The history of a city is nothing without the people who live in it. But some people stand out more than others! Sydney’s history is populated with colourful and eccentric characters, among them Arthur Stace and Bea Miles.

Bea Miles was born into a wealthy Sydney family in 1902, first living at Ashfield and later moving to the northern Sydney suburb of St Ives. Bea went to Abbotsleigh, a private girls school, and later attended Sydney University where she enrolled in medicine. She later changed to an Arts degree because she ‘couldn’t stand the type of young men who were doing medicine’.

In the early 1920s, Bea was committed to the Gladesville Asylum at the behest of her father, but was later released following a strenuous campaign by Sydney tabloid paper, the Smith’s Weekly. She was a tall and good looking girl, with a reputation for travelling around the city on a men’s bike wearing a ball gown while blowing a police whistle, and jumping onto the bonnets of taxis and cars. Eccentric? Or just an early incarnation of performance art?

Bea travelled around Australia in the 1930s, getting herself arrested for various minor offences along the way, including recklessly riding a bicycle in Melbourne in 1933, travelling without a train ticket in Bundaberg in 1934, and slapping the face of surf lifesaver in 1938.

It wasn’t until the 1940s and 50s that Bea Miles really hit her stride as an eccentric identity in Sydney. By this time, she cut a distinctive figure around the city streets, with her green ‘tennis eye shade’, a baggy coat safety pinned together at the neck, and a cigarette constantly dangling from her mouth. She was the ‘scourge of cabbies, cops and bus conductors’ according to one Sydneysider who had a run in with her, Clive James.

By this time, Bea had developed a reputation for lobbing into the passenger seats moving taxis as they sped past (and sometimes into the laps of unsuspecting passengers). She also didn’t believe in paying for fares, so she didn’t, which often resulted in altercations.

Bea was homeless for most of the period from the 1940s through to the 1960s, sleeping rough in the bandstand at Belmore Park and in a stormwater drain at Rushcutters Bay. This situation changed in the 1960s when she went to live at the Little Sisters of the Poor at Randwick, even though she had been an avowed atheist all her life. She died in 1973, but was not forgotten, with Australian novelist Kate Grenville writing Lillian’s Story in 1984, based on her life.

Arthur Malcolm Stace was born in Sydney in 1885, the second youngest son of Mauritian immigrants. Stace’s parents were chronic drunkards and by the age of 12, he was a ward of the state. His sisters were prostitutes, and his brothers were also alcholoics.

Out on his ear, Stace took up a variety of jobs including as a coal miner, as a ‘cockatoo’ at a two-up den and as a sly grog runner. Like his parents and siblings, Stace became a chronic alcholic; he also spent time in the Callan Park Asylum for the Insane and had a number of spells in gaol. When he was 31 years old, Stace enlisted in the First World War, serving in the 19th Infantry Battalion. He returned to Australia gassed, and blind in one eye, and took to the bottle again soon after.

.

.

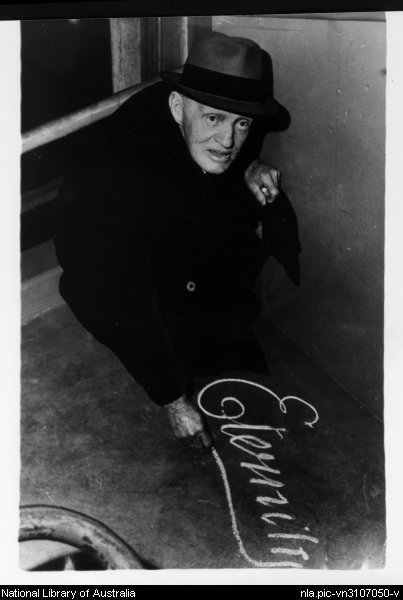

Stace found salvation in 1930 when he attended St Barnabas Church on Broadway. He vowed thereafter to stop drinking. Later that same year, Stace was inspired by the words of Rev. John Ridley who was giving a sermon at the Burton Street Tabernacle in Darlinghurst. Ridley’s rallying cry that he wished that could ‘shout eternity through the streets of Sydney’ inspired Stace to take to the streets with a piece of chalk.

Thus began Stace’s covert career as a pavement scribe / street poet, although his secret identity would be uncovered in 1956. Every day for over thirty years, he set out in the early morning to write the word Eternity over and over in flowing copperplate on the pavements of Sydney’s streets. He was said to have written the word over a million times. Not bad for a man who was virtually illiterate.

Stace died in 1967. And while his chalk markings have long left the city streets, his legacy lives on in the imagination of Sydneysiders, inspiring a movie, a radio play and the celebrations for the Sydney Olympics in 2000.

You can read more about Stace and Miles in Ratbags by Keith Dunstan, 1979.