Editor’s Note: Paul French is the author of books including “Midnight in Peking: How the Murder of a Young Englishwoman Haunted the Last Days of Old China,” and “Through the Looking Glass: China’s Foreign Journalists from Opium Wars to Mao.”

Northeast of Beijing’s resplendent Summer Palace lie the ruins of another stately structure, burned to the ground by European forces during the Second Opium War.

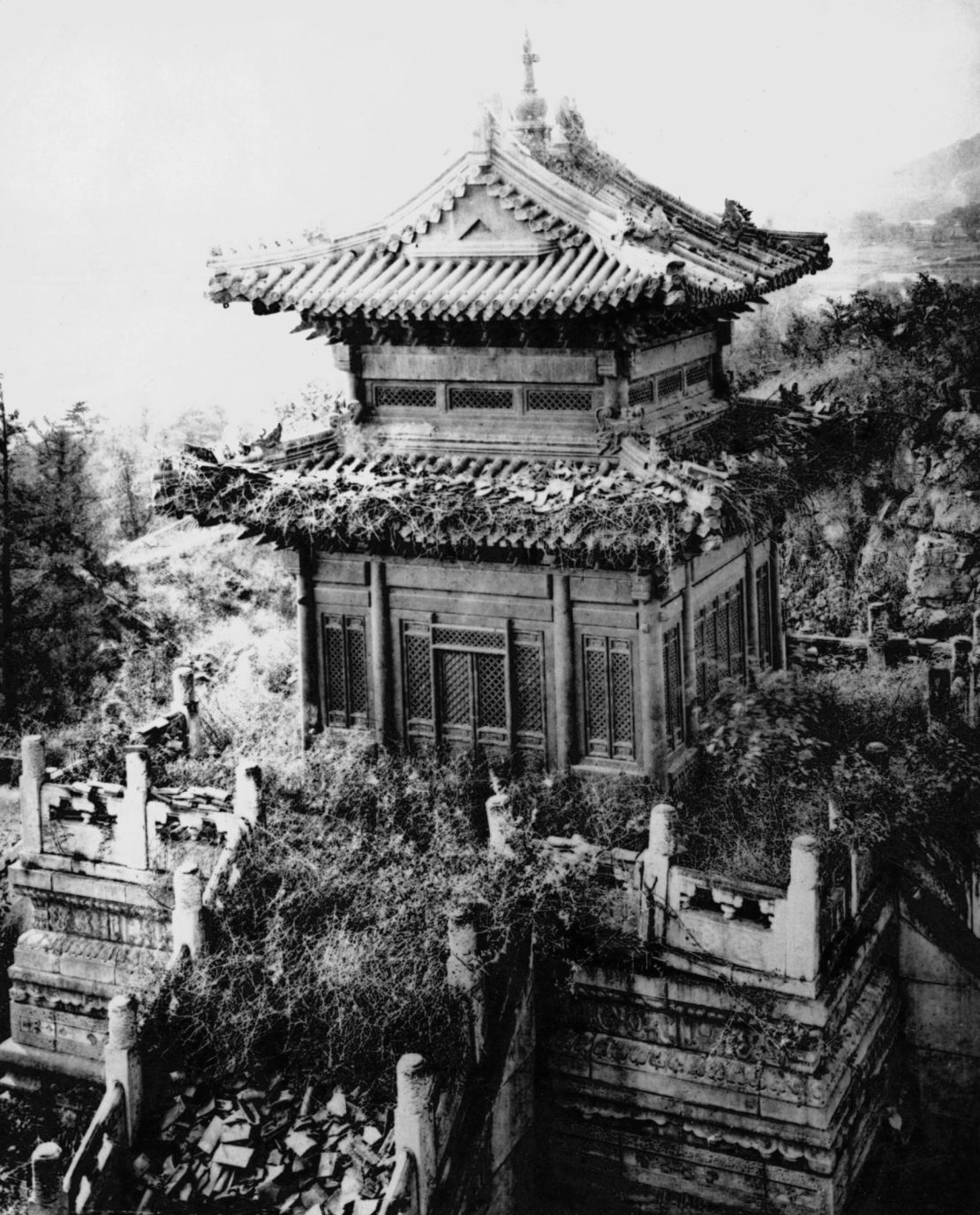

Once an elaborate network of pavilions, palaces, bridges and gardens, Yuanmingyuan – “The Garden of Perfect Brightness,” known simply as the Old Summer Palace in English – is now little more than collections of rubble amid a network of tranquil lakes. In 1860, Britain’s High Commissioner to China, Lord Elgin, ordered troops to destroy both the Summer Palace and Old Summer Palace to avenge the killing of several British envoys to Beijing. By striking sites of cultural and imperial significance, Elgin wanted to chasten China.

But with the Old Summer Palace still in ruins, he instead created a shrine that, more than a century on, is used by the country’s leadership to remind its people of past foreign aggression.

Each year, tens of thousands of visitors arrive to see its broken pillars and stone bricks, which dot an unkempt landscape of grass and weeds. They are potent symbols of China’s “century of humiliation,” the term Beijing uses to describe the period from the start of the Opium War in 1839 to the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949.

Over the decades, scholars and experts in China have suggested that the palace be rebuilt in order to celebrate the grandeur of China’s past, thus banishing, rather than indulging, the memory of subjugation. The site could, ultimately, emulate the success of the neighboring Summer Palace, which was since rebuilt and has become one of China’s most popular visitor destinations.

However, the National Cultural Heritage Administration (NCHA), the government agency responsible for protecting cultural relics, ruled out the latest restoration proposal in November.

The site’s value lies in its “historical status of being destroyed by foreign aggressors,” the agency said in a statement. “The site and its ruins serve as a warning to our descendants that they shall never forget the national humiliation.” In a country where vestiges of the past are either zealously restored to their former glory or cleared to make way for new developments, the decision to leave the palace in ruins is conspicuous in its inaction. To some critics, the announcement was both a pointed political gesture and a symptom of patriotism that is not simply pro-China, but anti-foreign.

A masterpiece of design

From the early 18th century, the Old Summer Palace grew into an exclusive getaway resort for the ruling elite of China’s Qing dynasty. Its architectural splendor has since been compared to France’s Palace of Versailles.

“It was actually a combination of five garden residences of the Qing emperors,” said Ying-chen Peng, a professor and Chinese art specialist at Washington D.C.’s American University, in a phone interview. “And in each garden residence, you have clusters of buildings and even artificial lakes, ponds and water systems. It really was a gem of Chinese architecture.”

Although construction started during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor in the early 1700s, the complex underwent a major expansion under his grandson the Qianlong Emperor’s rule. As well as increasing the complex in size, he also sought to diversify its architecture, which until then was typical of the country’s north, according to Peng.

“He treated it as a miniature (version) of his empire. He made several trips to southern China … and he was enchanted by its beauty,” she said of the emperor’s so-called “inspection tours,” during which he would visit temples and mausoleums on official business as he consolidated power across the vast empire. “After he returned from these trips, he would order his architects to replicate famous scenes or sites that he had seen and appreciated.”

Examples offered by Peng include Ruyuan (Garden of Ease), a replica of a garden in China’s former capital, Nanjing, and Anlanyuan (or Tranquil Wave Garden), which was based on a garden of the same name in Haining, Zhejiang province.

More unusually for the time, Qianlong also commissioned Jesuit missionaries to design several European-style palaces and fountains. These structures represent what Peng called “hybrid” architecture, which saw Western stone facades built over traditional Chinese wooden frames. (Because stone has proven more durable than wood, the remains of these Italian baroque-style buildings are now among the most prominent of the Old Summer Palace’s ruins, despite constituting a small minority of the original structures).

“Even though they were missionaries, they were actually sort of ‘Renaissance men’ by training – musicians, painters or even engineers,” Peng said. “So, for the court, they were not treated as missionaries, but as people who could realize the Emperor’s fascination with exotic cultures.”

The palace also served as a storage site for some of the nation’s most treasured art and artifacts. When Anglo-French soldiers arrived on Elgin’s orders to ransack it, they stole many of the items before burning the buildings to the ground. Perhaps most famous among the looted treasures were a dozen bronze animal heads, representing the 12 animals of the zodiac, which China has long sought to reclaim from overseas. (More than half have now made their way back to the country via auctions and donations, with their return often depicted in Chinese media as something of a national quest – and even inspiring a 2012 Jackie Chan action movie on the subject. Five of the statues remain missing to this day.)

Meanwhile, the nearby Summer Palace (sometimes called the “new” Summer Palace, to avoid confusion) has benefited from multiple rebuilds since being ransacked. Nearly 30 years after the initial assault, Empress Dowager Cixi, then China’s de facto supreme leader, ordered some of its damaged imperial structures to be rebuilt, and gave them the name Yiheyuan (“Garden of Good Health and Harmony”).

The revamped complex and its lavish gardens survived further turmoil and were added to UNESCO’s World Heritage List as a “masterpiece of Chinese garden landscape design” In 1998. The Old Summer Palace, however, was left to stagnate.

Restoration debate

By the early 20th century, the Old Summer Palace had become a repository for building materials. Nearby structures were often made from, or at least decorated with, debris taken from the ruins. During Mao’s rule, which saw famines associated with the disastrous Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution campaigns, farmers encroached on the land in desperate attempts to grow more food. It later became known as a place where artists lived and worked in the 1980s and early 1990s – or “squatted,” as the authorities saw it. They were eventually kicked out.

Since the start of China’s reform era in the late 1970s, however, a number of grand plans have been floated to restore the Old Summer Palace. In 1984, a proposal to partially restore several pavilions emerged, and in the 1990s, there were also plans to use foreign investment to fund a miniature replica of the Old Summer Palace on the site, though neither scheme transpired. A restoration plan was finally approved in 2000, though archeological and environmental experts were “quick to denounce it,” according to a 2006 editorial in the Australian National University’s China Heritage Quarterly.

“The contretemps about whether the park be preserved as it was, partially restored, partially rebuilt or fully restored raged in the print media for some months, and every time a new incident involving the gardens occurs the familiar battle lines are redrawn and the debate unfolds anew,” it read.

The latest reconstruction proposal was championed by Yan Jianguo, a Beijing-based lawyer and delegate in China’s legislature, the National People’s Congress (NPC). In May 2020, at the NPC’s annual meeting, Yan argued that his vision for the project, which would include the extensive restoration of buildings and gardens, was essential for “educational and patriotic purposes.”

China’s leaders did not agree. And neither, perhaps, would the Chinese public. Although conducted around a decade ago, before the most recent rebuild proposal had emerged, an online poll by Sina news found that 77% of respondents opposed a rebuild, with many reportedly citing the potential cost of the project.

Having said that, price concerns have hardly been prohibitive when it comes to major heritage projects in China. For instance, since 2005, the central government has allocated 1.9 billion yuan ($294 million) to a long-term project to restore the Great Wall section by section. The entire ancient town of Dukezong in Shangri-la county, Yunnan province, was meanwhile rebuilt at a cost of 1.2 billion yuan ($186 million) after a 2014 fire, according to Chinese state media.

But the expense involved in rebuilding the entire Old Summer Palace could be uniquely astronomical. In 2008, a full-size replica of the complex – essentially a large movie set with some surrounding landscaping – was built at Hengdian World Studios in Zhejiang province at reported cost of 30 billion yuan ($4.6 billion). And restoring the Beijing original would be “definitely more expensive than that,” Peng speculated.

Looking to the future

For Peng, the debate is not merely about whether to restore the palace, but how it might be done. She welcomed the rejection of the most recent proposal on the grounds that too many questions remain unresolved.

“When we talk about reconstruction in architecture, it’s actually a package. It is not only about the structures per se,” she said.

“How do we deal with the interior?” she offered as an example. “Are we going to leave it empty, or are we going to try to replicate the interior design and furnish it with authentic items? If the project is to pursue that path, it would definitely be much more expensive and also controversial, because to what degree can we then call it an authentic construction?”

Other proposals have suggested simply building a museum to display and protect some of the treasures once housed at the palace. One structure on the site, the old Zhengjue Temple, was in fact recently rebuilt in order to exhibit one of the returned zodiac animal heads, while other government efforts have focused on landscaping and renovating the man-made lakes.

Writer and historian of the Qing dynasty Jeremiah Jenne, who has been based in Beijing since 2002 and regularly visits the Old Summer Palace with students, believes that a complete rebuild is not required. But, he said, the history of the ruins could nonetheless be better explained to visitors. There is no central plaque or memorial, he noted, suggesting this could be achieved using virtual reality technology, which many museums are now using worldwide.

“Ruins have power, allowing you to use your imagination, which can add poignancy to the visitor experience,” he said.

Experts from Tsinghua University have gone some way toward recreating the Old Summer Palace in digital form. According to state media, researchers studied more than 10,000 historical files to make more than 4,000 design charts and 2,000 digital architecture models. Combined, they show at least 60% of the original structure.

This kind of digital reimagining may be as close as we can get to experiencing the original splendor of the imperial complex, given that the most recent proposal for the Old Summer Palace – among the most extensive and ambitious plans to restore the ruins to date – appears to be dead in the water, But it probably won’t be long before another plan surfaces and reignites the debate of what to do with the site, and how to reinterpret China’s “century of humiliation.”

“I’m just glad that we have seen the dimension of the discussion grow more and more diverse,” Peng said, “because in the ’80s and ‘90 it was just seen (in terms of) the shame of China’s past. Now, there’s a new take that sees it as (part of) the glory of China in the 18th century … so it will be interesting to observe how it will be discussed in the future, and how those discussions reflect the Chinese mentality.”