, “we prefer that people glean their own experience directly.” And while the Integratron in its current state is far from what Van Tassel had envisioned, listening to a woman play a series of quartz bowls as part of a healing sound bath—in an “acoustically perfect” building designed for time travel and communication with extraterrestrials—still feels otherworldly.