In the months, then years, after the Christchurch earthquake, it was not Sue Spigel’s mind that needed healing, but her spirit.

What worked was her home high on the hillside above Governors Bay, where Spigel, 74, and her husband, Bob, have lived for 20 years. “It was this place … being here, cocooned from the rest of the agony that was going on, that really helped,” she says, sat with her back to a large window framing bush, sky and sea.

On 22 February 2011, Spigel had been at the Christchurch cathedral, where she was artist-in-residence. Her tiny first-floor workshop was reached by a spiral stairwell so narrow it would leave her shoulders dusted with chalk.

At 12.51pm, Spigel had been about to go down those stairs to make a cup of tea when she was distracted by a radio news report. She sat down on the window seat. “The building shook a little bit, and I thought, ‘That was a good one’,” she says. “But then it began bouncing up and down.”

Spigel saw the ceiling come free from the walls, flickering light from the outside; she felt blood streaming from her head. “Then the tower fell, that huge piece of masonry, and it was like a tornado. Black dust everywhere – I couldn’t breathe.”

When the black cloud cleared, it revealed “an alternate reality”.

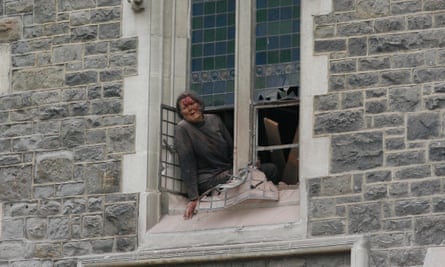

The floor had fallen through, and she was buried in ceiling boards. Though her arm was broken, Spigel managed to push herself onto the window ledge. A few hundred people were standing in the square below, staring back at her. “Everybody was just stunned.”

She was rescued by a police officer, who clambered over piles of rubble to get to her. He and others then helped her climb down a ladder to safety.

The falling tower had caused major damage to the front of the cathedral, its western porch and adjacent walls. It took search and rescue teams more than a week to confirm that – miraculously – no one had been killed inside.

In that time, images of Spigel hanging out of the cathedral, bloody and dazed, had travelled the world. Even now, within Christchurch, she is still known as “the woman in the window”.

A symbol of wider trauma

Spigel became the face of the damage done to the cathedral, and with it the city’s spirit. Of all the buildings lost that day, its collapse had the greatest resonance.

The 19th-century neogothic structure had been Christchurch’s namesake and defining symbol, down to the local government’s logo. It was not just the home for the city’s Anglican diocese – it was often spoken of, figuratively and literally, as the “heart of the city”.

For Spigel, it had been her first sanctuary in Christchurch. She and Bob had moved from the US in the early 1980s, but it was not until an anniversary service for 9/11 that she connected to the cathedral.

“For the first time, I felt like I really belonged in Christchurch … I loved the structure, the pageantry, the art about the whole place – and the fact that it welcomed anybody.”

Designed by the English architect Sir George Gilbert Scott (also behind London’s St Pancras Station), the cathedral has been described as “among the most perfect symbols of the reach and ambition of the Anglican confession worldwide”.

The sight of it tumbled into rubble, its tower toppled, was immediately understood as symbolic of the wider trauma and loss suffered by Christchurch and its people in the earthquake.

The cathedral dean Peter Beck told the BBC at the time: “The heart of the city is broken.” Bob Parker, then the mayor, vowed to rebuild the cathedral “stone by stone”: “We’ve lost a lot of things, but that is one we should not lose.”

Instead, for nearly 10 years, the cathedral has languished – open-faced, piled with rubble, too risky to enter – as new buildings have sprung up around it: an unmistakable reminder of the earthquake, even as Christchurch has sought to move on.

How to rebuild?

If the symbolism of the collapsed cathedral was clear, the challenge – once the dust settled and the rebuild got under way – lay in how to interpret it.

The church, city council, central government, business leaders, heritage advocates, architects and artists – not to mention the 250-odd regular worshippers – agreed on the building’s significance but not, necessarily, what to do with it.

Various options – including reinstating the cathedral exactly as it was, rebuilding it to a new design, and demolishing it and starting over entirely – were explored and often hotly debated.

Ultimate responsibility rested with the building’s legal owners, the Church Property Trustees, chaired by the Canadian-born Bishop Victoria Matthews. For her, spending church coffers (or fundraising) to repair a single building went against the “Christ-centred mission”.

In March 2012, Matthews announced that the cathedral would be replaced with one that was a “mixture of old and new”.

The news was met with vociferous opposition from Christchurch residents who felt attached to the historic cathedral, and that its fate was not the church’s call alone to make.

Many were of means and influence, such as the former government minister Philip Burdon and the late mayoral candidate Jim Anderton, who formed a nonpartisan protest group Great Christchurch Buildings Trust (GCBT).

The standoff came to a head in November, when the High Court granted an application by GCBT for a judicial review of the diocese’s decision to demolish, halting all work under way.

The fight over the cathedral reflected tensions prevailing in the city at the time, such as between local and central government, says Ian Lochhead, an architectural historian and visiting associate professor at the University of Canterbury.

He had been one of the first voices to speak up for Christchurch’s historic buildings after Gerry Brownlee – the National-led government’s minister for earthquake recovery, granted substantial power in the rebuild – declared that the “old dungas” [sic] would be destroyed.

“There was a widespread belief that the city had performed poorly in terms of its seismic resistance, and so it would be replaced,” says Lochhead.

In its eagerness “to get everything back to normal” – bulldozing heritage buildings that could have been saved, encouraging commercial development, throwing out public consultation for plans made in haste – the central government was seen to be sacrificing Christchurch’s identity.

The sense of urgency was not only unrealistic, says Lochhead, it led to demolitions “that didn’t need to happen, just because people wanted it all tidied away”.

Now, he says, “hardly any” of Christchurch’s 19th- and 20th-century faces can be seen in the central city – while there are more large, high-end commercial developments than can be kept at full occupancy.

Lochhead calls this “crisis capitalism” in action. “We went from a city that had a fine grain to … a smaller number of much bigger buildings. It’s completely transformed the feel of the city.”

Those losses galvanised some who were fighting to save the cathedral – but not before the bitter debate over it had made others lose faith in its significance entirely.

Forgetting the past

Mired in indecision, infighting and politics, what had once been a symbol of strength for the city became symbolic “of all that was wrong with the rebuilding”, as a longstanding member of the congregation wrote in 2015.

Even Spigel felt like she had to guard against a congregation – and a cause – she had cherished, switching for a time to the progressive Knox Presbyterian church.

“I had to take care of myself,” she says. “So I just turned my back.”

Spigel had little need, or desire, to go into the city with its new, glass buildings. “I don’t find it welcoming, or pleasant, at all.”

She says it reminds her of a sermon she heard once, about Alzheimer’s disease: “When you forget your past, you can’t put yourself in context, and you have no idea who you are – I feel like that’s what’s happened in Christchurch.”

Eventually – through fluctuating public opinion, a protracted legal action and even attempts at mediation – in September 2017 the Anglican Synod voted to reinstate the cathedral.

Once a government working group had found that outcome to be possible, “from the church’s point of view, they were confronted by an insoluble problem”, says Lochhead.

Being nowhere close to covering the projected $100m cost of the project alone (it was subsequently revised to $150m), financial support from central and local governments and GCBT was an offer the Church Property trustees could not refuse.

In August 2018 it signed a joint venture agreement with Christ Church Cathedral Reinstatement Limited (CCRL), a government entity set up to deliver the project with a separate fundraising arm. (Lochhead is a trustee.)

“It was a marriage of two warring parties … there was always going to be some feeling around that,” says Keith Paterson, the project director of CCRL.

But finally, a decade after the disaster, a path forward has emerged that – he hopes – will help the city and its people to heal. “If we could fix the cathedral and revitalise the square, it does draw a line under the earthquakes ... The city will breathe a sigh of relief.”

Just six months ago, the cathedral had looked abandoned; there now are signs of life in the heart of the city, with construction crews on cranes working to make the site safe to return to its former glory.

Their brief is to return the cathedral to “as it was before”, but safer, with more modern facilities and two new buildings for visitors and events.

But when no one has entered the cathedral since 2011, merely stabilising the site is an enormous endeavour. Paterson is under no illusion as to the scale of the project, expected to take seven to 10 years to complete.

“For me there was a part of the city that was basically broken, and it needed help … It was the civic aspect of the building that drew me to it – and the challenge.”

Of course a new cathedral would have been cheaper, he says; but cost is not the only concern. “You’ve got to put a value on heritage, on symbolism.” (Paterson’s own ancestor has a memorial plaque within the cathedral.)

The challenge, now, is fundraising – with $50m needed to ensure continuous construction. Philip Burdon alone has now contributed $5m, but in asking wider Christchurch to get behind the cathedral, after 10 years the trust expects to have to battle a level of fatigue.

It is hoping to draw on Christchurch’s strong English connection by targeting heritage and Anglican interests in the UK. Prince Charles is a “royal patron” of the project.

“The design that we’ve come up with will rejuvenate the square, not only as a great place for worship but as a great civic space,” says Paterson. “… I’ve got no doubt that the outcome will be excellent – if people can be a little bit patient.”

In the context of heritage preservation and even disaster recovery, experts say, 10 years of debate and 10 years of construction is negligible. But at the start of this next stage, questions are being asked within Christchurch as to where it will lead: into the city’s future, or its past.

Naomi van den Broek, an musician and performer active within the arts sector, says the cathedral has been “held to ransom” by members of the Christchurch establishment, and denied the opportunity to evolve alongside the rest of the city.

Restored to its prior state, the cathedral will be “a souvenir, or a museum piece”, says van den Broek: a missed opportunity to build a “beautiful talking point … that looks forward as well as back”.

But Te Maire Tau, the director of the University of Canterbury’s Ngāi Tahu Research Centre and a trustee of the reinstatement project, says he understands the “Pākehā tribalism” that was provoked by the threat of losing the cathedral. “You had old Christchurch saying ‘This is who we are, this is what we are … we’re still here, we exist’, and I thought, from our end, that was something to be respected.”

At a time when Christchurch risks losing its identity, it is important to recognise that connection to the past, and the city’s European history, says Tau. “People live on symbols … there’s that hole in the square. The church needs to be there.”

Certainly, the central construction site is a daily reminder of the earthquake when many in Christchurch feel that it no longer defines them.

For Spigel, the trauma of that day and the lives that were lost still lies “just beneath the surface”.

“I’m waiting for the cathedral to be reinstated – I just hope it’s done before I die. I would love to go back in there … to hear music, the bells ring again.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion