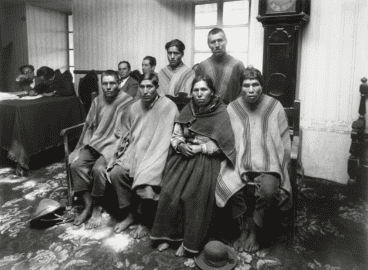

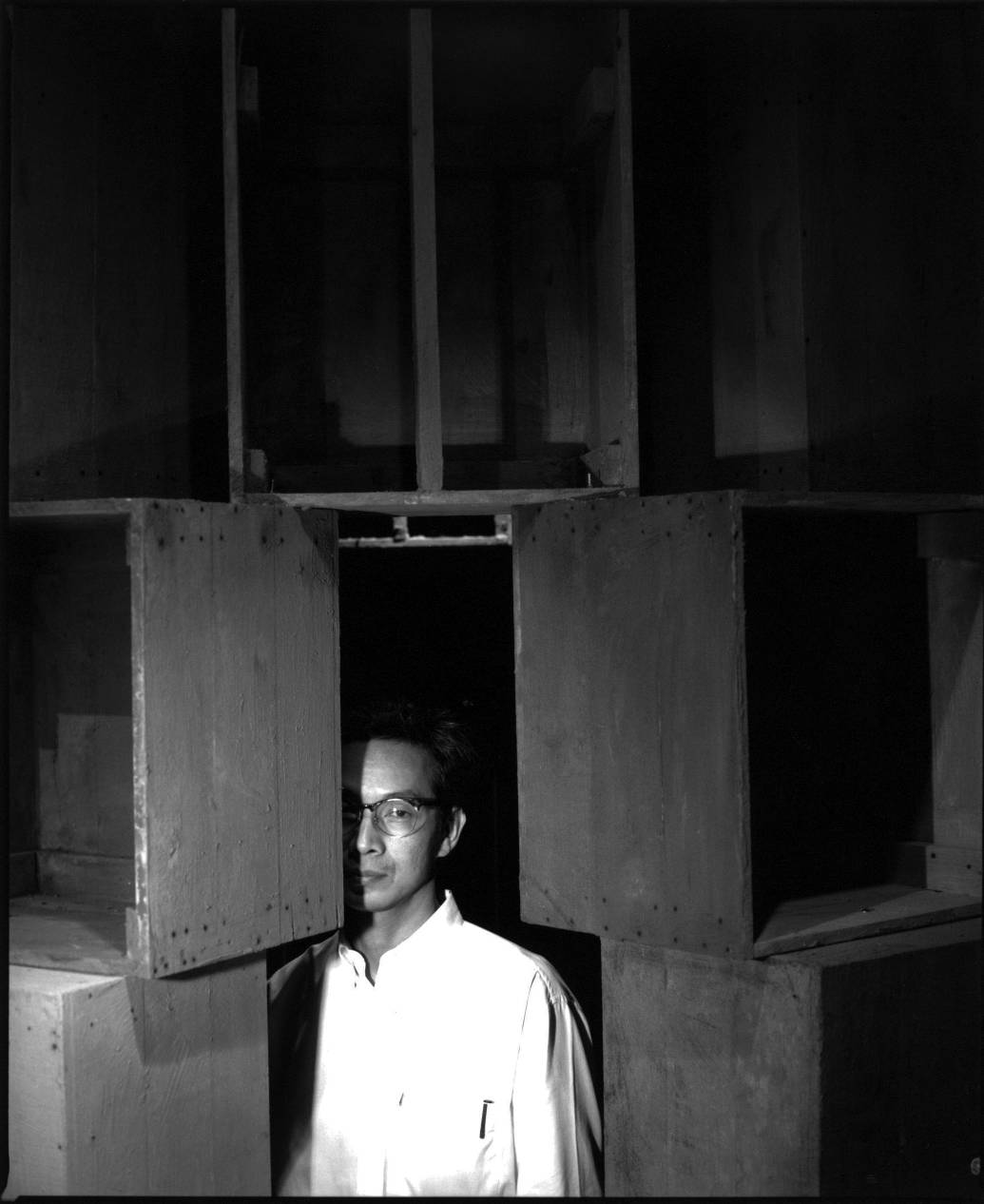

Invocation of Montien Boonma (1953–2000) almost always arrives in the form of an elegy. Best known for meditative sculptural installations that incorporate herbal medicines and earthy fragrances, he was a rising star of the international biennial circuit before an untimely death from cancer at the age of forty-seven. For many curators and critics who came to prominence in the 1990s, Montien’s work carried the promise of profundity for “contemporary Asian art,” back when the field still had to prove its capacity for aesthetic and philosophical complexity in comparison to so-called traditional art.1See, for instance, Apinan Poshyananda, Montien Boonma: Temple of the Mind, exh. cat. (New York: Asia Society, 2003); and Vishakha N. Desai, “Thailand: Montien Boonma,” ArtAsiaPacific 37 (January 2003): 34. His contemplative brand of Buddhism—unbeholden to national essentialisms but also ostensibly undiluted by “sloppy New Age enthusiasms”—exemplified a particularly credible cross-cultural currency.2Mark Stevens, “Belly Up,” New York Magazine, April 24, 2003. In his native Thailand, Montien was likewise heralded as a pathfinder who pioneered an approach to local materials and religious subject matter without nostalgia.3See, for instance, Somporn Rodboon, “Montien Boonma: atalak thongthin su lok sinlapa ruamsamai” [Montien Boonma: From Local Identities to the Contemporary Art World] (lecture, Wat Umong, Chiang Mai, February 25, 2021). His legacy has been consolidated in fetes of hagiographic commemoration otherwise reserved for modernist masters of an older generation.4Major exhibitions in Thailand include Death Before Dying: The Return of Montien Boonma, curated by Apinan Poshyananda, National Gallery of Bangkok, February 17–April 20, 2005; [Montien Boonma]: Unbuilt/Rare Works, curated by Gridthiya Gaweewong and Gregory Galligan, Jim Thompson Art Center, Bangkok, April 11–July 31, 2013; Spiritual Ties: A Tribute to Montien Boonma, curated by Somporn Rodboon, The Art Center, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, July 26–September 7, 2013; and Departed <> Revisited, curated by Navin Rawanchaikul, Wat Umong, Chiang Mai, December 26, 2020–March 28, 2021. Death has, in short, made a heroic figure out of Montien.

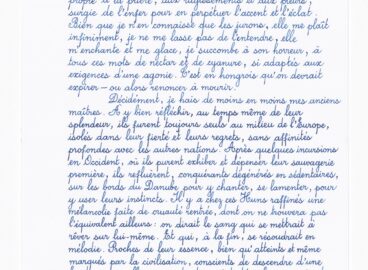

If these narratives deserve revisiting, it is not only for the sobriety of historical distance, but also in light of the rich archive that Montien left behind. Located in his old studio space in Bangkok, Montien Atelier houses a collection of drawings, letters, faxes, and emails that chart the artist’s trajectory across Chiang Mai, Paris, New York, Tokyo, Brisbane, and other nodes of an emergent contemporary art world. More than an index of geographic mobility, the selection of documents catalogued thus far reveals his expansive intellectual appetite, ranging from an engagement with European philosophy (notes on Roland Barthes, Jean Baudrillard, Edmund Husserl, Immanuel Kant, Jean-François Lyotard, and Jean-Paul Sartre abound) to an interest in the vibrant world of religious commerce during the boom years of the Thai economy (think magical amulets and spirit shrines).5As comparative literature scholar Chetana Nagavajara argues: “That he [Montien] was deeply immersed in Buddhism does not require any substantiation. But his interest in Western thinking is worth investigating.” Chetana Nagavajara, “Random Thoughts on Montien Boonma and the Archival Approach to His Life and Work,” Thai Criticism Project, Silpakorn University,July 12, 2013. A less dreamy picture of an artist emerges here, one perhaps as doubting and skeptical as he is faithful, and certainly without the mystique of ascetic withdrawal. The archive offers the possibility of refiguring Montien’s relationship to the sign of Buddhism that hangs over his oeuvre.

Consider House of Hope (1996–97), a work that marks a departure from his usual reference to Buddhist iconography for the generic shape of a gabled house. An installation shot taken at Deitch Projects in New York presents the work as a dramatic stage set against an otherworldly backdrop (fig. 2). We can imagine wandering up the red steps into the porous but forebodingly dense forest of medicinal prayer beads. There is an urge to enter and be absorbed into this shadow architecture, the hanging weight of which centers the gravity of the room. Painted directly onto the walls with aromatic herbal pigments, a band of smoky clouds wafts in an atmosphere that intimates ethereal ascent. “House of Hope is abstract,” Montien noted in 1997. “It concerns the existence of something large, but which we cannot grasp. Like how we think God exists, but we have never truly known. He has never shown himself. It has been a story of hope all along.”6Paisal Teerapongwit, “Baan haeng khwam wang khong Montien Boonma” [Montien Boonma’s House of Hope], Seesan, 1997, 36. All too aware of being pigeonholed as a “Buddhist artist,” Montien gestures here toward a more expansive thematization of faith.

Critic Holland Cotter would later call House of Hope “the most moving New York gallery installation I had seen in years.”7Holland Cotter, “ART REVIEW; Immersed in Buddhism and Its Meditation on Paradoxes,” New York Times, February 21, 2003. Others praised it for offering an emotional experience that transcended specific religious reference, reaching a “doctrine-free spiritualization of art.”8Jonathan Goodman, “Focus: Montien Boonma,” Sculpture 22, no. 7 (September 2003): 20–21. However, with no other work of his did Montien express such profound skepticism. In various published and unpublished conversations, he revealed his unhappiness with its first iteration in Japan, ambivalence about the New York version, and uncertainty if it would restage well in Athens.9See Paisal, “Baan haeng khwam wang khong Montien Boonma,” 37–38; Montien Boonma, unpublished transcript of interview with Paisal Teerapongwit, 1997, Montien Boonma Archives (hereafter MBA); and Montien Boonma, uncatalogued notes, May 22, 1998, MBA. Production and staging issues abounded in what was his grandest project to date, especially if measured by its unprecedented scale of production (over 300,000 beads and 440 stools). Yet Montien’s frustration, I think, concerned more than the challenge of achieving largeness or immersion. His choice of a culturally unspecific shape, staged within the archetypal space of the white cube, was an ambitious experiment with the neutral. In an art world that was quick to collapse aesthetic experience into essentialisms (Thai, Buddhist) and universalisms (spiritual, transcendent), what did it mean to chart a middle path?

But first, a detour through the question of shape. After all, Montien’s oeuvre sees the preponderance of immediately recognizable silhouettes, whether the Buddha’s head and torso, the round vessel of the monk’s alms bowl, or the conical towerlike construction of the stupa (Buddhist reliquary). Exemplary of his earliest work, Paintings and Candles (1990) de-monumentalizes the form of a stupa into a precarious pyramid of wax panels leaning against the wall (fig. 3). Coated with a thick layer of candle wax, the surface is then charred to produce a smoky triangular shadow across the panels. The fleshy skin is molten and gouged with wounding incisions that turn the architectural reference into a carnal one or, according to Montien, “give it a real physical presence in the room at the same level as the viewer.”10Montien Boonma, uncatalogued notes, August 8, 1991, MBA. Where critics were quick to take any reference to the stupa as evidence of his Buddhist faith, they missed altogether the unorthodoxy of his gesture. Paintings and Candles carries a sensuous organicity in a manner that recalls, almost contemporaneously, Janine Antoni’s lard cubes and Wolfgang Laib’s beeswax panels.11These comparisons were not lost on critics in the 1990s. See, for instance, Frances Richard, “Montien Boonma: Deitch Projects,” Artforum 36, no. 6 (February 1998): 91–92. As much as Montien may have been interested in evoking the stupa’s historical ritual and symbolic associations, he rooted the encounter firmly in the present tense of a corporeal encounter. Shape became the basis for a psychosomatic relationship between geometric figure and lived body.12On an expanded modernist genealogy for this inquiry, see David Joselit, Michelle Kuo, and Amy Sillman, “Shape: A Conversation,” October 172 (Spring 2020): 135–46. On an even more expanded genealogy of shape in relation to Buddhist architecture (and as it relates to Montien, the Buddha’s house), see Kazi Ashraf, The Hermit’s Hut: Architecture and Asceticism in India (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2013).

No mere formalist concern, shape cut to the heart of identity politics in the 1990s, when the evocation of objects native to an artist’s background routinely served as a cipher for cultural difference, and often exoticism. Shape, however, also afforded escape from the tyranny of origins. A contemporaneous comparison for House of Hope might be found in Do Ho Suh’s geometrized life-size replicas of his childhood home, whose ethereal apparition in silk gauze suggests the fluid physical mobility of the itinerant artist.13Joan Kee, “Some Thoughts on the Practice of Oscillation: Works by Suh Do-Ho and Oh Inhwan,” Third Text 17, no. 2 (2003): 141–50. For both Suh and Montien, architecture need not be durable or monumental—or preoccupied with cultural memory—to have staying power. But where Suh insisted in the haunting domestic detail of his house’s specific furnishings and finishings, Montien reached for a house in a more elemental sense with his earthy materials and woody scents. Seemingly rootless form, if rendered through evocative materiality, can hold a phantasmatic quality. By playing on this tension between architectural abstraction and an appeal to the deeply visceral, House of Hope holds out a promise of remapping the terms of the specificity and malleability of cultural associations.

Montien’s approach in the work might then be described as less tethered to symbolic meaning and more concerned about the dynamics that intertwine building and body, shape and subjectivity. The house that from afar looks durable and even solid, when up close becomes diffuse, no longer a discrete geometric form that we confront, but rather a blurred field. Its earthy, fragrant materiality conditions the entire interior weather of a space, playing off the currents of swirling clouds that evoke the gentle heat of incense. Montien was known to invite viewers to lay down on the red wooden platform, to be showered in what he called a “torrent of black rain.”14Apisit Nongbua, conversation with the author, May 9, 2023, in which he recalled how Montien referred to the beads. The cool touch of the clay beads cuts against the temperature of the vermilion sky. Minimalism gives way to meteorology, as we oscillate between seeming tactility to synesthetic immateriality and back.15As Montien described the oscillatory experience of House of Hope: “From high to low, from low to high, from large to formless, from enclosed to open. The mural gives the impression of a massive landscape, but it is not massive. It is only superficial, only surface.” Paisal, “Baan haeng khwam wang khong Montien Boonma,” 37. His analogy to religious space provides insight: “When you enter a temple, it makes you warm. I use the word ‘warm’ because there’s the feeling that we will be given help—like having a father and mother to protect us. These shrines used to be centers of healing and faith, where people would go and propitiate the gods and at the same time do chants and take medicine, so it was also a kind of psychotherapy.”16Montien Boonma, “Montien Boonma: Interviewed by Albert Paravi Wongchirachai,” ArtAsiaPacific 2, no. 3 (April 1995): 81. Architecture as constructed form or iconographic order may provide an entry point, but it is the way that space inscribes social relations and shared mood that is of interest. In other words, if shape was Montien’s compositional tool, his true medium was atmospheric. At turns warming and cooling, House of Hope changes the weather in the white cube to one that is less aridly didactic or cerebral, priming mind and body for more supple states of becoming.

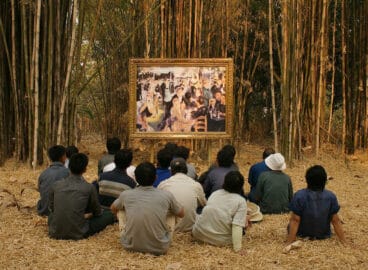

If, so far, we have meandered—between shape and subjectivity, structure and environment, directed attention and diffuse affect—it is for reasons that relate back to the question of Buddhism that hangs over this discussion. Most accounts cite Montien’s debt to both the forest monk Ajarn Chah (1918–1992) and the reformist monk Buddhadasa Bhikkhu (1906–1993), for whom meditation was a central practice. These references provided a dependable source of Montien’s moral and intellectual legitimacy, especially for a Euro-American audience—or even an upper-middle class Thai audience—that favored a soteriology of withdrawn ascetism. And yet, his investment in practices of oscillation points to a structure of experience that barely accords with the focused concentration that is essential to meditation. Even as his works may offer opportunities for detached repose, they also invite interaction and even touch, driving bodily performances that go beyond the purely meditative. The minimalism of Montien’s shapes is a red herring that misleads us down a genealogy of quiet contemplative Buddhism, when his works may in fact have more to do with crowded and colorful everyday scenes of ritual propitiation that appeal directly to the senses.

After all, Montien was more attuned to the consumerist trappings of religion than most. Following his wife’s cancer diagnosis in 1994, he went in search of hope and healing from the many cults that sprung up in the bubble years of the Thai economy. In a 1995 interview, he recalls: “I went and made propitiations at shrines everywhere. I would chant continuously the Jinapanjara (an ancient mantra, popularised by the late Buddhist saint, Somdej Toh of Wat Rakhang) and whatever I found in Lok Thip magazine (literally ‘Heavenly World,’ a journal focused on the Buddhist supernatural). I took an oath to Mother Kuan Im (Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion) to stop eating beef. I went to pray to the Buddha relics of Doi Suthep and Khruba Sriwichai.”17Montien, “Montien Boonma: Interviewed by Albert Paravi Wongchirachai,” 76. Instead of casting Montien as a pensive thinker, it might then be more accurate to also picture him, at times, as a restless pilgrim in search of talismanic promises. The grammar of his Buddhism entailed breathing meditation, but also propitiation rituals, esoteric prayers, and offerings to charismatic images of Hindu, Chinese, and animist bent.18Montien did not care much for the mutual exclusivity of religions either. He recalled in 1995: “When I was abroad, I found worshipping the Holy Mother by candlelight very special; it feels like she’s looking at you. She answered my prayers too.” Boonma, “Montien Boonma: Interviewed by Albert Paravi Wongchirachai,” 79. In these scenarios, atmosphere again matters. “If you go look in Khmer temples [prasat khom], you will see black marks on the walls, traces of incense and candle smoke. It is a reminder of prayer, stained with memories of begging.”19Montien, unpublished transcript of interview with Paisal. For all that religion may offer by way of doctrines and promises of ultimate truth, Montien turned to the primal importance of acknowledging what we do not know. The house of hope is a place of not knowing.

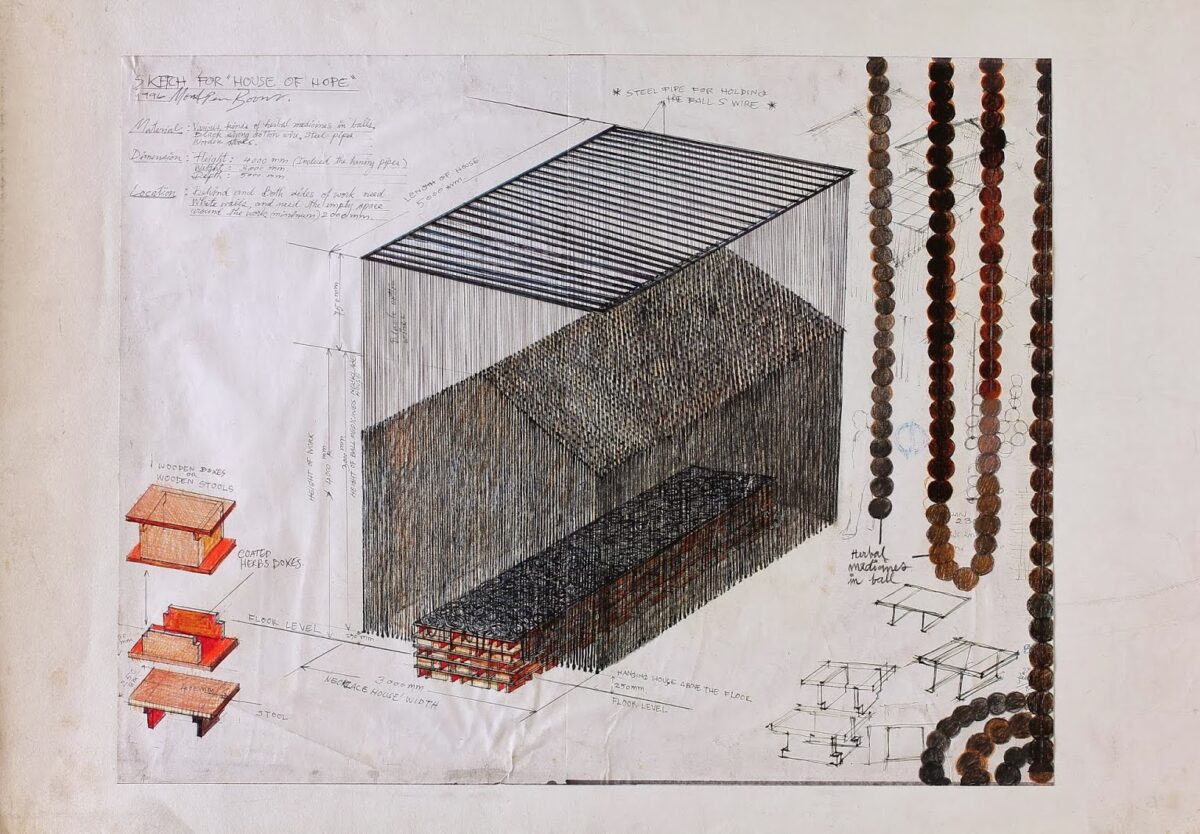

It is under this sign of ambivalence and openness that a less idealistic account of House of Hope’s realizationcomes into view. For the initial idea of the work lacked any of the immersive atmospheric play that we now see as its defining quality. The sketch for House of Hope—originally submitted as a conceptual proposal to the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (MOT) in 1996—shows with schematic clarity the house in its totality, as well as its constituent units (fig. 5).20By this time, Montien was well versed in the production of conceptual sketches as a vehicle for the proposal of large-scale installations to international institutions. The structure’s porosity is overshadowed by an impression of impenetrability, as the shape emerges as a dense overlay of precisely drawn lines. This laborious graphic presentation calls attention to the sheer number of beads and stools required to achieve density, perhaps in implicit justification of a financial advance to cover production and shipping costs. The inclusion of a human figure to provide scale is expected, but here, the surrounding elements also function to highlight the installation’s obduracy. A ghostly human silhouette is juxtaposed against, on one side, the house’s solid curtain wall and, on the other side, medicinal beads drawn to real size to solicit the viewer’s literal grasp.21“I want the spectators to use their organs to touch my work, to sense, to be in or near by or far from the artwork. I am interested in creating the work that the very little parts or details, the largest or the whole body of work to present different feelings and perceptions to the spectator.” Montien Boonma, uncatalogued notes, January 20, 1997, MBA.

This schematic clarity, intended to make the work believable for the commissioner, belies the fact that its construction remained untested. For the work’s first staging at MOT in April 1997, Montien relied on the museum’s production team to devise a suspended metal frame from which the beads would hang.22This earlier iteration of House of Hope was shown at Art in Southeast Asia 1997: Glimpses into the Future, Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, April 12–June 1, 1997, and Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, August 2–September 15, 1997. It was only upon arriving in Tokyo that Montien realized that the fabricated frame, overly chunky and in a distractingly bright white, undercut the levitative quality he wanted; worse yet, the work was assigned to a large gallery, leaving plenty of empty space, which negated the intimacy he sought.23Apisit, conversation with the author. As he later recalled, “In Japan, the scent emanates from the work. But for New York, it is as if we have entered a sauna. The work gives an impression of warmth. As soon as you enter the room, herbal aromas surround you. I like the work in New York better. The Japanese version felt too sparse. Ineffective.”24Paisal, “Baan haeng khwam wang khong Montien Boonma,” 38. Despite Montien’s criticism, the Japanese crew could hardly be blamed. After all, the drawing he had submitted prioritized a sense of physical integrity. The team accordingly ensured that the structure, which had to hold the weight of 1,648 strands of hanging beads, was also sturdy enough to be safely entered by visitors, though at the cost of its outsized ponderability.

In the same way that no concept of religion can be relayed without material translation, House of Hope’s making points to the way that there is no such thing as a predetermined shape of experience that can be transported frictionlessly. The invitation to present the work again at Deitch Projects later in 1997 offered Montien the opportunity to propose the wraparound mural, whose spatial illusionism was a deviation from his usual painterly style. In this manner, the freestanding sculptural object dwarfed by the room gave way to a transformation of the room into an immersive enclosure. While this version was successful by comparison to Tokyo, Montien nonetheless equivocated, “I did not let the beads touch the ground in New York. I did not feel good about the cement floor at Deitch Projects.”25Montien, unpublished transcript of interview with Paisal. The coldness of the floor mitigated the warmth that he wished to conjure, a testament to the emphasis Montien placed on calibrating the right interior weather. Indeed, temperature was a recurrent challenge with which the artist contended in his travels; Apisit recalls a project in Scandinavia where Montien asked for his work to be stored in the HVAC room for the heat and humidity to activate the organic pigment—to return the suppleness and chromatic saturation it had in the tropics.26Apisit, conversation with the author. The seeming interchangeability of white cubes belies differentiation across cultural and climatic zones.

This transnational story of House of Hope’s realization is, in many respects, one of an artist at the height of his powers and peak of circulation. Here was Montien ascendant, producing a project of unprecedented scale that fully leveraged the infrastructure of transnational financing, distributed fabrication, and multilingual mediation that constituted the art world. But he was also made keenly aware of the limits of this infrastructure. In an interview given in the fall of 1997—as the Asian financial crisis was in full swing—Montien criticized the installation shots from Deitch Projects with uncharacteristic harshness: “I don’t like them at all. They’re too perspectival. Because the gallery is so small, they had to take the frontal photo from the entryway. It’s a difficult work to photograph.”27Montien, unpublished transcript of interview with Paisal. With the crash of the Thai baht, and with the desertion of the hotels and skyscrapers that once housed Bangkok’s commercial galleries, photographic mediation was the only means that remained for the work’s movement. For all the lubricants and cultural currencies of the art world, the prospects of its showing in Thailand became impossible in the face of real economic illiquidity. Ostensibly a mobile architecture of faith, House of Hope could not travel to where its solace may have been most needed.

If there is a lesson to be learned from the narrative rehearsed here, it concerns the insufficiency of branding Montien’s art as “Buddhist.” The term has been mobilized for interpretations with relish for authenticity and Orientalist stereotype, a far cry from the complex relationship to faith evinced in his approach. This is not simply a retrospective observation, for the postmodern critique was already immanent, with Montien himself a passionate student of continental philosophy. Given his time at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris from 1986 to 1988, it was the legacy of Jean-François Lyotard’s mega-exhibition Les immateriaux (1985) at the Centre Pompidou that plausibly loomed large over his intellectual formation. The show was significant in thematizing global postmodernity as a question concerning communicative technologies that shape a mediated imagination of distant and fragmented cultural “spaces” or “zones.”28Arguably, the show offers a more compelling intertext for his practice—and for much of his contemporaries’ work—than the better-known Magiciens de la terre (1989), with its sociological obsession with national origins and religious authenticity. That Montien had metabolized such semiotic lessons is made clear on a page of undated handwritten notes titled “Postmodern.” He wrote: “Meaning is not communication (information) or signification (symbolism) BUT it is the house where experience lives [sing mi yu asai khong prasopkan], which holds the constant play of difference. The incommensurability of the message is one pathway towards emptiness.”29The passage was written primarily in Thai, with a sprinkling of English words (“message”) and French (“la signification”). Montien, uncatalogued notes, n.d., MBA. Translation mine.

To revisit Montien’s legacy with the question of how discursive structures enable—or stifle—play allows us to see that the biennials, exhibitions, and even the discourse of “contemporary Asian art” in which he figured so prominently were frameworks for the management of cultural difference that made room for the religious but also often accelerated its reification. But these spaces, ungoverned by the norms of orthodox religious architecture, were also critical opportunities for articulating a malleability of faith that need not be beholden to traditional markers of identity. With its resolution for the most nondescript of shapes, House of Hope may be—to take on Montien’s phrasing—a house where difference lives.

House of Hope is currently on view in Gallery 211 at MoMA.

With gratitude for Wong Binghao and Roger Nelson, thoughtful interlocutors; Jumpong Bank Boonma, Apisit Nongbua, and Apinan Poshyananda, generous keepers of memory; Petch Osathanugrah and Poolsri Praepipatmongkol, in memoriam.

- 1See, for instance, Apinan Poshyananda, Montien Boonma: Temple of the Mind, exh. cat. (New York: Asia Society, 2003); and Vishakha N. Desai, “Thailand: Montien Boonma,” ArtAsiaPacific 37 (January 2003): 34.

- 2Mark Stevens, “Belly Up,” New York Magazine, April 24, 2003.

- 3See, for instance, Somporn Rodboon, “Montien Boonma: atalak thongthin su lok sinlapa ruamsamai” [Montien Boonma: From Local Identities to the Contemporary Art World] (lecture, Wat Umong, Chiang Mai, February 25, 2021).

- 4Major exhibitions in Thailand include Death Before Dying: The Return of Montien Boonma, curated by Apinan Poshyananda, National Gallery of Bangkok, February 17–April 20, 2005; [Montien Boonma]: Unbuilt/Rare Works, curated by Gridthiya Gaweewong and Gregory Galligan, Jim Thompson Art Center, Bangkok, April 11–July 31, 2013; Spiritual Ties: A Tribute to Montien Boonma, curated by Somporn Rodboon, The Art Center, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, July 26–September 7, 2013; and Departed <> Revisited, curated by Navin Rawanchaikul, Wat Umong, Chiang Mai, December 26, 2020–March 28, 2021.

- 5As comparative literature scholar Chetana Nagavajara argues: “That he [Montien] was deeply immersed in Buddhism does not require any substantiation. But his interest in Western thinking is worth investigating.” Chetana Nagavajara, “Random Thoughts on Montien Boonma and the Archival Approach to His Life and Work,” Thai Criticism Project, Silpakorn University,July 12, 2013.

- 6Paisal Teerapongwit, “Baan haeng khwam wang khong Montien Boonma” [Montien Boonma’s House of Hope], Seesan, 1997, 36.

- 7Holland Cotter, “ART REVIEW; Immersed in Buddhism and Its Meditation on Paradoxes,” New York Times, February 21, 2003.

- 8Jonathan Goodman, “Focus: Montien Boonma,” Sculpture 22, no. 7 (September 2003): 20–21.

- 9See Paisal, “Baan haeng khwam wang khong Montien Boonma,” 37–38; Montien Boonma, unpublished transcript of interview with Paisal Teerapongwit, 1997, Montien Boonma Archives (hereafter MBA); and Montien Boonma, uncatalogued notes, May 22, 1998, MBA.

- 10Montien Boonma, uncatalogued notes, August 8, 1991, MBA.

- 11These comparisons were not lost on critics in the 1990s. See, for instance, Frances Richard, “Montien Boonma: Deitch Projects,” Artforum 36, no. 6 (February 1998): 91–92.

- 12On an expanded modernist genealogy for this inquiry, see David Joselit, Michelle Kuo, and Amy Sillman, “Shape: A Conversation,” October 172 (Spring 2020): 135–46. On an even more expanded genealogy of shape in relation to Buddhist architecture (and as it relates to Montien, the Buddha’s house), see Kazi Ashraf, The Hermit’s Hut: Architecture and Asceticism in India (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2013).

- 13Joan Kee, “Some Thoughts on the Practice of Oscillation: Works by Suh Do-Ho and Oh Inhwan,” Third Text 17, no. 2 (2003): 141–50.

- 14Apisit Nongbua, conversation with the author, May 9, 2023, in which he recalled how Montien referred to the beads.

- 15As Montien described the oscillatory experience of House of Hope: “From high to low, from low to high, from large to formless, from enclosed to open. The mural gives the impression of a massive landscape, but it is not massive. It is only superficial, only surface.” Paisal, “Baan haeng khwam wang khong Montien Boonma,” 37.

- 16Montien Boonma, “Montien Boonma: Interviewed by Albert Paravi Wongchirachai,” ArtAsiaPacific 2, no. 3 (April 1995): 81.

- 17Montien, “Montien Boonma: Interviewed by Albert Paravi Wongchirachai,” 76.

- 18Montien did not care much for the mutual exclusivity of religions either. He recalled in 1995: “When I was abroad, I found worshipping the Holy Mother by candlelight very special; it feels like she’s looking at you. She answered my prayers too.” Boonma, “Montien Boonma: Interviewed by Albert Paravi Wongchirachai,” 79.

- 19Montien, unpublished transcript of interview with Paisal.

- 20By this time, Montien was well versed in the production of conceptual sketches as a vehicle for the proposal of large-scale installations to international institutions.

- 21“I want the spectators to use their organs to touch my work, to sense, to be in or near by or far from the artwork. I am interested in creating the work that the very little parts or details, the largest or the whole body of work to present different feelings and perceptions to the spectator.” Montien Boonma, uncatalogued notes, January 20, 1997, MBA.

- 22This earlier iteration of House of Hope was shown at Art in Southeast Asia 1997: Glimpses into the Future, Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, April 12–June 1, 1997, and Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, August 2–September 15, 1997.

- 23Apisit, conversation with the author.

- 24Paisal, “Baan haeng khwam wang khong Montien Boonma,” 38.

- 25Montien, unpublished transcript of interview with Paisal.

- 26Apisit, conversation with the author.

- 27Montien, unpublished transcript of interview with Paisal.

- 28Arguably, the show offers a more compelling intertext for his practice—and for much of his contemporaries’ work—than the better-known Magiciens de la terre (1989), with its sociological obsession with national origins and religious authenticity.

- 29The passage was written primarily in Thai, with a sprinkling of English words (“message”) and French (“la signification”). Montien, uncatalogued notes, n.d., MBA. Translation mine.