James Watt was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist most famous for his work on the world’s first modern steam engine. He would modify the Newcomen steam engine to improve its efficiency through his creative thinking and scientific knowledge of instrument design. James’s work on the steam engine would prove to be a substantial contribution to the world and one that would, in no small part, help power the Industrial Revolution at home in Great Britain and in the rest of the world.

James Watt: A biography of the father of the modern steam engine

James Watt was one of the most important engineers and scientists in history. His work on the modern steam engine kick-started the entire Industrial Revolution.

James Watt

James would initially take up work building instruments at the University of Glasgow. Whilst there he would become interested in steam engines. He would quickly realize that existing steam engines wasted energy by repeatedly cooling and reheating the cylinder. To solve this he introduced a simple but significant improvement on the design. A separate condenser. This avoided the need to waste energy and radically improved the power, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness of steam engines.

James Watt would incrementally improve the engine’s design over the years. He added rotary motion and broadened the engine’s applications to uses beyond just pumping water. Watt would attempt to commercialize his invention but experienced many financial setbacks. That was until he entered into a partnership with Matthew Boulton in 1775. The pair would form a new company, Boulton, and Watt, which would eventually become very successful. Watt would eventually become a very wealthy man.

During his retirement, Watt would continue to tinker away. He developed several new inventions but none of them were as significant as the steam engine. He would later die at the ripe old age of 83.

Early years

James Watt was born on January 19th, 1736 in Greenock, Renfrewshire, Scotland. His father was the treasurer and magistrate of Greenock. He also ran a successful ship and house-building business.

His mother, Agnes Muirhead, came from a distinguished family and was well-educated. Both his parents were Presbyterians and strong Covenanters. Watt’s grandfather, Thomas Watt, was actually a mathematics teacher and bailee to the Baron of Cartsburn. Interestingly given the fact he was raised by religious parents, he would later become a deist.

James’s childhood would be plagued by toothaches and migraines. Because of this medical condition, he was unable to attend school regularly. Owing to this, James was home-taught by his parents initially. His mother taught James how to read whilst his father taught him arithmetic and writing. He would later attend a grammar school where he learned Latin, Greek, and mathematics.

James Watt would show a great level of manual dexterity, engineering skills, and an aptitude for mathematics. Other subjects such as Latin and Greek did not interest him very much.

An important part of James’s education was his father’s workshops. Here James worked with his own tools, bench, and even a forge. He would spend his time at the workshops making models like cranes and barrel organs. He quickly became familiar with the ship’s instruments too.

His time at his father’s workshops helped him quickly decide what he wanted to do with his life, at least at first. During James’s teenage years, his father would lose his inheritance due to commercial disasters and his mother’s death.

James chooses his destiny

At 17 James decided to become a mathematical-instrument maker. James Watt first moved to Glasgow where one of his mother’s relatives lectured at the university. James would also meet Robert Dick whilst in Glasgow. Dick encouraged Watt to master the skill of instrument making by moving to and working as an apprentice in London. James acted on this advice and in 1755 moved to London after finding a willing master to teach him.

That willing master was one John Morgan. He was an instrument maker who agreed to take him on but with little pay. James would end up working long hours continuously in a cold workshop. Because of this, his health declined.

His abilities surpassed John’s other apprentices and he was able to complete his tenure in one year, which normally extended up to seven years. James’s health broke down within a year but he had learned enough to “work as well as most journeymen.” After this time James returned to Glasgow once again.

As James had not completed an official seven-year apprenticeship the Glasgow Guild of Hammerman (the organization that had jurisdiction over an artisan using a hammer) blocked his application despite there not being any mathematical instrument makers in Scotland at the time.

Watt’s situation was helped by the arrival from Jamaica of astronomical instruments that were bequeathed to the University of Glasgow. These instruments required expert attention. Watt managed to restore them to working order and was renumerated accordingly. These instruments were eventually installed in the Macfarlane Observatory. Because of his excellent work on the instruments, three professors offered him opportunities to set up a small workshop within the university.

Setting up shop

This was initiated in 1757. Here he made and sold mathematical instruments like quadrants, compasses, and scales. He would also help with demonstrations. Whilst on the university campus James met many scientists and notably became close friends with the British chemist and physicist Joseph Black.

Joseph would later go on to develop the concept of latent heat. James would also befriend the famed Adam Smith. In 1758 James became acquainted with John Craig, a local businessman, and architect. The two formed a partnership that allowed James to open another shop in Glasgow to sell musical instruments as well as toys.

This partnership lasted for six years and the pair eventually employed up to sixteen workers. Craig sadly died in 1765. One of their employees, Alex Gardner, eventually took over the business which actually lasted well into the 20th Century. In 1764 he married his cousin Margaret Miller, who, before she died nine years later in childbirth, bore him six children.

James’s engine

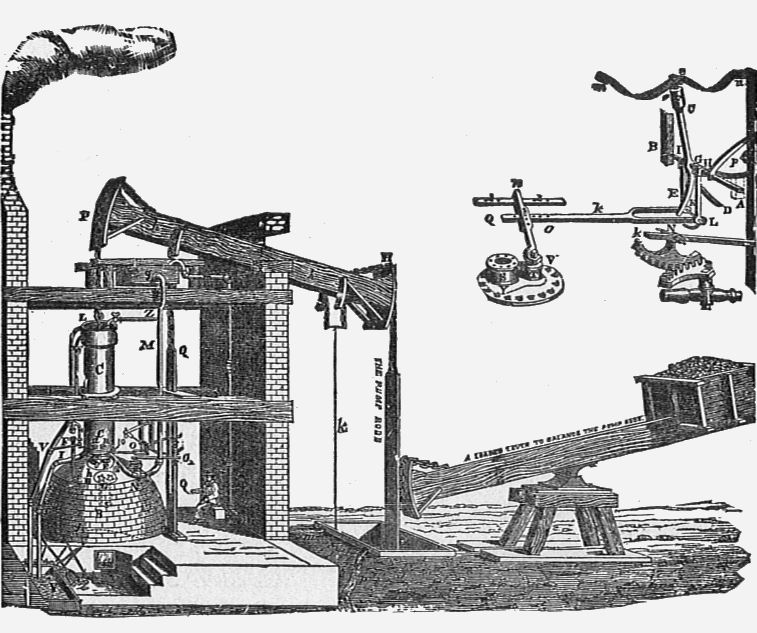

In 1764 James found himself repairing a model Newcomen steam engine. Watt quickly realized just how inefficient the design was, it wasted a lot of steam. James decided to wrestle with the design to improve its efficiency. In 1765 he finally came up with a solution.

The Newcomen engine had been in use for almost 50 years for pumping water from mines. Its design had hardly changed at that time.

James’s idea was to provide the engine with a separate condenser. This was to be his first and greatest invention. Watt had noticed that the problem with the Newcomen steam engine was its loss of latent heat. At this time understanding of the steam engine was in a very primitive state. The science of thermodynamics would not be formalized for at least another 100 years.

James managed to repair the model but it hardly worked. He continued to experiment with it and found that around three-quarters of the thermal energy of the engine were being consumed in heating the engine cylinder on every cycle. This energy was wasted because later in the cycle cold water was injected into the cylinder to condense the steam to reduce its pressure. Thus by repeatedly heating and cooling the cylinder, the engine wasted most of its thermal energy rather than converting it into mechanical energy.

This loss of latent heat was a huge defect with the Newcomen engine in James’s opinion. Watt’s solution would have the condensation effected in a chamber distinct from the main cylinder but connected to it.

James hits on an idea

In 1765, Watt was hit by inspiration. He realized was to cause the steam to condense in a separate cylinder apart from the piston. James also realized that the engine would need to maintain the temperature of the cylinder at the same temperature as the injected steam by surrounding it with a “steam jacket.”

This would mean that very little energy was absorbed by the cylinder every time it cycled. This would produce a considerable increase in the availability of energy to perform useful work.

James would later meet the British Physician, chemist, and inventor John Roebuck. John was the founder of the Carron Works and it was he that encouraged James to make his own engine. James Watt and John would enter into a partnership together after he had made a small test engine. His prototype was made possible by some loans from Joseph Black.

Roebuck lived at Kinneil House, Bo’ness at the time and Watt would work in perfecting the engine in a small adjacent cottage to the house. The cottage’s shell and a very large part of one of his experiments still exist today.

The engine’s progress was stalled because of the difficulty in machining the piston and cylinder for his engine. Ironworkers at the time were more akin to blacksmiths than modern-day machinists. They were, therefore, unable to produce the components with high enough precision.

The following year Watt took out the famous patent for “A New Invented Method of Lessening the Consumption of Steam and Fuel in Fire Engines.” This was pursued at the great cost of capital.

James gets a job

James Watt had become strapped for cash. This forced him to seek out employment. In 1766 Watt had become a land surveyor. The next eight years of his life were consumed marking out routes for canals in Scotland. This work severely ate his time and his work on his new steam engine was severely set back.

His partner Roebuck would sadly go bankrupt in 1772. An English manufacturer and engineer Matthew Boulton who was also the manufacturer of the Soho Works in Birmingham took over Roebuck’s shares in Watt’s patent. After eight years of land surveying, James would become jaded with the task. Partly owing to his new partnership with Boulton, James moved to Birmingham in 1774.

His partnership with Boulton would provide James with access to some of the best ironworkers in the world. This helped immensely with producing parts with enough precision needed for his engine.

James Watt’s engine was an instant hit

James Watt’s patent was extended by the British Parliament in 1775. The same year Boulton and Watt would form a more official partnership that would last for more than 25 years. The financial support that Boulton provided allowed for the rapid progress of Watt’s engine. So fast, in fact, that by 1776 two engines were installed and fully functional.

One engine was delivered and installed to pump water at the Staffordshire Colliery. The other was used for blowing air into furnaces at John Wilkinson’s forges. In 1776 James would also marry again to his new wife Ann MacGregor. She bore him two more children.

Over the next five years, right up to 1781, James Watt would spend long periods of time in Cornwall. Here he installed and supervised numerous pumping engines for the lucrative copper and tin mines of the area. James’s engines had become very sought after as mine managers were looking for ways to reduce costs including fuel costs.

Franchising production

James Watt’s early engines were not manufactured by Boulton and Watt directly. Rather they were licensed out to be made by others following drawings and plans made by Watt. James would often be needed to serve as a consulting engineer for their production. Engine assembly and shakedown were initially supervised by Watt in person. Later by other men in their firm’s employment.

These early machines were pretty big. One of the first, for example, had a cylinder with a diameter of 127 cm and a height of 7 meters. They were required to be assembled in a dedicated building to house them. Boulton and Watt would charge an annual payment for the machines. This was set as 1/3 of the value of coal saved when compared to an existing Newcomen engine performing the same work.

Watt, for all his scientific and engineering acumen, was no businessman. He was obliged to endure keen bargaining in order to obtain adequate royalties on his engines. Despite this, by 1780 James was doing pretty well financially. His partner, Boulton, however, was finding it hard to raise capital. The following year Boulton saw a new market open up in the corn, malt, and cotton mill industries.

Boulton spots new opportunities

James Watt was urged by Boulton to invent some form of rotary motion for his steam engines. The idea was to replace the reciprocating action of the original. In 1781 he did just that. His so-called sun-and-planet gear provided the motion by means of which a shaft produced two revolutions for each cycle of the engine.

In 1782 James was on a roll. He invented and patented the double-acting engine. This engine had a piston that pushed as well as pulled. The engine required a new method of rigidly connecting the piston to the beam.

His solution was developed in 1784 when he invented parallel motion. This is an arrangement of connecting rods that guided the piston rod in a perpendicular motion—which he described as “one of the most ingenious, simple pieces of mechanism I have contrived.” Boulton would later suggest the need for the centrifugal governor for automatic control of the speed of the engine. Watt would take on his suggestions and apply them successfully in 1788. By 1790 he also invented and added a pressure gauge. This virtually completed what we know today as the Watt Engine.

Later years

Orders quickly flooded in for his engine from paper mills, flour mills, cotton mills, iron mills, distilleries, canals, and waterworks. So many, in fact, that by 1790 Watt had become a wealthy man. He had, to date, received around £76,000 in royalties from his patents over the preceding 11 years. His later years were not wholly consumed by his steam engines, however.

James Watt was a member of the Lunar Society in Birmingham. This was a group of writers and scientists who wished to advance the sciences and arts. Watt would also spend his time experimenting with the strength of materials. James was also often involved in legal proceedings to protect his patents.

In 1785 Watt and Boulton were elected as fellows of the Royal Society of London. He would also begin to spend time on holidays. He even bought an estate in Doldowlod, Radnorshire. By 1795 Watt began to slowly withdraw from the business. By 1880 James was fast approaching retirement age. 1880 also happened to be the year that his patents and partnership would start to expire.

Watt established a new firm in 1794, Boulton and Watt. This enterprise built the Soho Foundry to manufacture steam engines more competitively. It was also around this time that Watt’s son from his first marriage, James, began to give him problems.

Family problems

James Watt Junior was a young sympathizer for the French Revolution. He had been openly criticized in Parliament for presenting in 1792, an address from the Manchester Constitutional Society to the Société des Amis de la Constitution (the Jacobin Club) in Paris.

Watt’s long retirement was later also saddened by the sudden death of another son by his second marriage, Gregory. He would also outlive many of his old and closest friends. Despite this, James traveled to Scotland, France, and Germany when the Treaty of Amiens was signed in 1802.

James Watt would continue his work in the garret of his house. Here he had built and equipped it as a small workshop. James continued to tinker and invent and actually developed the sculpting machine with which he reproduced original busts and figures for friends.

James also operated as a consultant to the Glasgow Water Company. Watt’s achievements were amply recognized in his lifetime. He was made a doctor of laws of the University of Glasgow in 1806 and a foreign associate of the French Academy of Sciences in 1814 and was offered a baronetcy, which he declined.

Death and legacy

James Watt died on the 25th of August, 1819. He was 83 years old.

James Watt’s steam engine was a truly groundbreaking development and, arguably, the key to the Industrial Revolution. His machine became incredibly popular and was installed in many businesses across the United Kingdom. Such was his contribution to science and technology that a unit of power was named in his honor, the Watt.

The Watt, in case you are unaware, is an SI unit equal to one Joule of work performed per second. This equates to about 1/746 of a Horsepower (for mechanical and electrical horsepower). Some scientists also argue that the invention of his parallel motion (or double-acting engine) in 1784 should mark the beginning of the controversial Anthropocene Epoch. This is an as-yet unofficial interval of Geological Time.

In May of 2009, the Bank of England announced that Boulton and Watt will appear on the new £50 note. This design is the first to feature a dual portrait on any Bank of England note. This image featured the two men, side by side, juxtaposed with images of the Watt’s steam engine and Boulton’s Soho works. Quotes attributed to each of the men are inscribed on the note: “I sell here, sir, what all the world desires to have—POWER” (Boulton) and “I can think of nothing else but this machine” (Watt).

RECOMMENDED ARTICLES

In 2011, James Watt was also one of seven inaugural inductees to the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame.

The Blueprint Daily

Stay up-to-date on engineering, tech, space, and science news with The Blueprint.

By clicking sign up, you confirm that you accept this site's Terms of Use and Privacy Policy

ABOUT THE EDITOR

Christopher McFadden Christopher graduated from Cardiff University in 2004 with a Masters Degree in Geology. Since then, he has worked exclusively within the Built Environment, Occupational Health and Safety and Environmental Consultancy industries. He is a qualified and accredited Energy Consultant, Green Deal Assessor and Practitioner member of IEMA. Chris’s main interests range from Science and Engineering, Military and Ancient History to Politics and Philosophy.

0