The octagonal building plan was earlier mentioned in the discussion of the baptisteries as a tribute to the ‘double’ four-fold way (Ch. 2.4). The sacrament with the water, in a modern interpretation seen as an initiation into the Fourth Quadrant, can be placed in a wider symbolic context, giving the octagonal design a message on its own.

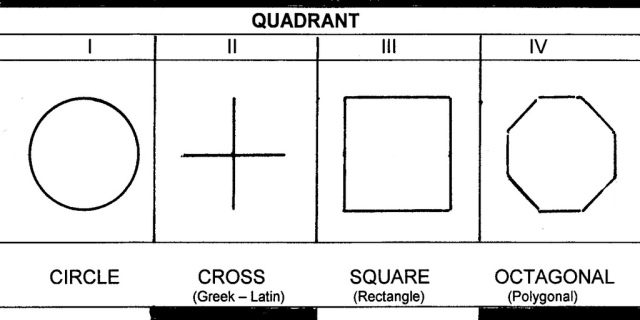

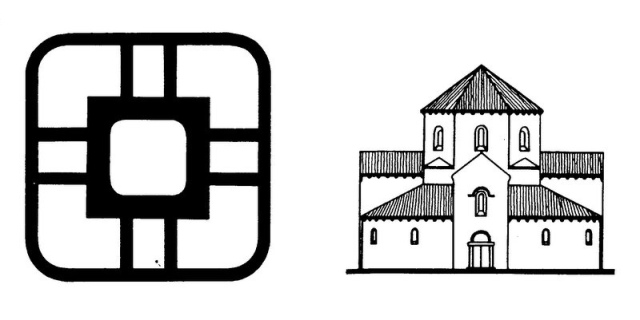

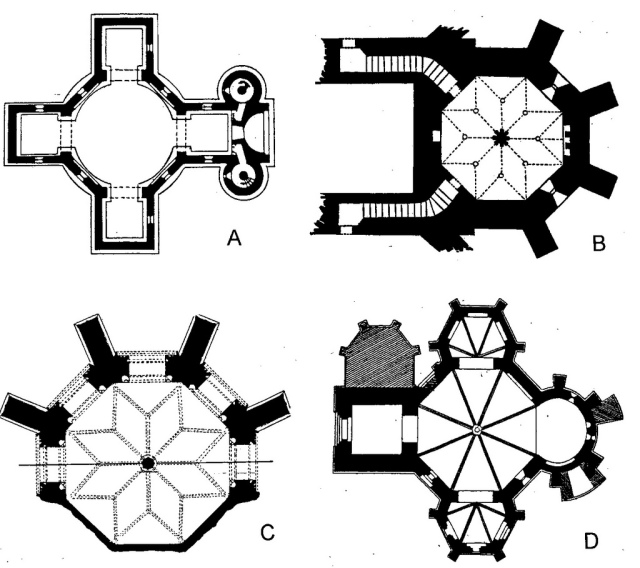

The ‘evolution’ of the ground plan from a circular outlay (I) to the cross (II) and the square (III) finds its apotheosis in the octagonal and polygonal features of the ground plan (IV). Subsequently, the (quadralectic) circle is round again when the polygonal scheme merges with the circle, in a new First Quadrant (fig. 242).

Fig. 242 – This schematic representation of the different types of geometry of the ground plan gives a relation with the quadrants as specific forms of visibility. The general expressions of Unity (I), Separation (II), Partition (III) and Pluriformity (IV) can be seen as psychological units in the interpretation of form.

The geometrical figure can get a psychological value in the communication between the observer and the observed (the building). Each ground plan in this classification represents, in a quadralectic environment, the ‘meaning’ of a particular quadrant in terms of visibility.

- The First Quadrant (I), with its invisible invisibility, is best expressed in the circle, having no beginning and end and no indication of a division. The circular is a movement leading to the unity of itself.

- The development of the invisible visibility in the Second Quadrant (II) can be expressed in the cross, opening the unlimited field in four areas (separation). This division leaves the infinite field still open.

- The unlimited areas are closed in the Third Quadrant (III), when the initial cross is ‘doubled’. A (sub)area is transferred to a part when it is delimited by a set of two parallel lines (see fig. 184). The square (and rectangle) are the graphic representations of this stage of limitation. The part represents the visible visibility and gives the communication its empirical base.

- Finally, the Fourth Quadrant (IV) ‘suffers’ from an abundance of visibility (the visible invisibility). This stage finds its graphic distinction in the multi-division of the four-fold: the octagonal (and polygonal).

The central type of architecture was employed at first by the Church solely as memorial edifices to enclose the tomb of a saint (DAVIES, 1952). The cult of the martyrs, which was particular strong in the eastern part of the dwindling Roman Empire, resulted in the building of tomb-like edifices. These buildings were also used for regular celebration of the liturgy and architects were faced with the problem to enlarge the space in order to accommodate a greater number of people than in the original martyrium. Solutions were found in ambulatories, apses, and/or columns.

Constantine the Great, who won his victory over Maxentius in 312 AD, favored the Christian belief and started to build churches, wherever he could. Literary sources (Eusebius) mentioned the church in Nicomedia, the octagon of Constantine in Antioch (also known as the Golden Church), Jerusalem and other parts of Palestine.

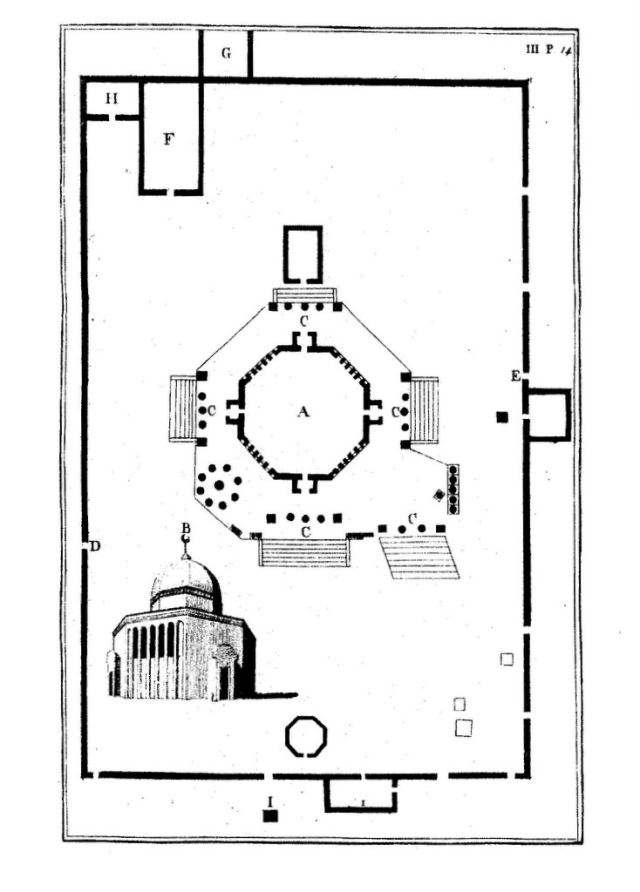

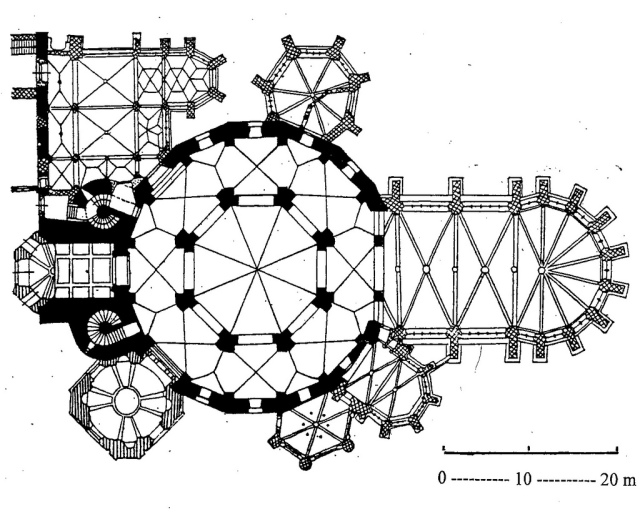

Fig. 243 – The cathedral of Bosra (Syria) is an example of the octagonal design, which was used to express a symbolic reference to a double four-division, associated with the Roman bathes (the caldarium), the (fourth) element of water and eventually to a higher form of division thinking. The church dated from 512 AD.

The boost of the young Christian belief in the form of churches and chapels mend a first necessity to find a type of architectural symbolism, which was appropriate for the revolutionary creed preaching love and peace. It seems more than natural that the new language of Christian understanding was found in the Fourth Quadrant mentality of the Roman Empire.

This ‘Fourth Quadrant’ setting had a keen interest in the ‘last stage’ of the quadralectic development of ground plans: the octagonal. The cathedral of Bosra (Syria) is an archetypal specimen of such a church, which is closely related to the design of the caldarium in the Roman bath (fig. 243). The geometric (octagonal and hexagonal) ground plan of the caldarium, with its symbolism of water and washing, is carried forward as a basic theme of the early churches in Syria.

The city of Bosra is situated some hundred and forty kilometers south of the Syrian capital Damascus on the Hauran plain. The very old city, mentioned in hieroglyph texts dating back to Thutmosis III and Aknaton in the fourteenth century BC, became the major city in the Nabatean kingdom (fourth century BC). The Nabateans were the creators of the spectacular rock city of Petra in Jordan. The Romans took control over the countries of Near East in the first century AD and Arabia was established as a province. Bosra became the new capital at the expense of Petra. Bosra is most famous for its Roman amphitheater (fig. 328), which was later converted into a fortress by the Ayyubids.

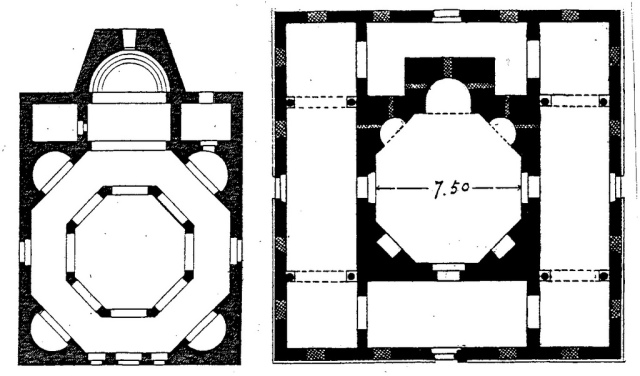

Other buildings in Syria with an octagonal ground plan are the Church of St. George at Ezra’a (or Zor’a), the ancient Zorava (fig. 244 left). This church was built in AD 515 and found its inspiration in a Byzantine martyrium. The small baptistery of Kal’at Simean (fig. 244 right) was part of a much larger complex, consisting of a cross-shaped church built around an octagonal court with the pillar of St. Simeon in the middle (see also fig. 187 – 188). The connection of churches with an octagonal design – with the baptistery (birth) on one side and its function as a martyrium (death) on the other side – could point to an intrinsic aspiration of a ‘Fourth Quadrant’ mind to cross boundaries and explore the area on the other side of the divide.

Fig. 244 – The ground plan of two chapels in Syria, based on the octagonal design. Left: The Church of St George at Zorah (Southern Syria), dating from 515 AD. Right: The baptistery of Kal’at Simean in the convent complex of St. Simeon Stylites.

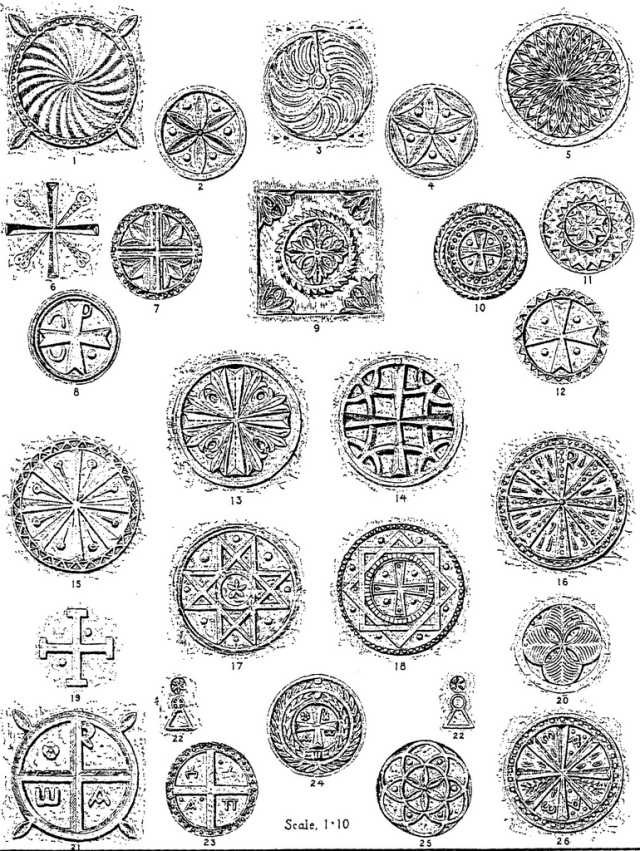

A general attention to the four-fold is found in many early Christian churches in Syria. Baldwin SMITH (1929) gave some examples of round decoration in various churches (fig. 245).

Fig. 245 – Various round decorations in early Christian churches in Syria indicate a strong preference for tetradic geometrical forms.

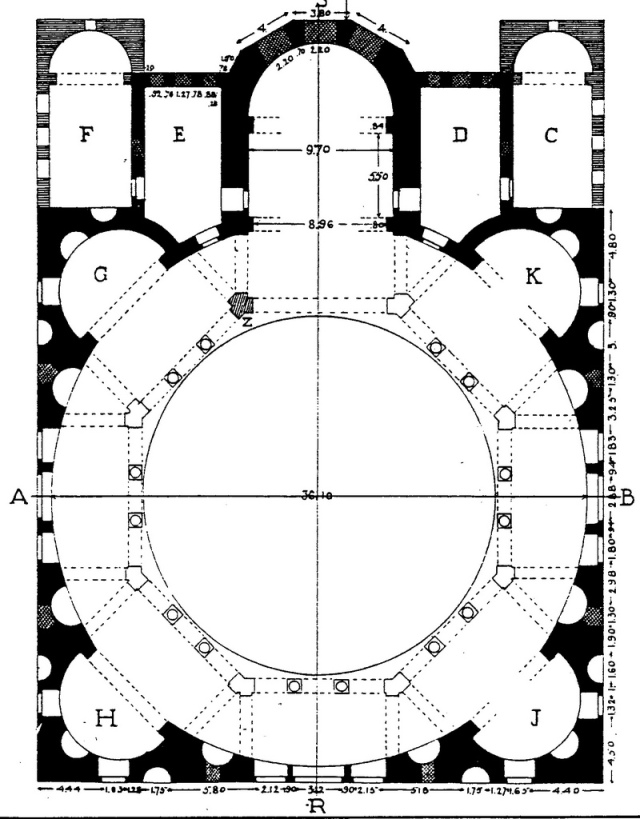

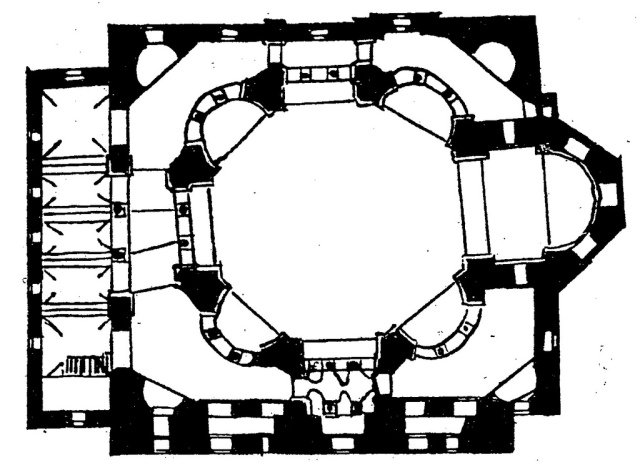

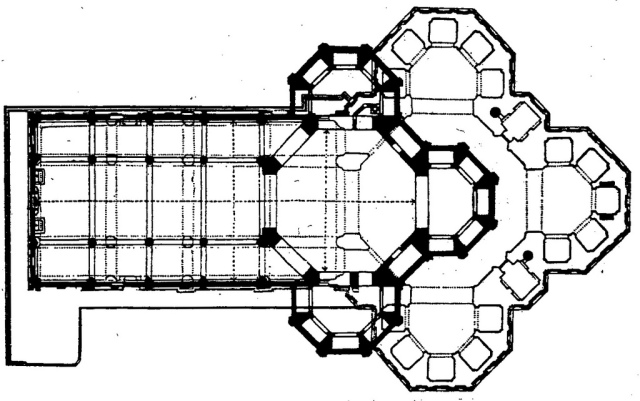

The Church of SS Sergius and Bacchus in Constantinople was founded by Justinian, probably in 527 AD. The church became known as ‘Little Hagia Sophia’, because the general principals of the building were the same as the Hagia Sophia (fig. 246). The cathedral was converted into a mosque between 1506 and 1512. The ground plan was based on an octagonal (fig. 247). The building established a further move of this type of plan from Syria and Palestine to the west (Ravenna). The Christian architecture in Western Europe was ready to pick up the octagonal as a sign of the multitude.

The cathedral of SS Sergius, Bacchus and Leontius is a landmark of ecclesiastical architecture in Constantinople. It was built around AD 528, shortly before the Hagia Sophia (fig. 246). Emperor Justinian made a vow to build a church in 512 AD, when he was condemned to death for taking part in a conspiracy during the reign of his predecessor Anastasias. The martyrs Sergius and Bacchus appeared in a dream to Anastasias on the eve of the execution day and bade him to spare Justinian’s life.

Fig. 246 – The church of SS Sergius, Bacchus and Leontius was part of the Monastery of Hormisdas. Emperor Justinian once lived here in the early sixth century. This avid builder of churches also built the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople and San Vitale in Ravenna.

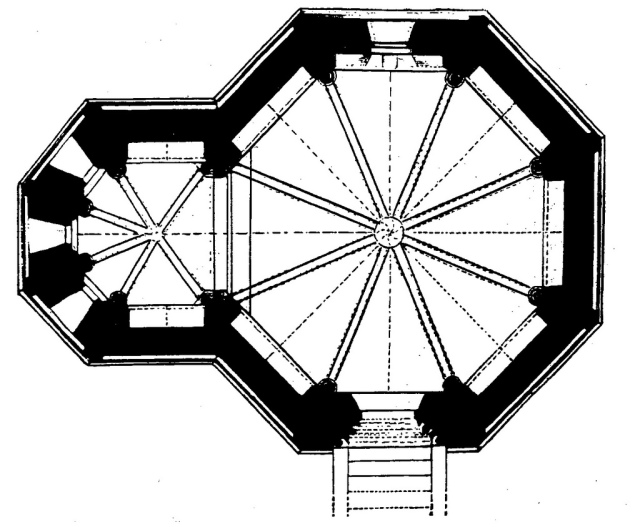

The Saints Sergius and Bacchus Church or Küçuk Aya Sofya (Little Hagia Sophia) is situated near the Palace of Justinian on the Sea of Marmora. The circular building had an octagonal interior colonnade (fig. 247). The columns were made of colored marble, just like the paneling of the walls. The golden mosaic decoration contributed to its character as one of the richest churches in Constantinople. The shallow dome rests, without pendentives, on an octagonal central part. There was an apse to the east and a vestibule to the west, together forming a near square. The church became a mosque in 1509 under Beyazid II, who was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1481 to 1512. The apse of the Huseyin Aga Mosque, as it was now called, was destroyed by the Turks and the frescoes and mosaics on the walls were whitewashed.

The destruction of churches and/or its conversion into mosques continued through the ages and many Christian architectural highlights vanished. The Church of the Holy Apostles has already been mentioned. The Constantine of Lips monastery, with a church dedicated to Saint John the Baptist and a funerary chapel, was converted to the Fenari Isa mosque by sultan Mehmet II in 1453. The mosque was damaged by fire in 1622 and 1917 and remained in ruins after that last date.

The Myrelaion (Holy Anointing Oil) monastery was built by the Greek Emperor Romanus I Lecapenus in 920. The complex was burned down in 1203 as part of the continuous conflicts between Latin (Venetian) traders in Constantinople and the indigenous Greeks. The widening rift between the East and the West culminated during the Fourth Crusade in the sack of Constantinople (April 1204). Hardly ever before did a clash between once-united cultures cause such a devastating effect. The Crusaders spared no one and stole whatever they could. After three days of indiscriminate rape and pillage of houses, palaces and churches the plunder became more systematic and was conducted by the (Latin) government.

The Myrelaion monastery was later converted to the Bodrum Mosque (Bodrum Camii) in 1574 by Sultan Murat III. Further fires in 1784 and 1911 only left the beautiful katholikon (main church) of the complex, with a cross-in-square plan. Underneath the mosque is a cistern with a roof supported by seventy columns of various sizes.

The Jesus Christ Pantocrator monastery complex in Constantinople is also used as a mosque today. The large church was built in 1136 by the Greek Emperor John II Comnenos and designed by the architect Nikephoros. The monastery was looted by the Venetians during the Latin occupation (1204 – 1261) and many icons and holy relics of the Pantocrator were brought to the church of Saint Marco at Venice. The conversion into a mosque (Zeyrek Camii) took place in 1453 (by sultan Mehmet II).

Fig. 247 – The ground plan of the cathedral of SS Sergius, Bacchus and Leontius in Istanbul (Turkey) shows an octagonal inner part within a square.

Many more Christian churches and monasteries in Constantinople (and Turkey in general) felt victim to demolition or were subject to Islamic alterations, including the Hagia Sophia, which is now a museum. Minarets were often added as a specific Islamic tribute to the four-fold.

The Suleyman Mosque in Istanbul, built by the architect Sinan between 1550 and 1557, is an archetypal example of a mosque with four minaret towers. The elongated spires, each with two balconies, are placed at the corners of the arcaded courtyard. The four plump towers added to the Hagia Sophia, on the other end of the square, are an architectural disgrace.

The earliest minarets are found in Egypt as low towers at the four corners of the Mosque of Amir in Cairo (673 AD). A further development is the octagonal minarets of two other mosques in Cairo, the El-Azhar and Kait-bey, dating from the fifteenth century.

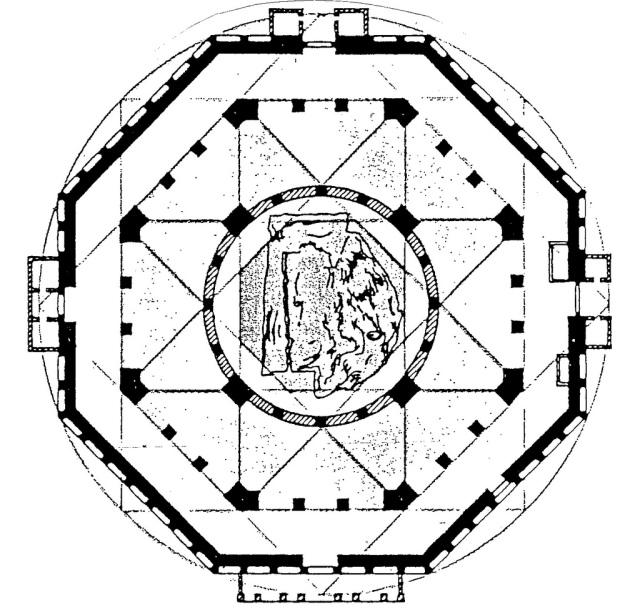

The building of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem begun in 684 AD, some hundred and fifty years after the octagonal scheme was generally introduced in the Near and Middle East (fig. 248). The structure is now the third most important place of worship for the Muslims, after Mecca and Medina. The octagonal outlay of the Dome of the Rock is, in fact, a-representative for a mosque and differs from the more typical examples like the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus (dating from the eighth century). The function of a mosque is a place for the community to pray, with the worshipers in a row facing the east (to Mecca). A rectangular plan with the qibla wall is the most appropriate to mark the direction.

Fig. 248 – The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem is an example of a religious building with an octagonal ground plan. The construction begun in 684 and rebuilding took place in the eleventh century. The dome was placed over as-Sakhra (the rock), on the (supposed) geographical position where the prophet Mohammed ended his Night Journey to Jerusalem and ascended to heaven (Photo: Marten Kuilman, 1984).

Plan of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem by Richard Pococke, 1743 – 1745. PL. 1 in: CRINSON, Mark (1996). Empire Building. Orientalism and Victorian Architecture. Routledge, New York and New York. ISBN 0-415-13940-6

The octagonal design got its first representative in Europe some hundred-and-forty years earlier in the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna. Building started under Archbishop Ecclesius (521 – 534) and finished in 547 (fig. 249). The city of Ravenna, situated on the eastern shore of Italy, was conquered in 540 by Belisarius, a general of Emperor Justinian. Many artisans from Constantinople may have followed the army. They contributed to Ravenna’s works of art, in particular the mosaics.

The Byzantine influence confronted Western Europe at the very moment that the (visible) visibility of the Roman Empire dwindled. The octagonal design – earlier identified as an advanced stage in quadralectic architecture – can be valuated from two sides. A view from the west, makes the octagonal a late expression of a Fourth Quadrant of the Roman cultural period (with a visible stage between 750 BC and 500 AD). The plan of the San Vitale, seen from the east, could also be a young and daring statement of the Byzantine cultural period.The visibility period is for this era tentatively placed between 330 – 1543 AD.

The former situation characterizes the octagonal design as a post-four-fold phenomenon, seen as a ‘decadent’ form of tetradic architecture. The latter option conceives the eight-fold as an experiment in the Second Quadrant. Both options are just as valid. They indicate the difficulties of interpretations of architectural features in general: the position of the observer and the choice in boundaries determines the final classification.

Fig. 249 – The San Vitale Church in Ravenna (Italy) has a double octagonal plan with an inner and outer shell. The diameter of the dome is seventeen meters and its height of thirty meters. The church became, some two hundred and fifty years later in Carolingian times, the prototype of a number of octagonal churches and chapels in Europe (Photo by Marten Kuilman, 1995).

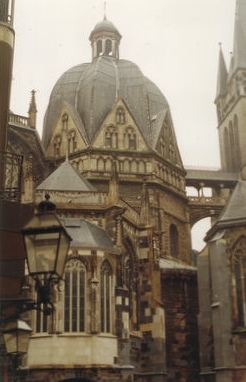

It is of historical significance that a similar situation – with regards to an octagonal design in time – arose between the disappearing Roman Empire and the emerging European cultural period in the middle of the eight century. Charlemagne (742/747 – 814) regarded himself as a ruler over a new Roman Empire. He was crowned by the Pope in Rome in August 800 AD. Charlemagne became acquainted with the achievements of Roman church architecture through his advisers Alcuin, Theodolf, Paul the Deacon, Angilbert, Einhard and others. The ground plan of the San Vitale and its symbolic significance must have attracted his attention, and he ordered to build a similar building in his capital Aachen (Germany) (fig. 250; Photo: Marten Kuil- man, 1992).

It is of historical significance that a similar situation – with regards to an octagonal design in time – arose between the disappearing Roman Empire and the emerging European cultural period in the middle of the eight century. Charlemagne (742/747 – 814) regarded himself as a ruler over a new Roman Empire. He was crowned by the Pope in Rome in August 800 AD. Charlemagne became acquainted with the achievements of Roman church architecture through his advisers Alcuin, Theodolf, Paul the Deacon, Angilbert, Einhard and others. The ground plan of the San Vitale and its symbolic significance must have attracted his attention, and he ordered to build a similar building in his capital Aachen (Germany) (fig. 250; Photo: Marten Kuil- man, 1992).

Fig. 250 – Photo of the exterior (above) and the ground plan (below) of the Münster (Dome church) in Aachen is seen here with various extensions, which were added over the years. The original Carolingian Pfalzkapelle (Palatine chapel), dated from 805 AD, is drawn in black, the Gothic additions are cross-hatched and the Baroque affixture is marked with vertical lines.

The octagonal chapel of Charlemagne was a replica of the San Vitale in Ravenna (547). The San Vitale Church was, in turn, inspired by Byzantine architecture and in particular by the Church of SS Sergius and Bacchus in Constantinople, built around 528.

The octagonal ground plan of the San Vitale Church in Ravenna became a symbolic relay stick. It carried the message of the double-four from an old cultural unit (Roman Empire) to a new one (Europe). The eight-fold in architecture is situated in the uncharted area between the Fourth Quadrant of one (cultural) cycle and the Second Quadrant of the next one.

The sixth and seventh centuries were a time of special interest for the four-fold way of thinking. Europe-as-a-cultural-unit was still in the invisibility stage, before the actual visible visibility of Europe was established in 750 AD. This ‘invisibility’ did not mean that nothing happened or no visibility was produced in any sense. It was just a time of undefined division thinking and the lack of a cultural cadre. No formal decision on the number of division was taken and all options – as far as division thinking was concerned – were open.

The awareness of the four-fold must have been strong in the ‘Dark Ages’ of the European cultural history, without being explicitly noted. People constructed churches and holy places in the firm belief of a God in many disguises and resulted in some remarkable tetragonal buildings, following the lines of the circle, cross, square or octagonal, in one way or another.

The visibility of Carolingian architecture can be seen as an interaction of the tetradic sympathies of the Late Roman Empire and the geometrical spirit of a rejuvenated Celtic Europe. When Europe started to build its own identity, there was still the full width of higher division thinking available to be use in architectural projects.

The chapel in Aachen was copied in various places in Europe (TIMMERS, 1985). The Carolingian church in Torhout (Belgium), started its history in the ninth century as a possible copy of Germigny-des-Prés (fig. 201/202) – with a ground plan of a Greek cross – but might at some stage been covered by an octagonal domed tower (COURTENS, 1969) (fig. 251). This latter suggestion remains a guess, because the outlay of the tower is not reflected in the ground plan and there are no archeological sources to determine the upper part of the oratorium.

Fig. 251 – The Carolingian church in Torhout (Belgium) started in the ninth century with a ground plan of a Greek cross (left), but might have had in a later stage an octagonal tower (right).

The tribulations of history have been particular harsh to this church: it was looted by the Normans in 940, rebuild to become a Roman collegial church, burned down during the religious struggles, rebuild in the seventeenth century, renovated in the eighteenth century, burned down in 1918 during the First World War and burned again in 1940 in the Second World War.

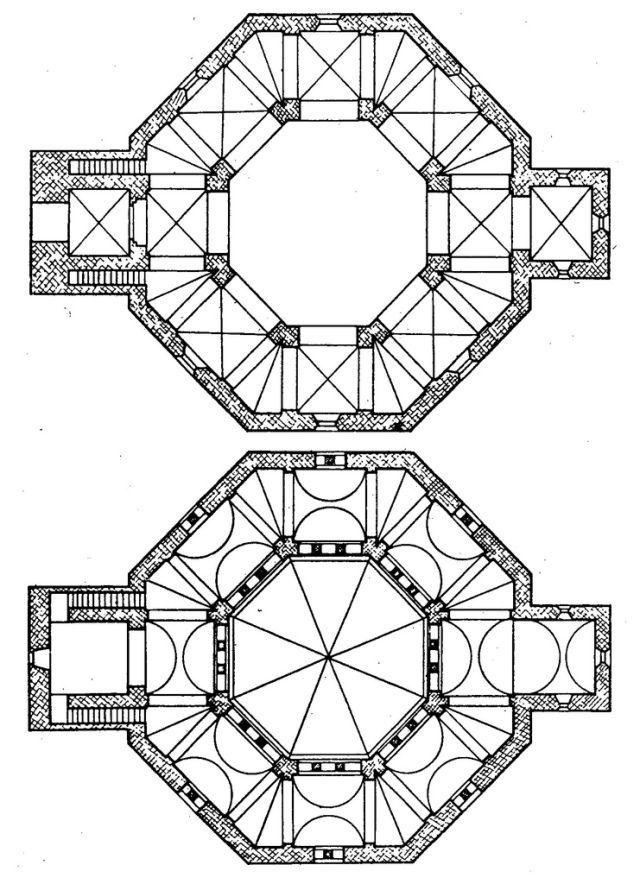

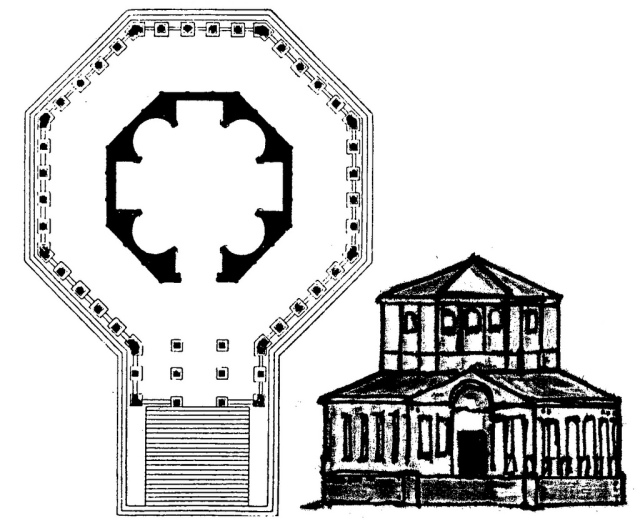

The octagonal plan of the church in Ottmarsheim (Alsace, France), which was already earlier discussed, is inspired by the Palatine chapel in Aachen (fig. 252/253).

Fig. 252 – The building of the octagonal church in Ottmarsheim (Alsace, France) started in 1030 on Merovingian foundations and was consecrated in 1049 by Pope Leo IX (1002 – 1054). The adjoining bell tower was erected in the fifteenth century. The original church – a replica of the Palatine chapel in Aachen – was subsequently demolished in wars and revolutions and restored between 1792 and 1850 (Photo: Marten Kuilman, Jan. 2013).

The religious and symbolic significance of the octagonal – and numerological references in general – was widely understood at the time of construction in the middle of the eleventh century. The work of Dionysius Areopagita (Pseudo-Dionysius) might have been instrumental in this process. This unknown writer was thought to be a pupil of the disciple Paulus and gained his authority. Studies in the late nineteenth century proved that the writings of Dionysius could not antedate 482 AD. The writer is probably Severus of Antioch, who died in 539. The latter was the founder of the trichotomy, proclaiming the three-division as a cosmic principle (WEDEPOHL, 1967).

The manuscripts of Dionysius Aeopagita were given by Emperor Michael (the Stutterer) of Byzantium to Louis the Pius, the son of Charlemagne and translated by abbot Hildum of St. Denis. Twenty-five years later a new translation by John Scotus Eriugena – writer of the ultimate book on the four-division ‘The Division of Nature’ – became the source of studies by Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas (1225 – 1274).

The quintessence of the Corpus Areopagiticum and the writings of John Scotus Eriugena is the relation between the ultimate unity (God) and the world of division (Nature). Pseudo-Dionysius opted, in the sixth century, for the Holy Trinity (three-division) as a guideline, while John Scotus added, in the ninth century, the ‘human’ quaternary (four division) to the spectrum, giving way to the ‘Seven Steps to Heaven’ (3 + 4).

Fig. 253 – The ground floor (upper part) and tribune level (lower part) of the church of Ottmarsheim (Alsace) on the borders of the Rhine, east of Mulhouse, are based on an octagonal design. The church was built in the middle of the eleventh century.

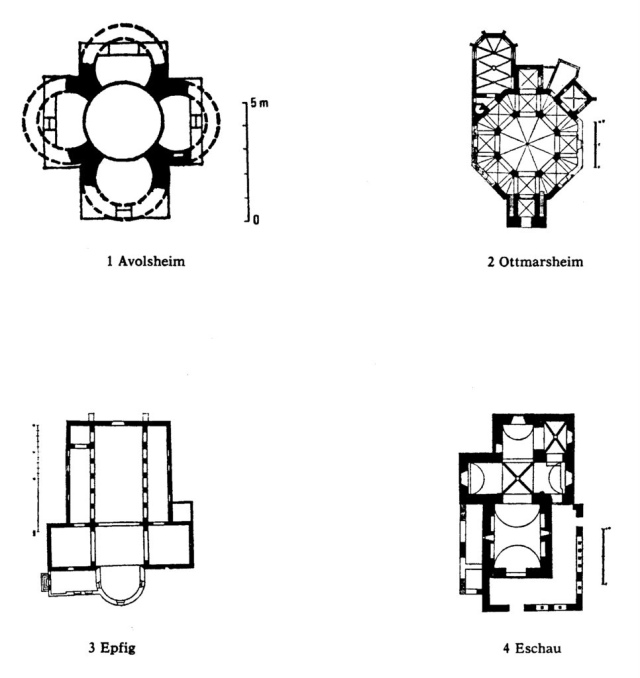

Philippe DOLLINGER (1972) gave several maps of churches in the Alsace, the area on the borderland between south-western Germany and eastern France. Different types of churches with a ground plan based on a tetradic scheme are brought together (fig. 254). They indicate the variety of plans in a limited geographical area. The baptisterium of S. Ulrich (tenth-eleventh century) in Avolsheim (a) uses a strict tetradic scheme consisting of four circles. The original design was shortened in 1773 to follow the lines of a Greek cross. The before-mentioned Church of Ottmarsheim applies the octagonal scheme (b). The church in Epfig (c) is of the basilica type, with the Latin cross in its ground plan as a guideline. The Benedict church in Eschau (d) was founded in 770 by Remigius, bishop of Strasbourg and is one of the oldest churches of Alsace. The church was dedicated to St. Trophine. The bones of St Sophie and her daughters were carried from Rome to Eschau on the 10th of May 777. The place was situated on the important medieval route between Strasbourg and Basel/Augst. A hospital ‘pour pélerins de toutes parts venant’ (for pilgrims of all parts of the world) was built along the strata roman by abbess Chunegundis in 1143.

Fig. 254 – The ground plans of churches in the Alsace (France) indicate different types of geometries: a) Avolsheim; b) Ottmarsheim; c) Epfig and d) Eschau (after DOLLINGER, 1972).

The influence of the octagonal chapel in Aachen seemed fade in the later ninth century or was restricted to the western part of the divided Carolingian empire (VERBEEK, 1967). The palast church of St. Donatien in Bruges (Belgium) is a late copy, built in the twelfth century ‘naer den Aecsen gewerke’ (shaped after Aachen). The Renovatio Imperii Caroli Magni, which can be qualified as an early ‘Renaissance’, lost momentum after the death of Charlemagne and other cultural forces fought for recognition.

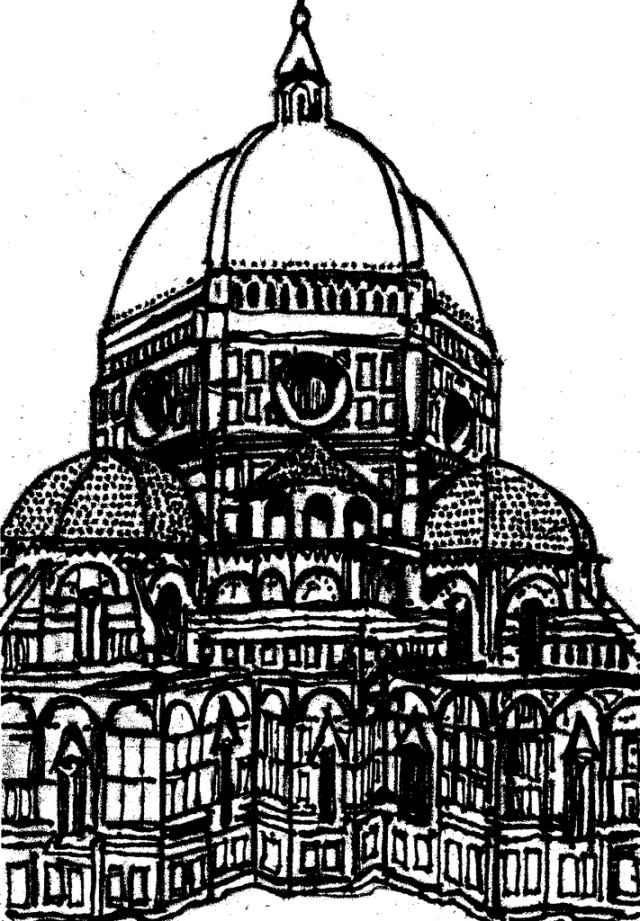

The S. Maria degli Fiore, better known as the Cathedral of Florence (Italy), is an impressive representation of the octagonal identity. It combines the ground plan of the baptistery with the Renaissance geometrical spirit. The San Vitale of Ravenna and the various baptisteries in Italy (see fig. 46) – including the Baptistery of Florence, of which the first plan dated from the middle eleventh century – carried the symbolism of the eightfold forward through the ages to find a new meaning of beauty in the Duomo in Florence (fig. 255).

Fig. 255 – The cupola and octagonal reflections in its ground plan of the Duomo of Florence is a continuation of eight-fold symbolism – associated with water and redemption – as it can be traced back to the architecture of the Roman bath and in the Christian baptisterium (baptistery) (Drawing and photo by Marten Kuilman, 2006).

The history of the cathedral started between the fourth and fifth century when the city of Florence enjoyed a period of wealth. The new church was called Santa Reparata after her miraculous apparition on the anniversary of her martyrdom. Sancta Reparata was born in the third century in Caesarea (Palestine). The story of her life was rather pitiable. She was tortured as a child of eleven years during the persecution of the Christians by Emperor Decius (249/251 AD). She was thrown in the fire, but escaped unharmed. Later she was offered to apostatize, refused and was beheaded.

The original cathedral was demolished after the Gothic-Byzantine war of the sixth century. A rebuilding of the second Santa Reparata took place in the eight of the ninth century, following the original dimensions with three naves, but with the addition of two side chapels in the area of the apse. Arnolfo di Cambio again enlarged its size in a plan in 1294 and the first stone was ceremoniously laid on the eight of September 1296. The ground plan followed the classical outlay of a basilica with a trefoil shaped tribune on which the cupola rests. The cupola aimed at a diameter of forty-five meters.

The work halted for some forty years after the death of Arnolfo di Cambio, but gained momentum after the body of St. Zanobius – buried underneath the Santa Reparata – was found in 1330. The painter and architect Giotto di Bondone (c. 1267 – 1337) became the overseer of the site. The city of Florence had given this famous painter of the frescoes of the Life of St Franciscus in Assisi and in the Arena Chapel in Padua the honorary title of Magnus Magister (Great Master) in 1234. He concentrated his architectural efforts in the three years before his death (in 1337) on the bell tower (Campanile), which is a masterpiece in his own right.

Fig. 256 – The original plan of the church of S. Maria degli Fiori (Duomo) in Florence by Arnolfo di Cambio (1293) was enlarged by Francesco Talenti in the middle of the fourteenth century. The construction of the cupola was the work of Filippo Brunelleschi (1377 – 1446). Pope Eugene IV consecrated the church in 1436, hundred and forty years after the first stone was laid. Additions, like the mounting of the lantern (in 1461) and the covering of the external walls by marble (in the late nineteenth century, 1886) had to wait until even later.

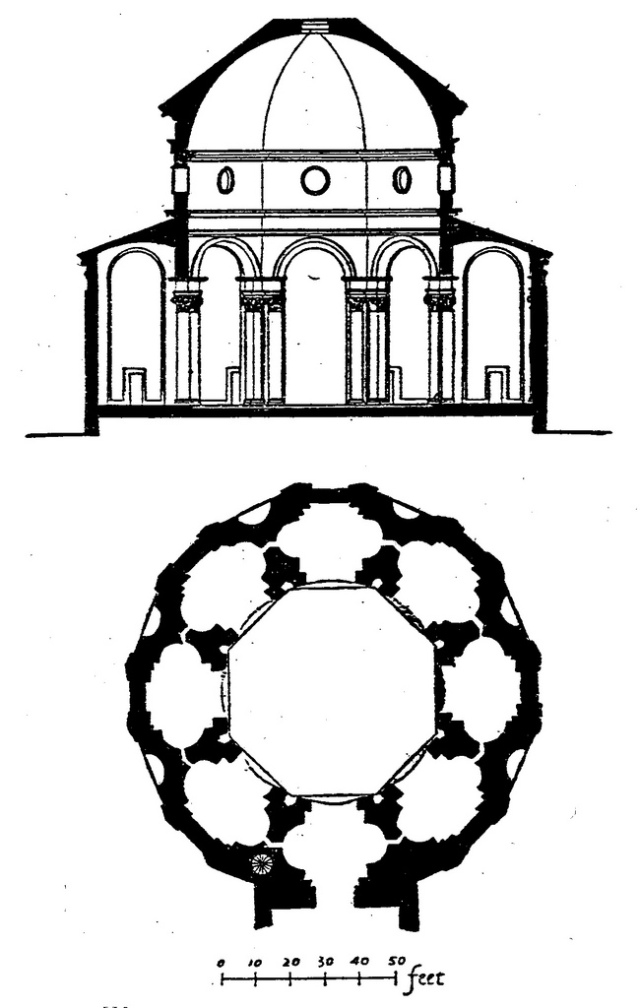

Francesco Talenti became the new overseer between 1349 and 1359. He completed the bell tower and enlarged the original design of the Santa Reparata (fig. 256). The final execution of the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral was the work of Filippo Brunelleschi (1377 – 1446). Brunelleschi was a goldsmith by training, but had a special interest in construction problems. The octagonal dome of the cathedral of Florence posed a par-ticular challenge. He believed that the Baptistery was a Roman building, worthy of imitation. The dome started in 1417 and building kept going on for twenty years. Brunelleschi worked in the meantime on the plan of the Rotonda of Santa Maria degli Angeli, also in Florence. The building started around 1434, but was not finished during Brunelleschi´s lifetime (fig. 257).

Fig. 257 – The Church of S. Maria degli Angeli in Florence was designed by Filippo Brunelleschi around 1434. The round building had an octagonal inner plan – and marked in its design a direct line from the early Renaissance to the circular buildings of antiquity.

The octagonal design in Germany, as established in the Carolingian Pfalz Kapelle in Aachen (in the early ninth century), was an architectonic statement in his own right, but had few direct followers. There were, on the other hand, remarkable predecessors, other than the traditional reference to the San Vitale Church in Ravenna: the Gallo-Roman Umgangstempel (see also fig. 168). The distribution of these temples in Central Europe is given in fig. 101.

An octagonal example is situated geographically some hundred and eighty kilometers to the south east of Aachen and can be found in the city of Mainz. The reconstruction of the building in Mainz is shown in fig. 258 and was measured by E. Schmidt, Stuttgart. The pagan temple was probably in use by the First Legion (Legio I Asiuatrix), which was stationed along the river Rhine in the first century AD.

Fig. 258 – This octagonal temple in Mainz was part of a whole string of similar (pagan) temples throughout Roman Western Europe, dating from the last part of the first century AD to the beginning of the second century. The temple had a double wall and could be either round, square of octagonal. These temples might have influenced Emperor Charlemagne – some sixth centuries later – to build his Aachen chapel in just the same way.

The mausoleum of Emperor Diocletian in Split (Spalato) also followed the octagonal tradition of the Umgangstempel (see also fig. 7). The imperial complex was built in the fourth century, by builders, who were fully aware of the role of symbolism in architecture.

The eightfold chapel in the Valkhof in Nijmegen (Nederland) – misleadingly be called the Carolingian chapel – is dated from around 1030. This beautiful situated sanctuary on the banks of the Waal River was probably initiated by Conrad II, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. He reigned from ca 990 – 1039 and gave a boost to the German-European identity.

The Valkhof in Nijmegen (Nederland) – Photo: Marten Kuilman (2010).

The octagonal design picked up momentum in the twelfth century at several places throughout Germany. The Busdorf Church at Paderborn (Nordrhein-Westfalen) was part of a Romanesque cloister. The main building phases were in the eleventh, twelfth and seventeenth century. The ground plan is a combination of a Greek cross, the circular and the octagonal – making it an ideal piece of quadralectic architecture (fig. 259A).

Fig. 259 – A number of churches with an octagonal ground plan in Germany. A. The ground plan of the Busdorf Church in Paderborn (Nordrhein-Westfalen); B. The octagonal crypt of the Stephans Church in Kourim, Bohemen; C. The S. Aegidius Church in Oschatz (Saxony); D. The (former) SS Maria and Laurentius Church in Ludorf (Mecklenburg).

The crypt of the Stephansdom in Kourim (Bohemia) was part of a religious complex built by the Cistercians Order (fig. 259B). The Roman/Gothic church was of the basilica type, with large towers on its side. The crypt (underground chapel), called Katerinka, has an octagonal plan. The theme is reflected in the ribs of the roof as an eighth pointed star. This form of a roof might be the oldest of this type on the Continent (outside England).

The S. Aegidius Church is the hallmark of the small town of Oschatz in Saxony with two spires of seventy-five meters. The church started as a chapel of wooden church in the eleventh century. The first stone church dated from the fourteenth century, but was demolished by the Hussites (a militant Protestant group under the leadership of the religious reformer Johannes Huss) in 1429.

The rebuilding took place from 1443 onwards and was in Gothic style. The crypt underneath the altar choir took shape in 1464, following an octagonal design (fig. 259C). The S. Aegius Church changed to an Evangelical-Lutherian denomination (in 1539) with the introduction of the Reformation. Further fires in 1616 and 1842 damaged the church and the present building is the result of renovations between 1846 and 1849.

The Maria and Laurentius Church in Ludorf in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern follows the central scheme (fig. 259D/260). The church was consecrated in 1346, but the building is probably one and a half century older – the oldest part being the eastern apsis and cupola. The idea of the octagonal ground plan could have been brought home from Jerusalem (derived from the Dome of the Rock rather than the round Anastasis of the Holy Sepulchre) by the Crusader Wipert of Morin, and is unique in Northern Germany.

Fig. 260 – The octagonal church of Ludorf (Saxony, Germany) was consecrated in May, 1346. The idea of the ground plan might be introduced by visitors to the Holy Land, who saw the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.

The ‘Karner’ (burial chapel) in Oedenburg is a typical example of similar two-story chapels in Austria (fig. 261). The chapel has strong ties with the mausoleum: the lower part was used as storage room for the bones of the deceased, while the upper part was a place for remembrance. Some hundred and ten ‘Karner’ chapel are known from Southern Germany and Austria, in particular in the provinces Lower Austria and Kärnten (MERBACK, 1994/1995). The Charnel (Beinhaus) in Tulln, situated some forty-two kilometers west of Vienna on the south bank of the Danube, is one of the finest in the country. The polygon building dates from the mid-thirteenth century and is decorated with capitals and arches.

Fig. 261 – This ‘Karner’ or funeral chapel is added to the church in Oedenburg (Lower Austria).

Another good example is the St. Barbara Chapel in Mauthausen (Austria), a small place known from its concentration camp (Konzentrationslager) in the Second World War. The chapel is also from the thirteenth century. The symbolism of the round and the octagonal have been exceptionally treated here. The lower three-quarter of the building is round, while the upper quarter is octagonal, just like the roof. The funerary chapel is part of the parish church of S. Nicholas.

The tower of Charroux, south of Poitiers (France) is an astonishing illustration of the tribulations of a place of worship (SCHWERING-ILLERT, 1963; ECKSTEIN, 1975). Originally, the Celts had lived in the area and left a number of dolmen, autels and tumuli in the area around Charroux. Then the Romans conquered the land and called the place Carrofum. They provided the infrastructure and the place became in Gallo-Roman times an important road crossing. The name of the place reflects this position: carruvium being a low-Latin expression of the word quadrivium (carrefour). The quadrivium became later known as part of the medieval curriculum of the Seven Liberal Arts, pointing to the disciplines of arithmic, geometry, cosmology and music (harmony).

The building of the Abbey Saint-Sauveur started in the eight century, first mainly in wood and later (815) also in stone. The cloister became a resting place on the pilgrimage trail to Santiago de Compostela. However, the Norseman also visited the community when they pillaged the countryside and put fire to properties. The Synod of Charroux in 989 was a meeting of the bishops in the Aquitaine to proclaim the Peace of God. The decrees aimed to outlaw violence against the churches, the poor and clergyman.

The abbatial church was built in the eleventh century, following the Carolingian and Benedictine tradition. The original abbey had a length of some hundred and fourteen meters and offers a unique plan. The building suffered badly in the Hundred Years War and in the Religious Wars. Only three monks lived on the premises in 1790 and the abbey lay in ruins. The rest of the church was used as material for building, finding its way into many houses in the village. Only the Roman ‘tour-latern’ now remains, the so-called ‘Tour Charlemagne’ with a height of forty meters (fig. 262).

Fig. 262 – The octagonal tower of Charroux (Vienne), also known as the ‘Tour Charlemagne’, is the only remains of an old Benedictine abbey, dating of the eleventh century (Photo: Marten Kuilman, 2006).

This small survey of octagonal elements in the history of architecture is only a glimpse in the overwhelming richness of the eight-fold as it was applied in building. A line of analogy can be distinguished from the ground plan of the Roman cold bath (caldarium) to the Gallo-Roman Umgangstempel and the (Christian) baptisteries. The Carolingian spirit of a Holy Roman Empire could easily embrace the presence of the eight-fold in architecture in central Europe, resulting in Charlemagne’s chapel in Aachen.

The design got fresh impulses in the eleventh and twelfth century, when Christian Europe reached for a new material visibility full of temperament. The Renaissance, which started in Italy in the fourteenth century, looked again to the past and blended the double four into its own ideas about beauty. The octagonal and polygonal exponents of geometry (interpreted as Fourth Quadrant characteristics) belong to the last stage before the circular (of the First Quadrant) takes over. In that quality, they have been marker points throughout the ages and are worth studying.

Marten,May I have your permission to use the diagram of the geometric development of the octagonal plan (Fig 242) and also quoting you for my new book that I am writing on housing using the octagon as a basis? My two previous books on interior design are:

http://www.id-sphere.com/2012/09/books-interior-design-theory-and-process/ http://www.springer.com/978-3-319-16473-1

Many thanks.

You can use the geometric development of the octagonal plan and a quote is fine. I just want to point out a broadening in the given development (which is not mentioned in the text here). The circle (I) is associated with the octagonal (IV), but the cross (II) is reflected (later) in the grid (IV). The Fourth Quadrant (IV) contains in due course two different elements of development: one from the circle (octagonal) and another one from the cross (resulting in a grid). This makes an interesting playing field of thoughts in this important part of the communication.

Thank you for a very interesting article. I am writing a book about round churches and your article was very helpful. I am living next to a round church in Tønsberg, Norway. Sadly the church is in ruin. Greetings from Eivind Luthen

Excellent article about the octagonal church architecture. Very informative and lovely to see all the drawings and photos. Very helpful in understanding the architecture of those times.

Thank you Aadil for your comment. Marten

Isn’t there a Cabbalistic element in the choice for an octagonal shape for Churches.

Transsubstantiation in the Eucharist in essence being a magical operation.

The number 8 being connoted with the 8th emanation of the Deity and with magical operations in the same fashion pentagonal structures are associated with military matters as is demonstrated by the Pentagon, the 5th emanation being connoted with the more retributive aspects of the Deity according to Cabbalistic teachings.

I would like to use some of your octagonal ground plans to illustrate my article on the subject on my Medium site.