Article by: Adam Manning

Edited by: Harry T. Jones and J. D. Dixon

Australia is world-famous for its opal mines, producing 80% of the global supply of the precious gemstone. But many of the miners who work there are keen-eyed and have noticed something else within the pretty rocks: fossils, encrusted or sometimes even made completely out of opal.

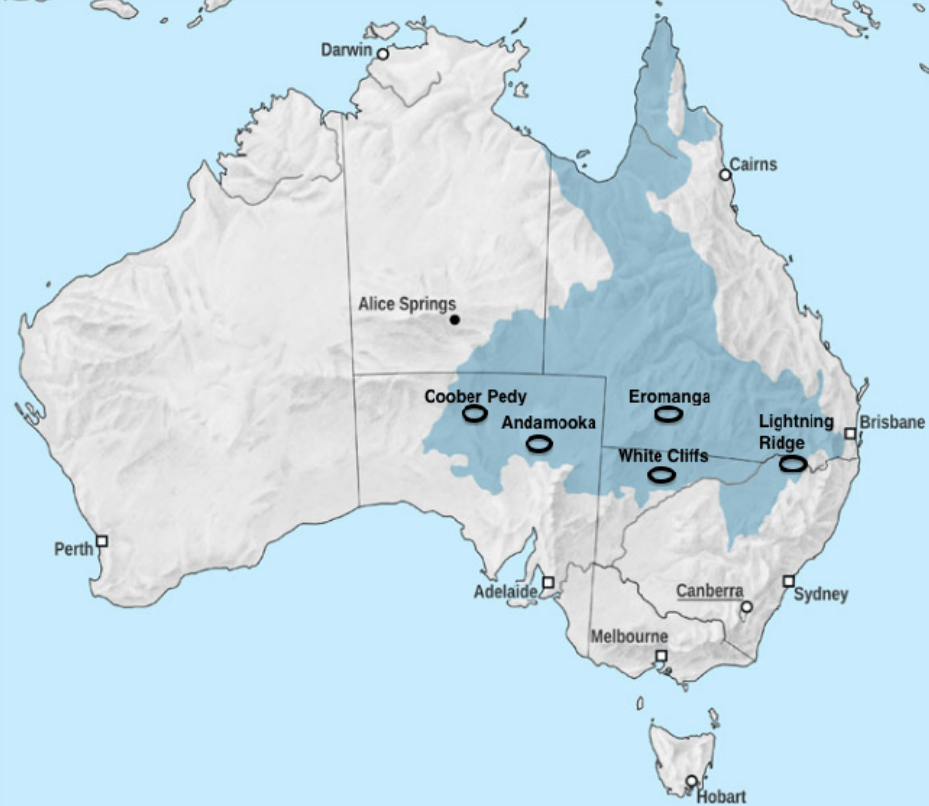

The opal fields of Australia date back to the Cretaceous Period, approximately 100 million years ago, and their fossils come from a wide variety of palaeoenvironments. Whilst places like Lightning Ridge produce terrestrial and freshwater fossils, fossils from White Cliffs and Coober Pedy are mainly marine. This is because in the Cretaceous, a large inland sea known as the Eromanga Sea covered nearly a third of the country.

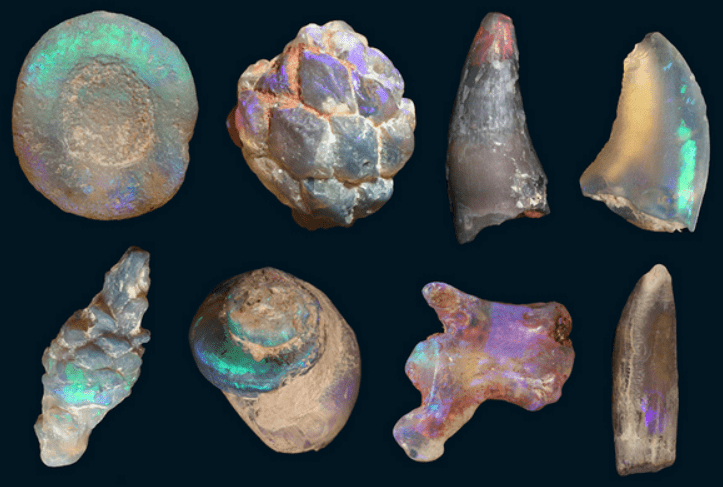

There are many opalised fossils known from Australia, including molluscs, echinoderms, wood fragments, pine cones, as well as vertebrate bones, including dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and crocodilians. In fact, the opalised fossils that can be found are so diverse that the ecological fauna of the Eromanga Basin can be reconstructed using just these. The beautiful fossils that these sites produce are also of scientific importance. The opal fields at Lightning Ridge have yielded the oldest eel skull in the world, preserved in opal, as well as the remains of the oldest horned turtles.

So how do these amazing fossils form, and why are they so common only in Australia? Opal’s chemical formula is SiO2 nH2O, otherwise called hydrated silicon dioxide. The Eromanga Sea that stretched across Australia acted as a basin for volcaniclastic sediments that were eroded into the basin. The sea was also shallow, cold, and poorly connected to the ocean, preventing carbonates from forming. These unique conditions allowed opal to form. When an animal dies in this type of environment, it is buried, and over millions of years, fossilises just like any other fossil. However, in the case of the opalised fossils, the fossils then disintegrate and the silica-rich water fills the mould left behind. When the water eventually evaporates it leaves behind silica gel in clumps which then harden. The fossil has then been opalised. In some cases the fossil doesn’t disintegrate, and instead the opal infiltrates small cavities in the fossil, preserving its internal structure. The kind of opal that is produced depends on the arrangement of the silica spheres within the fossil.

The opalised fossils of Australia are a unique, beautiful time capsule of life in the Cretaceous seas of the continent. There are still many more fossils that are yet to be collected and/or described, so we are looking forward to what the future may bring from these incredible finds.

Image References

[1] Various opalised fossils from Australia. Image taken from Voiculescu-Holvad (2018).

[2] Map of the Eromanga Inland Sea, which covered part of Australia during the Cretaceous. Image taken from Voiculescu-Holvad (2018).

[3] A) Collection of Dromaeosaurid teeth. B) The well-preserved skull of the turtle Spoochelys ormondea in dorsal and ventral views, respectively. Scale bar: 20 mm. C) Opalised pinecones. Figure compiled from Voiculescu-Holvad (2018) by Adam Manning.

Information References and Further Sources

Rey, P. F. (2013). ‘Opalisation of the Great Artesian Basin (central Australia): an Australian story with a Martian twist’, Australian Journal of Earth Sciences, 60 (3), pp. 291-314. Accessed 22nd February 2021. Click Here.

The National Opal Collection. (Unknown). ‘Opalised Fossils and Specimens’. Accessed 22nd February 2021. Click Here.

Voiculescu-Holvad, C. (2018). ‘The Opalised Fossils of Australia: Mineralogical and Paleontological Treasures from the Australian Outback’. Accessed 22nd February 2021. Click Here.

Watson, C. (2019). ‘Scientists and Miners Team Up to Preserve Opalized Fossils’, Smithsonian Magazine. 1st August 2019. Accessed 22nd February 2021. Click Here.