Renaissance is Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528). We know his life better than the lives of other artists of his time. Dürer traveled, and  found, he says, more appreciation abroad than at home. The Italian influence on his art was of a particularly Venetian strain, through the great Bellini, who, by the time Dürer met him, was an old man. Dürer was an extraordinarily learned person, and the only Northern artist who fully infused the sophisticated Italian dialogue between scientific theory and art, creating his exposition on proportion in 1528. Even though we know so much about his doings, it is not easy to fathom his thinking.

found, he says, more appreciation abroad than at home. The Italian influence on his art was of a particularly Venetian strain, through the great Bellini, who, by the time Dürer met him, was an old man. Dürer was an extraordinarily learned person, and the only Northern artist who fully infused the sophisticated Italian dialogue between scientific theory and art, creating his exposition on proportion in 1528. Even though we know so much about his doings, it is not easy to fathom his thinking.

Albrecht Dürer was born in the imperial free city of Nuremberg on May 27,1471, at a time when the city was shifting from its Gothic past to a more progressive form of Renaissance Humanism. Dürer’s father, a goldsmith, departed Hungary to come to Nuremberg, where he met and married Albrecht’s mother — Barbara Hopkins. At age 13, Dürer accomplished an artistically precise and meticulous silverpoint, entitled “Self Portrait at age 13.” This work of art not only reveals his premature aptitude as a youth, but the unique details of northern art. Albrecht Dürer was first apprenticed to his father at age 14, during which time he learned techniques in metal working. It would be these techniques and his own intrinsic talents that provide a stable base for his future engraving masterpieces.

Dürer, who did not care for goldsmithing, was apprenticed to one of his fathers’ close friends, painter and book illustrator Michael Wohlgmuth, in 1486. While an apprentice under Wohlgemuth, Albrecht acquired the essential skills needed in painting, drawing, and the craft of woodcut. Michael Wohlgemuth’s workshop was extremely busy and was aggressively designing and fabricating woodcuts used in the making of books with detailed illustrations. It is believed that Albrecht may have assisted in the preparation of illustrations in the Nuremberg Chronicles (1493, Hartmann Schedel). This project would have allowed Dürer to view works by the leading printmasters of the period, including Martin Schogauer, the Housebook Master, and other Italian artists.

Albecht Dürer left Michael Wohlgemuth’s studio in 1490 after finishing his apprenticeship to go on Wanderjahre (wandering journey). The main purpose of Dürer’s journey was to visit Martin Schongauer in Colmar. It is believed, however, that he first went to visit the Housebook Master working in the middle Rhine area, after which he continued on to the Netherlands. In 1492 Albrecht sadly discovered that Schongauer had recently died; nonetheless, the master’s brothers welcomed Dürer.

Shortly after, Albrecht went onto Basel to work with another of the Schongauer brothers. During this time he also made many contacts. In Basel and later in Strasbourg, Dürer created illustrations for various publications, in addition to Sebastian Brant’s Das Narrenschiff (Ship of Fools, translated 1507) in 1494. At the this early period of his life, amid his apprenticeship and his return to Nuremberg in 1494, Dürer’s art exhibits his extravagant expertise with line and his astute attention to detail.

Due to a prearranged marriage, Dürer had to return to Nuremberg. On July 7, 1494, he married Agnes Frey, the daughter of a wealthy local burgher. Agnes and Albrecht appeared completely unsuited for each other; consequently, only months after their wedding, Dürer left for his first trip to Italy, accompanied by friends. While in Italy, he visited his good friend Willibald Pirckheimer; in fact, it was Willibald who introduced Albrecht to classical writings and humanist beliefs. It is believed, perhaps, that Dürer met Jacopo dé Barbari, whose geometrically constructed figures motivated Dürer to contemplate the dimensions of the human body. Also, during his yearlong stay in Venice he completed illustrations of mysterious animals and figures, as well as contemplating nature. During his stay in Italy Albrecht produced some magnificently detailed watercolor landscape studies, presumably during his return journey — for example, a view of the Castle at Trent (1495, National Gallery, London).

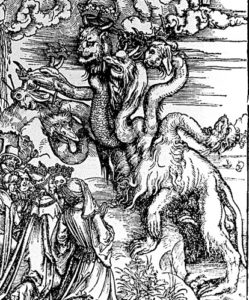

During the ensuing ten years in Nuremberg, from the summer 1495 to fall of 1505, Dürer generated a great abundance of works that  strongly secured his notoriety. (The Apocalypse (1498), a series 15 large, full-page woodcut drawings and the engravings Fall of Man (1504)and Large Fortune (1501-1502)). On the whole, these works and others of the period demonstrate his advancing technical expertise of the woodcut and engraving media. They also demonstrate his awareness of human proportions based on passages by the ancient Roman writer Vitruvius, and reflect his dazzling ingenuity to combine the details of nature into believable illustrations of reality. His Self-Portrait of 1500 (Alte Pinakothek, Munich), in which he illustrated himself as a Christ-like figure, reiterates in visual form his lifelong preoccupation with the elevation of the artist’s status surpassing that of a mere artisan.

strongly secured his notoriety. (The Apocalypse (1498), a series 15 large, full-page woodcut drawings and the engravings Fall of Man (1504)and Large Fortune (1501-1502)). On the whole, these works and others of the period demonstrate his advancing technical expertise of the woodcut and engraving media. They also demonstrate his awareness of human proportions based on passages by the ancient Roman writer Vitruvius, and reflect his dazzling ingenuity to combine the details of nature into believable illustrations of reality. His Self-Portrait of 1500 (Alte Pinakothek, Munich), in which he illustrated himself as a Christ-like figure, reiterates in visual form his lifelong preoccupation with the elevation of the artist’s status surpassing that of a mere artisan.

Albrecht left for Italy in fall 1505 after completing Crowned Death on a Thin Horse (British Museum, London). The plague epidemic in Nuremberg is quite possibly the reason Dürer left for Venice. From 1505 to 1507 he remained in Venice where he met the great master Giovanni Bellini and other artists. During his stay he secured a significant commission for a painting, the Feast of the Rose Garlands (1506, National Museum, Prague), for the German Merchants’ Foundation. Albrecht Dürer also composed the following three paintings in which there is a new gentleness of color and tonal harmony: Christ Among the Doctors (1506, Thyssen Collection, Lugano), Portrait of a Young Woman (1506-1507, Deutsches Museum, Berlin), and lastly Virgin with the Siskin (1506, Deutsches Museum, Berlin).

Upon returning to Nuremberg in February 1507, Dürer began a second period of great productivity. During this time he completed such works as: an Adoration of the Trinity panel, an altarpiece for the Dominican church in Frankfurt (1508-1509, destroyed by fire in 1729), portraits; many prints, two editions of the Passion, woodcuts for the Triumphal Arch for Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, and a series of engravings that included The Knight, Death, and the Devil (1513), Saint Jerome in His Study (1514), and Melancholia I (1514). Through the linear process of engraving, Dürer was able to produce tones of varying darkness and he used them to illustrate a three-dimensional appearance.

In 1520 Dürer learned that Charles V, Maximilian’s successor, was scheduled to be making a voyage to Aachen from Spain. Upon arrival in Aachen, Charles V was crowned Holy Roman emperor of the Habsburg dynasty. Albrecht Dürer had received a yearly stipend from Maximilian for such works as Triumphal Arch (1515-1517), an enormous woodcut measuring 11½ feet by 9¾ feet and other works of art. Albrecht was eager to meet with Charles to have his salary continued. Armed with prints and other artworks, which he sold along the way to finance his trip, Dürer journeyed to Aachen and on to the Lowlands between 1520 and 1521. His audience with Charles proved successful. Albrecht kept a silverpoint diary that consisted of sketches of the many people and places he visited on his pilgrimage to the Netherlands, the first of its kind in the history of art.

He returned to Nuremberg in July 1521, at which time he started to compose portrait engravings. The first, Cardinal Albrecht of  Brandenbergwhich, was completed in 1523. The second, was a portrait engraving of an old friend, Willibald Pirckheimer (1524), and the last of his portrait engravings’ was Erasmus of Rotterdam (1526) are all remindful of the Flemish portrayals of St. Jerome. His last monumental works are two large panels depicting the Four Apostles (1526?, Alte Pinakothek), were presented originally as his gift to the city of Nuremberg. Albrecht Dürer also wrote disquisition’s on perspective (1525, Underweysung der Messung…), on fortification of towns (1527, Etliche Underricht zu Befestigung der Stett…) and lastly on human proportion (1528, incomplete, Vier Bücher von menschlicher Proprtion). On April 6, 1528 Albrecht Dürer died, but shall never be forgotten.

Brandenbergwhich, was completed in 1523. The second, was a portrait engraving of an old friend, Willibald Pirckheimer (1524), and the last of his portrait engravings’ was Erasmus of Rotterdam (1526) are all remindful of the Flemish portrayals of St. Jerome. His last monumental works are two large panels depicting the Four Apostles (1526?, Alte Pinakothek), were presented originally as his gift to the city of Nuremberg. Albrecht Dürer also wrote disquisition’s on perspective (1525, Underweysung der Messung…), on fortification of towns (1527, Etliche Underricht zu Befestigung der Stett…) and lastly on human proportion (1528, incomplete, Vier Bücher von menschlicher Proprtion). On April 6, 1528 Albrecht Dürer died, but shall never be forgotten.

The quality of Dürer’s work, his astonishing output, and his influence on his contemporaries all underscore the significance of his place in the history of art. In a broader context, his curiosity in geometry and mathematical proportions, his keen sense of history, his observances of nature, and his awareness of his own individual potential demonstrate the intellectually inquiring spirit of the Renaissance.

Albercht Durer was one of the greatest painters of his era!